“Unrebutted Circumstantial Evidence” Leads to Transfer of Dictionary Term Domain Name

There is a price to be paid by not responding to a Complaint. Responding to a legal proceeding, and the UDRP in particular, affords the registrant with the opportunity of putting its facts and arguments before the Panel and rebutting the Complainant’s facts and arguments. One can therefore not expect the same outcome regardless of whether a registrant responds or not.

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 3.39), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with commentary from experts. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ “Unrebutted Circumstantial Evidence” Leads to Transfer of Dictionary Term Domain Name (juvenalia .com *with commentary)

‣ Where is the Line Between Nominative Fair Use and Cybersquatting? (sonicmenuprices .info *with commentary)

‣ Respondent’s Motive in Redirecting to the Complainant’s Website (mit .gay *with commentary)

‣ IBM Faces Embarrassment from Going After a Legitimate Business (ibms .com)

‣ Wait Until the Real Cadillac Finds Out! (adillac .com *with commentary)

—–

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

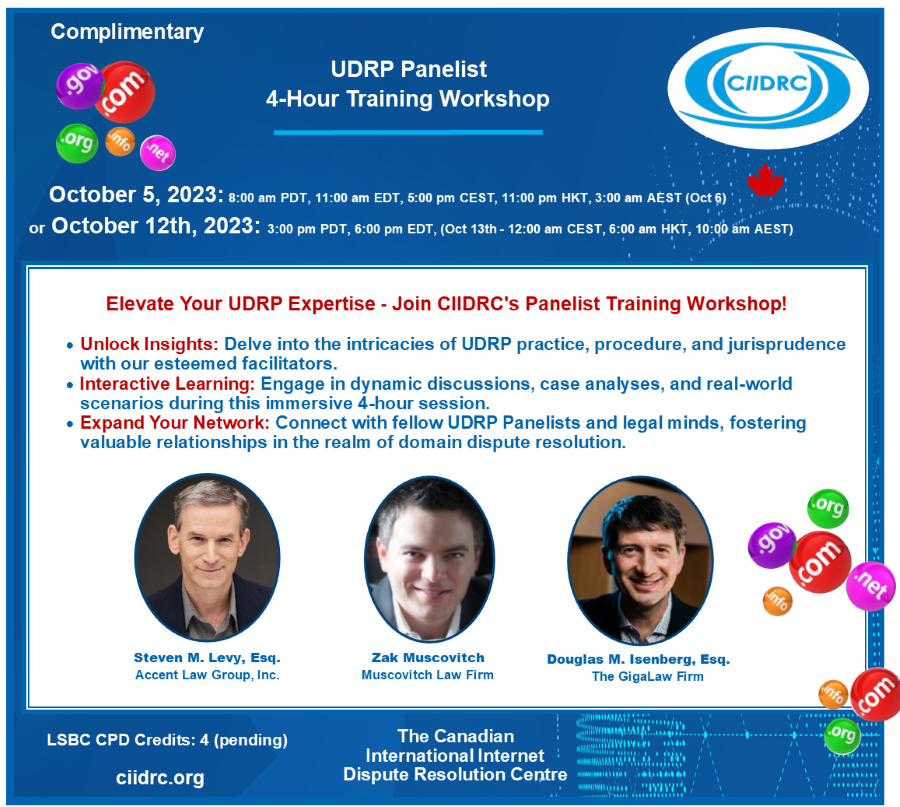

UDRP Workshop registration:

For October 5, 2023 – register here

For October 12, 2023 – register here

“Unrebutted Circumstantial Evidence” Leads to Transfer of Dictionary Term Domain Name

Institución Ferial de Madrid (IFEMA) v. Kwangpyo Kim, Mediablue Inc., WIPO Case No. D2023-2602

<juvenalia .com>

Panelist: Mr. Christopher S. Gibson

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1980, is a consortium which annually organizes and holds exhibitions, trade fairs and shows related to different business sectors where companies meet to generate business relationships and multiply their contacts. The “Juvenalia” event has been organized by the Complainant since the 1980s and the website at <ifema .es> includes web pages dedicated to its JUVENALIA event. The Complainant has provided evidence of a large number of visitors to its website and has also provided evidence to show that it makes significant investments in advertising. The Complainant owns the Spanish trademark registration for JUVENALIA since 1980. The disputed Domain Name was registered on July 21, 2010, and resolves to a pay-per-click parking page that also indicates the Domain Name is for sale.

