Two-Letter Domain Names, the Big Game, and the UDRP, by John Berryhill

John is one of the foremost UDRP defense lawyers having defended hundreds of contested UDRP disputes over 25 years. You can visit his website at https://johnberryhill.com/ and follow him on X at https://x.com/Berryhillj. The views expressed herein are John’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the ICA or its Editors.

As a greater Philadelphia area practitioner, it is worth mentioning that the US held its football championship yesterday (real football, not soccer or that weird thing they do in Australia).

The cost of television advertising during this game averages something like US $8 million for a 30-second spot.

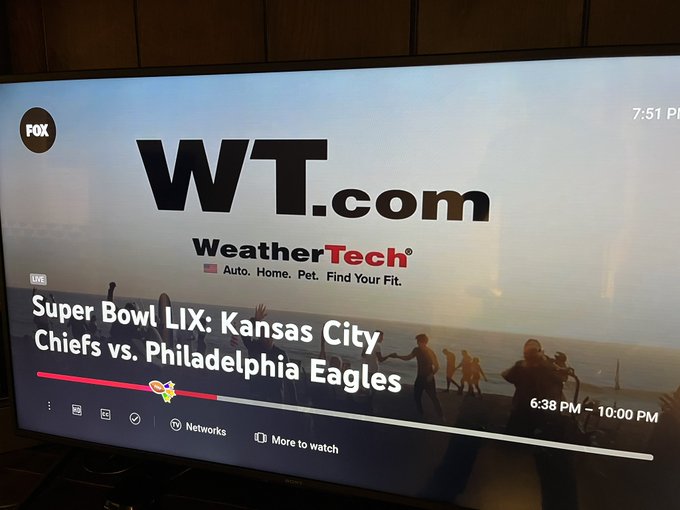

One advertiser chose to use their time to put this domain name in unmistakably large type on the screen:

The domain name is several times larger than their registered trademark or list of custom fit weatherproofing products also shown on the screen.

This company has been around for a while, but it seems they only recently purchased the domain name sometime in 2024.

The price for the domain name was not disclosed, but when last seen, the lander page listed a minimum price of US $3 million.

And this is the thing that has always fascinated me when brand owners want a “reasonable price”. That super bowl ad, with a lifetime of seconds, probably cost them much more than the domain name – which is open for eyeballs all day and night, every day and night.

I used to be fascinated by a pharmaceutical company that had, outside of their facility in New Jersey and facing the New Jersey Turnpike, an enormous stainless steel sculpture of their name. Their name escapes me now, but many years ago, I was settling a dispute with that pharmaceutical company and a domain registrant, and just could not bridge the gap between expectations. Finally, I asked their attorney, “Hey, could you go find out what your client paid for a huge stainless steel sculpture of their name so that random people on the New Jersey Turnpike can read it for no reason at all? Because I will bet you they paid more for that, than what my client is asking for this domain name.”

I don’t know, but if someone wants to spend $8M to get my attention to look at and remember their $3M domain name, then it seems to me the domain name was still a bargain at that price.

There are 47 registered marks in the US in which the textual component consists solely of the letters “WT”. It’s almost surprising that one of them hasn’t attempted a dispute filing of some kind.

The name has been for sale for quite a long time. Its last public WHOIS information suggests it was acquired in 2009. It was originally registered for use by a West Texas oil firm, and even as early as 2007, it was advertised for sale on the page for $500,00.

That span of time until 2024 also demonstrates how much of a waiting game it can be to get an acceptable price. Selling the name for $3M appears to have taken 15 years of saying “no” to anything less. Can a two-letter .com domain name be sold quickly? Sure, but the numbers above suggest it may still have sold low.

But that is what is sometimes on the table in these things, and its almost surprising when a name like this simply sells without having been preceded by a legal action of some kind.

For example, in 1995, Lucky Goldstar changed their name to “LG” when they were still not well known in the US. Thirteen years later in 2008, they decided to pursue in rem suit LG Electronics USA, Inc. v. LG.com (1:08-cv-00672) E.D. Virginia against a registrant who was using it as a “live games” sports score publication site. That case was defended, and ultimately settled.