The Complainant alleges that the website hosted by the Domain Name indicates that it is offered for sale on GoDaddy’s auction site for USD $23,850, a sum far in excess of any out-of-pocket expenses that the Respondent can reasonably be assumed to have incurred in acquiring it. In the amended Complaint, the Complainant points out that the Respondent has already been Respondent in similar cases, in particular: Unilever NV 대 김광표, WIPO Case No. D2002-0614; and Deutsche Lufthansa AG v. Whois Privacy Services Pty Ltd / Mediablue Inc, Kwangpyo Kim, WIPO Case No. D2013-1844. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is in the business of registering domain names and that the Respondent’s non-disclosure of its identity shows that the Respondent has registered and is using the Domain Name in bad faith. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The Panel finds that the Complainant has made a prima facie showing of the Respondent’s lack of rights or legitimate interests in respect of the Domain Name, which has not been rebutted by the Respondent. The Panel also determines that the Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith. The Respondent adopted the term “juvenalia”, identical to the Complainant’s JUVENALIA mark, and the Domain Name was linked to a pay-per-click webpage, while also offering it for sale. The Complainant has provided circumstantial evidence that – given the distinctiveness of its JUVENALIA trademark; the more than 30 years that have passed between Complainant’s earliest trademark registration and the registration of the Domain Name; and the reputation of Complainant’s business while using the JUVENALIA mark for one of its annual events – the Respondent, when registering the Domain Name, was likely aware of Complainant and its JUVENALIA mark, and intentionally targeted it, when registering the Domain Name.

The Panel further finds that the Complainant has provided sufficient unrebutted evidence that the Respondent is using the Domain Name for the bad faith purpose of selling it to the Complainant for an amount that exceeds Respondent’s likely registration costs. The Respondent, by directing the Domain Name to pay-per-click links and also offering it for sale at a high price, has used it in bad faith, see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.1.1. Furthermore, in this case, the Complainant has indicated the presence of additional factors: the Respondent’s use of a privacy service, and the Respondent’s failure as a professional domainer to search and/or screen registrations against available online databases, all of which may be indicia of bad faith. In sum, the unrebutted circumstantial evidence indicates the Respondent is using the Domain Name to take unfair advantage of the Complainant’s JUVENALIA mark.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: PONS IP, Spain

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

There is a price to be paid by not responding to a Complaint. Responding to a legal proceeding, and the UDRP in particular, affords the registrant with the opportunity of putting its facts and arguments before the Panel and rebutting the Complainant’s facts and arguments. One can therefore not expect the same outcome regardless of whether a registrant responds or not. Clearly, responding will generally provide a better chance of the registrant prevailing and will also allow the Panel to benefit from the adversarial system that the UDRP is based upon.

Here, the Respondent failed to respond and he paid the price. Had he responded, the Panel would have had different facts and arguments before it and the outcome may have been different. That being said, it is still possible to critically evaluate the unrebutted facts and arguments made by the Complainant and come to one’s own conclusion as to whether the Panel’s decision was justified in the circumstances.

When you see the word, “Juvenalia”, what do you think? To me it meant nothing and I had never heard of the word prior to this case. That is why I find the Complainant’s conclusory allegation surprising: “Complainant claims that all of its trademarks, including its JUVENALIA mark, have acquired a global and international character”. A children’s festival held in Madrid could perhaps have acquired an “international character” outside of Spain, particularly in neighboring European countries, but I would expect evidence of this. Likewise, for a “global character” as the Complainant alleged, I would expect to see evidence showing that people all over the world have heard of this children’s festival held annually in Madrid, and particularly in Korea where the Respondent resides. From the decision, it looks like the Complainant mainly relied on local posters, traffic to its website from unspecified locations, rankings in search engines which tend to be skewed in favour of the location of the searcher, and advertising expenditures that were likely used in Spain rather than globally. Bottom line, there was apparently no evidence showing that JUVENALIA was an internationally known brand such that someone outside of Madrid or Spain was likely to have heard of it.

The Complainant alleged that “the registration of the trademark JUVENALIA confers on Complainant the exclusive right to use it and to prevent all third parties not having its consent from using it in the course of trade or on communication networks or as a domain name”. We know that’s not the case of course since trademarks are jurisdictional and generally limited to certain goods and services for which the mark is registered for. But perhaps the Complainant left the mistaken impression that JUVENALIA was a coined term that the Madrid government came up with? A Google search from my home in Toronto discloses that in the first hit, a Wikipedia entry explaining that the Juvenalia were games instituted by Nero. If you happen to be up on classics, maybe this term is familiar to you. So, the Complainant did not coin this term but adopted it. Fair enough. Did it mention that there are numerous parties all over the world who use this term or did it portray itself as the exclusive user of a highly distinctive and coined term? My Google search revealed an Irish pop culture podcast using Juvenalia.net, for example.

The Google search also revealed a dictionary meaning of the term in the Merriam-Webster dictionary;

Well down the search results I see a reference to the Complainant’s youth festival in Madrid. I imagine that when searching in Spain, the Complainant is right at the top. Not in Toronto, and I suspect not in Korea where the Respondent resides either. So how is it that the Complainant has its claimed exclusive rights to use this term on the Internet? That question remains unanswered.

With no apparent evidence that the Respondent was actually aware or ought to have been aware of the Complainant, the Complainant alleges that the Respondent ought to have first conducted a trademark search. There is considerable case law establishing that foreign trademark registrations do not put domestic registrants on notice, for example, uwe v. Telepathy, Inc., (Trademark registered only in Germany did not put U.S. respondent on notice of complainant’s mark); and see; Allocation Network v. Gregory, supra (“Complainant has not provided any evidence of facts which might indicate that U.S. Respondent knew or should have known of its [German] trade name use or trademark registrations”). But assuming that there was a higher responsibility to search because the Respondent was a domain name investor as some Panels have found, discovering that the Complainant adopted a dictionary word derived from a classical festival and trademarked it for its particular goods and services, would not necessarily prevent another person from adopting the term as a domain name in good faith since no one company could claim exclusive rights in it, as in Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena S.p.A v. Charles Kirkpatrick, WIPO Case No. D2008-0260.

Similarly, in Delta Dental Plans Association v. Domains By Proxy, LLC / Kwangpyo Kim, WIPO Case No. D2022-0566 (reported and commented upon in Digest Volume 2.24 , the unanimous three-member found that even if the Korean respondent did not have an obligation to conduct a USPTO search, since even if the respondent had conducted one or had conducted a Google search, the respondent could have reasonably concluded that there were plausible non-abusive uses for the domain name. The Panel as a result, found that the Complainant did not discharge its burden of showing bad faith registration.

One aspect of the Delta case which is particularly instructive and relevant to the present Juvenalia case, is the Panel’s comment that in the case of “Delta Life”, the combined term had no obvious meaning and therefore can give rise to an obligation to search. There is merit in this approach. If a Panel sees a term which appears to be or may be a common term or dictionary word, for example, then a Panel could possibly determine that regardless of whether or not the Complainant happened to have a pre-existing corresponding trademark, there is no duty to search because the registrant could comfortably register the term as a domain name without having to conduct a clearance search. On the other hand, when faced with a term that is coined or particularly distinctive, a reasonable registrant would likely first search the term to see if it is solely identified with one particular trader. Even then, a registrant could possibly still register it in good faith absence fame in the mark, as trademark law does not give a monopoly on any term absent sufficient renown.

It is crucial to always bear in mind that the UDRP does not require the transfer of a domain name to a Complainant just because their trademark was registered first. If that were the case, that would greatly simplify the UDRP to a contest of ‘who registered first’. That is, however, not the way the UDRP works or is intended to work. The UDRP requires a specific intent to unfairly target and capitalize off of the Complainant’s mark. That is a big difference from trademark law which does not look at intent but merely who was first. The temptation to side with the trademark registrant just because it was first, must be avoided in favour of carefully determining if there was actual intent to take unfair advantage of a Complainant.

In the Juvenalia case, the Panelist found that that the “Complainant has provided sufficient unrebutted evidence that Respondent is using the Domain Name for the bad faith purpose of selling it to Complainant for an amount that exceeds Respondent’s likely registration costs”. The evidence of this appears to be based on a public GoDaddy auction website and as such there does not appear to be any effort to sell the Domain Name specifically to the Complainant. It is well established that a general offer to the public to sell a domain name corresponding to a dictionary word is not necessarily considered bad faith because it is not targeted at the Complainant (See for example, Allocation Network GmbH v. Steve Gregory, ICANN Case No. D2000-0016). Most recently, in AKAPOL S.A. v. Ehren Schaiberger, WIPO Case No. D2023-2284 (covered in Digest Vol. 3.35), the unanimous three-member Panel found that even in the case of an uncommon or fanciful term that may be of interest to a variety of entities, is not condemned by the Policy unless it is accompanied by some indicia of bad faith. Accordingly, this general offer alone does not prove targeting of the Complainant and it is unclear what other evidence was relied upon.

The Panel apparently relied in part upon use of a privacy service, but it is now well established that in general, the use of a privacy service is not evidence of bad faith (see Mediaset S.p.A. v. Didier Madiba, Fenicius LLC, WIPO Case No. D2011-1954; The use of privacy services in general is not to be objected). It is only when a respondent uses a privacy service primarily in order to hinder legal proceedings, that the use of a privacy service may be an argument supporting an allegation of bad faith.

The Panel also seemed to rely upon the PPC links but there was no evidence that they were targeted in any way to the Complainant, nor are they in Spanish if not accessing the web page from a Spanish country. Today, they appear to me in English and do not related to the Complainant.

There is also the matter of the Complainant alleging that the Respondent has been the subject of previous UDRP cases, and listed three. It is not clear whether the Panel directly relied on this evidence, but interestingly, out of the previous 17 cases filed against the Respondent, 12 were denied, and two of the cases found RDNH against the Complainant.

Ultimately, it was the Respondent’s own fault for not responding as I mentioned at the outset. Nevertheless, it remains a question whether even in the absence of a response, the “unrebutted circumstantial evidence indicates Respondent is using the Domain Name to take unfair advantage of Complainant’s JUVENALIA mark” as the Panel found.

Where is the Line Between Nominative Fair Use and Cybersquatting?

America’s Drive-In Brand Properties, LLC v. Menu man, NAF Claim Number: FA2309002061668

<sonicmenuprices .info>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith

Brief Facts: The US Complainant, founded in the 1950s, operates various franchised chains of drive-in restaurants, including a chain of restaurants specializing in burgers and hot dogs known as SONIC. The Complainant asserts rights in the SONIC mark based upon registration with the USPTO (September 25, 2012). The disputed Domain Name was registered on May 30, 2022 and provides for information about the SONIC items. The Respondent’s Website clearly states it is unofficial and not affiliated with the Complainant, and the Website also contains a clearly marked link to the Complainant’s website at <sonicdrivein .com>.

The Respondent contends that he has created a website at the disputed Domain Name with the primary objective of providing accurate, reliable and up-to-date information about Sonic menu items to the public. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not use the Domain Name for any bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate noncommercial or fair use. Rather the Respondent is misusing the Complainant’s SONIC mark for its own financial gain; this is not an innocent, informational blog; rather the Respondent is impersonating the Complainant for its commercial gain, for example see the recent similar matter of <dunkindonutsprices .com>.

The Respondent further contends that he only uses the portion of the Complainant’s IP necessary to identify the work, namely the Domain Name must include the SONIC mark to identify that the Respondent’s Website offers information on the menu and prices at the Sonic chain of restaurants. The Respondent has placed Google Ads on the Website but that is to generate revenue to cover the costs of paying writers and hosting a website. The Respondent is also willing to make appropriate amendments to satisfy the Complainant if there is any concern that it does not satisfy any appropriate policies, including the removal of the SONIC logo.

Held: The nature of the Respondent’s Website does not imply that the Respondent’s Website is the official website of the Complainant. The Panel accepts that there may be visitors to the Respondent’s Website who arrive under the misapprehension, caused by the presence of the “sonic” element in the Domain Name. However, this is not determinative; the doctrine of nominative fair use accepts a limited degree of consumer confusion in circumstances where the mark is being used in a truthful manner to describe a domain name registrant’s business. Other visitors may be indifferent to the entity operating the Respondent’s Website, as long as it provides accurate information about the Complainant’s menu and prices. Further, the Panel notes that the matter involving the domain name <dunkindonutsprices .com> and an apparently similar fact situation, wherein the Panel found that such conduct did not provide the then respondent with rights or legitimate interests, however in that case the then respondent did not file a response and as such that Panel was entitled to accept all reasonable allegations set forth in the complaint.

Sections 2.5.2 and 2.5.3 of the WIPO Overview 3.0 set out circumstances that panels have considered in determining whether the use of a domain name is fair. In the present case, the Panel is reluctant to find that the Respondent is engaged in the sort of cybersquatting that this Policy is designed to prevent. Specifically, the Respondent’s Website does not hold itself out as anything other than an advertising-supported unofficial website providing information about Sonic’s menu and prices; indeed the Respondent provides both a disclaimer and a link to the official website of the Complainant on the Respondent’s Website. There are no other aspects of the Respondent’s conduct that suggest that the Respondent’s actions are not fair use. In particular, it is not seeking to corner the market in domain names, it has filed a Response in this matter and it is not using fake contact details or engaging in other inappropriate conduct.

Ultimately, the determination of whether the Respondent’s very specific business model provides it with rights or legitimate interest in the Domain Name is dependent on whether or not the Respondent, in operating an unofficial website providing information on the Complainant’s menu, is infringing on the Complainant’s trademark rights in the SONIC mark. This determination relies on complex legal issues around nominative fair use which are more suitable for the courts to decide as opposed to being decided under the Policy. The Policy’s primary purpose is to “combat abusive domain name registrations and not provide a prescriptive code for resolving more complex trademark disputes.” This is not a clear case of cybersquatting. For all of the reasons above, the Complainant has not met its burden of proof in establishing that the Respondent does not have rights or a legitimate interest in the Domain Name.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Jeanette Eriksson of FairWinds Partners LLC, District of Columbia, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

The Complainant restaurant obviously did not appreciate its name being used by a business without its permission. From a brand protection standpoint, this is quite understandable. For instance, the menus may not be kept up to date or customers might have their time wasted by landing upon an unofficial and unsanctioned website. Moreover, what gave the Respondent the right to use the Complainant’s trademark in his domain name? The answer is nominative fair use. There is no way to describe what the website offers other than to employ the name of the restaurant in the domain name. Nevertheless, is the Respondent’s website a genuine information service funded by advertisements, or is it really a ruse dressed up in nominative fair use to drive misdirected traffic for illicit gain? This was a difficult question for the Panel and ultimately the Panel punted in favour of the courts because this issue took the matter outside of the normal parameters of a UDRP which is designed to address clear cut cases of cybersquatting and not more complex, nuanced ones which may involve unresolved questions of law. Nevertheless, “spam blogs” may be a new form of cybersquatting that will eventually be addressed by the UDRP if the case law evolves to determine the appropriate line between nominative fair use and cybersquatting.

Respondent’s Motive in Redirecting to the Complainant’s Website

Massachusetts Institute of Technology v. Malte Brigge, NAF Claim Number: FA2309002060147

<mit .gay>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a university based in Massachusetts, founded in 1859, well known for its study of applied science and engineering. The Complainant has rights in the MIT mark based on registration with the USPTO (registered on October 24, 1989). The disputed Domain Name was registered on September 17, 2022 and redirects to the Complainant’s website at <math .mit .edu>. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name as the Respondent is not commonly known by the Domain Name, nor has the Complainant authorized the Respondent to use the MIT mark. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent does not use the Domain Name for any bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate non-commercial or fair use. The Respondent’s bad faith is evidenced by redirecting the Domain Name to the Complainant’s own website which also indicates actual knowledge of the Complainant’s rights in the MIT mark and intention to cause confusion. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The Respondent has no relationship, affiliation, connection, endorsement or association with the Complainant. WHOIS information can help support a finding that a respondent is not commonly known by the disputed Domain Name, especially where a privacy service has been engaged. The WHOIS lists “Malte Brigge” as registrant of record. Coupled with the Complainant’s unrebutted assertions as to absence of any affiliation or authorization between the parties, the Panel finds that the Respondent is not commonly known by the Domain Name in accordance with Policy ¶ 4(c)(ii). The Domain Name resolves to the Complainant’s Website. The use of a confusingly similar domain name to resolve to a complainant’s website does not constitute a bona fide offering of goods or services or a legitimate noncommercial or fair use as it may provide a false impression that the Respondent is affiliated with or authorized by the Complainant.

The Panel finds that, at the time of registration of the Domain Name on September 17, 2022, the Respondent had actual knowledge of the Complainant’s MIT mark since the disputed Domain Name redirects to the Complainant’s Website. Furthermore, there is no obvious explanation, nor has one been provided, for an entity to register a domain name that contains the MIT mark and use it to redirect visitors to the Complainant’s Website other than to create a false impression that the Respondent is affiliated with or authorized by the Complainant. In the absence of rights or legitimate interests of its own this demonstrates registration in bad faith under Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii). The Panel finds that the Respondent registered and uses the Domain Name in bad faith to create confusion with the Complainant’s MIT Mark for commercial gain by using the confusingly similar Domain Name to resolve to the Complainant’s Website thereby creating a false impression of affiliation. Under Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii), redirecting a disputed Domain Name to a complainant’s own website may still constitute bad faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Jeanette Eriksson of FairWinds Partners LLC, District of Columbia, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Comment by Newsletter Editor, Ankur Raheja: This UDRP matter involving a three-letter domain name registered with a new gTLD, namely .gay. Three-letter acronyms have multiple possible uses and many potential meanings without targeting the Complainant and its trademark, for example see the matters of uwe.com, avk.com and tox.com.

However, here the redirection of the disputed Domain Name to a sub-page at Complainant’s website clearly evinces an awareness of the Complainant and raises suspicion as to the purpose of the domain name registration. Hence, this Panelist interpreted the same as the Respondent having actual knowledge of the Complainant’s MIT trademark and creating a false impression that the Respondent is affiliated with or authorized by the Complainant.

The issue of the MX servers is more interesting and may indicate a more sinister purpose. See below, the status of the active MX Records for the disputed Domain Name, pointing towards Zoho email servers:

Possibly, the domain name registrant was indulging in phishing activities, while he redirected the disputed Domain Name to the official website of the trademark holder, with the aim of giving the impression to the email recipients that the disputed Domain Name is associated and/or owned by the Complainant. This has indeed been modus operandi of many cybersquatters, for example see the matter of TEVA Pharmaceutical Industries Limited v. Privacy service provided by Withheld for Privacy ehf / Oren Harrison, Pacific States Insulation and Acoustical Contracting Inc., WIPO Case No. D2022-1977, wherein it was held:

“The disputed Domain Name does redirect to the Complainant’s website which suggests, falsely, some sort of association or connection with the Complainant. Significantly, the configured MX records pointing to active Gmail accounts indicate that the disputed Domain Name is being used in connection with email communications. These are not authorised by or connected with the Complainant. Given the content of the disputed Domain Name, however, emails from such an account would at the very least misrepresent that the account holder was from, or associated with, the Complainant. That risk of association is reinforced by the redirection of the disputed Domain Name to the Complainant’s website.”

Similar facts were also present in Accuity, Inc. v. Kennith Hunter, WIPO-D2022-0397 (safe-banking.com), as referred in the above decision, except to the fact that the Respondent impersonated the Complainant at the disputed Domain Name itself, instead of applying redirection to the Complainant’s website. Besides, the phishing activity can never confer legitimate interests in the disputed Doman name, see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.13.1 (“Panels have categorically held that the use of a domain name for illegal activity e.g., the sale of counterfeit goods or illegal pharmaceuticals, phishing, distributing malware, unauthorized account access/hacking, impersonation/passing off, or other types of fraud, can never confer rights or legitimate interests on a Respondent.”)

IBM Faces Embarrassment from Going After a Legitimate Business

International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) v. Chait, Mitch, IBMS, WIPO Case No. D2023-2911

<ibms .com>

Panelist: Mr. W. Scott Blackmer

Brief Facts: The US Complainant is operating as “International Business Machines” since 1924, the Complainant has used the initials “IBM” to brand its goods and services since at least 1925. The Complainant has trademark registrations for IBM in numerous countries, including the United States registrations, the earliest dating back to January 29, 1957. The disputed Domain Name was created on December 15, 1998, and WHOIS indicates registrant as the Respondent Mr. Chait of the organization “IBMS”, located at Las Vegas, US and “[***] @greenfence .com” as an email. The Response attaches documents and the declarations (of Mr. Chait and his accountant) showing that IBMS LLC was formed in April 2011 in Delaware (US) and headquartered in Las Vegas, Nevada (US). Mr. Chait is the managing member of IBMS and is also the proprietor of Greenfence, LLC and Greenfence Consumer, LLC. The Complainant alleges that there is no evidence that the Respondent is using the disputed Domain Name for a bona fide offering of goods or services, instead using it illegitimately for fraudulent emails in a phishing scheme.

The Respondent asserts rights and legitimate interests in using its company name for a corresponding domain name, which it was using in connection with the bona fide offering of commercial services until the disputed Domain Name was disabled as a result of the Complainant’s demand to the Registrar. The Respondent also points to the history of this legitimate use of the disputed Domain Name, since the establishment of IBMS as a company in 2011, to support its denial of any intent to exploit the Complainant’s trademark. The Respondent further contends that IBMS is an acronym for “Intelligent Behavior Management System”, and he holds related patents for such a system issued by the USPTO in 2014. The Respondent further contends that there are other organizations also using domain names that legitimately differ by a single letter from “IBM” because of their initials, for example, <ibmc .com>, <ibmi .com>, <ibml .com>, <ibms .us>, and <ibms .org>. The Respondent also denies any involvement in the March 2023 phishing attacks on the Complainant, of which the Respondent was not aware until receiving the Complaint in this proceeding.

Held: The Complainant relies heavily on the argument that the Respondent must have been aware of the world-famous IBM mark and meant to exploit it with a confusingly similar domain name, as evidenced by the March 2023 phishing attacks, and this undercuts the Respondent’s claims to be engaged in a bona fide use of the disputed Domain Name. The Panel finds that the balance of the evidence on the phishing attacks weighs in the Respondent’s favor. It seems improbable that the Respondent registered its company name in 2011 and then acquired a corresponding domain name based on the acronym for its software-based solutions that the Respondent then patented and commercialized, all as part of a scheme to attack the Complainant’s mark by misleading relatively sophisticated potential corporate clients.

The Respondent has further demonstrated its use of the disputed Domain Name for a succession of affiliated businesses for many years until its control of the disputed Domain Name was disabled when this dispute arose. IBMS LLC is clearly not merely a sham company registered to facilitate cybersquatting and trademark exploitation. The company has functioned for more than 12 years and actually holds patents and a registered trademark (for GREENFENCE). This may suffice to establish that the Respondent is “commonly known” by its company name for purposes of the Policy, paragraph 4(c)(ii). Moreover, there are other legitimate businesses and organizations that similarly have initials and the Complainant has not shown that any of the websites associated with the disputed Domain Name imitated, targeted, or competed with the Complainant, or that the disputed Domain Name resulted in actual confusion. The Panel does not find bad faith in the registration and use of the disputed Domain Name on this record. The Panel also concludes that the Respondent prevails on the second element of the Complaint.

RDNH: The Complainant inadequately investigated the underlying facts. The disputed domain name was registered more than 24 years before the Complaint was filed, which should have suggested that some basic research was in order. On balance, the Panel finds that the Complainant’s prosecution of the Complaint was ill conceived and poorly executed but does not represent harassment or bad faith as described in Rule 15(e). Therefore, the Panel declines to enter a finding of RDNH.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Wait Until the Real Cadillac Finds Out!

<adillac .com>

Panelist: Mr. Dawn Osborne

Brief Facts: The Complainant is the owner of the trade mark JEFF WYLER registered, inter alia, in the USA with first use recorded as 1973. The Complainant otherwise claims common law trade mark rights in JEFF WYLER FAIRFIELD CADILLAC having used it since 2001 and using CADILLAC pursuant to a trade mark licence with General Motors. The disputed Domain Name was registered in 2004 and is being used to offer commercial services relating to gift cards. The Complainant alleges that the Domain Name is confusingly similar to the Complainant’s common law trademark JEFF WYLER FAIRFIELD CADILLAC and that the Respondent has registered the Domain Name and a subdomain ‘jeffwylerfairfieldc’ in bad faith to confuse customers that the Respondent is affiliated with the Complainant. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The Complainant is the owner of the trade mark JEFF WYLER registered, inter alia, in the USA with first use recorded as 1973. The Complainant contends that it has common law trademark rights in JEFF WYLER FAIRFIELD CADILLAC explaining that it has had a licence to use the mark CADILLAC from General Motors since 2001. No actual evidence of this licence to use the CADILLAC mark has been presented with the Complaint. Based on the Complainant’s own case if the CADILLAC mark is owned by General Motors and licensed to the Complainant then the Complainant is highly likely not to be the owner of common law rights in the CADILLAC element of any use of JEFF WYLER FAIRFIELD CADILLAC. No rights in CADILLAC as a mark or as an element of a mark is disclosed by the Complaint as presented.

The Panel holds that the disputed Domain Name is not confusingly similar to the Complainant’s JEFF WYLER trade mark or any Rights of the Complainant evidenced by the Complaint. Since the Complainant has failed at the first hurdle it is not necessary to consider the issues of Rights or Legitimate Interests or Registration and Use in Bad Faith. However, the Respondent has not on the evidence provided by the Complainant used a subdomain ‘jeffwylerfairfieldc’ and this subdomain does not, necessarily technically, form part of any registration of the Domain Name by the Respondent. The Complainant has done searches against JeffWylerFairfieldc.adillac and is misrepresenting the meaning of these search results alleging that the Respondent has registered the subdomain ‘jeffwylerfairfieldc’ as part of the Domain Name when it has not.

RDNH: The Complainant is an established business being advised and represented by a law firm. The Complainant has not provided any evidence of Rights sufficient to properly challenge the registration of the Domain Name. It has also misrepresented the meaning of search results to suggest that the Respondent has registered a subdomain containing the Complainant’s JEFF WYLER trade mark when the Respondent has not and it would be impossible to do so.

It is also extremely surprising that the Complainant did not submit any evidence of the actual use being made of the Domain Name, namely commercial services relating to gift cards which do not disclose any targeting of the Complainant by the Respondent. On balance, the Panel believes that by exercising reasonable skill and judgement the Complainant must have realised that its Complaint was bound to fail and that it has not placed all relevant information as to the use of the Domain Name before the Panel. The Panel makes a finding of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Michael A. Marrero of Ulmer & Berne, LLP, Ohio, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: What was the Complainant thinking? That it could get Adillac for itself instead of General Motors? Good for the Panelist in finding RDNH.