Also in 2008, Lufthansa filed a UDRP against the registrant of LH.com – which is their flight code prefix, but there is some question as to whether it constituted a mark. The name was registered to a well-known Kuwaiti domaining firm, Future Media Architects, defended by Kenyon and Kenyon. In a 2-1 decision (Marks-Johson presiding, Tatham concurring, Sorkin dissenting), the domain name was ordered transferred, see here. The reasoning was:

“Complainant contends that mass acquisition of two-letter domain names does not demonstrate rights to or legitimate interests in a disputed domain name arising there from and the Panel finds that Respondent lacks rights to or legitimate interests in the <lh.com> domain name pursuant to Policy ¶ 4(a)(ii). …

However, here, Respondent’s business model involves the indiscriminate acquisition and use of as many such domain names as possible.

…

Respondent reported that he had refused an offer of $1,000,000 for the “mark.” The Panel finds that an offer to rent or lease the <lh.com> domain name supports findings of a lack of rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name pursuant to Policy ¶ 4(a)(ii). ”

Ah, yes, the “mass acquisition” of “as many” two letter combinations “as possible.” Given some seven billion people in the world against exactly 676 two-letter combinations in the Latin alphabet, I’d love to know how many of them FMA had at the time.

After the UDRP, FMA did file a UDRP 4(k) lawsuit, and the matter was eventually settled on undisclosed terms.

But, through the magic of saying “no” for long enough, FMA sold the two-letter ai.com domain name for $11 million in 2021.

It also appears that 2008 was something of a turning point for two-letter .com domain names in UDRP disputes:

| Domain | Case | Decision |

| qw.com | WIPO D2024-2516 | Complaint denied |

| kq.com | WIPO D2016-0153 | Complaint denied |

| zt.com | NAF 1660820 | Transferred |

| wi.com | WIPO D2015-1470 | Complaint denied |

| nf.com | WIPO D2015-0706 | Complaint denied |

| yu.com | WIPO D2012-2413 | Complaint denied |

| bs.com | WIPO D2008-1010 | Complaint denied |

| bb.com | WIPO D2008-0389 | Complaint denied with dissenting opinion |

| lh.com | NAF 1153492 | Transfer with dissenting opinion |

| op.com | NAF 1110751 | Transferred |

| xm.com | NAF 861120 | Transferred |

| lv.com | NAF 796276 | Claim Denied |

| rl.com | WIPO D2006-1394 | Complaint denied |

| op.com | WIPO D2004-0899 | Transfer |

Aside from qw.com, which was another illustration of the fact that more identity verification is needed to register a domain name than to file a UDRP, it is breathtaking to compare a decision like LH.com to kq.com. While the panel in LH.com called out domain investing as per se illegitimate, the KQ.com panel notes:

“The Respondent is in the business of buying and selling domain names and assisting others to do so and the fact that the Domain Name is connected to a website offering domain names for sale in no way impacts on the Respondent’s bona fides.”

“The Respondent buys and sells a lot of domain names” made a shift somewhere along the line from being evidence of cybersquatting to being evidence of legitimate rights or lack of bad faith.

Because of the endless creativity of humans in adapting to constraints, lawyers tend to have a natural aversion to bright line rules. But, on the other hand, it is dizzying to watch factual observations such as “the Respondent buys and sells domain names” go from a damning accusation to evidence of an intent not based upon the complainant’s mark.

Another example of this shift from “evidence of cybersquatting” to an affirmative defense is reflected in a pair of surname domain disputes for Fisher.com in 2001 (see here), in which the panel considered

“Complainant also contends that Respondent has a history of registering temporarily lapsed or infringing domain names. […]

Further, Respondent’s only plausible reason for registering the disputed domain name was for the purpose of selling, renting or otherwise transferring it to another, for valuable consideration in excess of Respondent’s out-of-pocket costs directly associated with the disputed domain name.”

…and for Rentsch.com in 2016, in which the panel found (see here):

In this case, the Disputed Domain Name consists of a common German surname “Rentsch” and the pay-per-click links are related to generic job searching websites. Considering this against the background of the Respondent’s apparent business in acquiring and using domain names for business purposes over the years … the Panel considers the Complainant has failed to establish that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the Disputed Domain Name.

Fisher.com was a cybersquatting situation in 2001 because the respondent in that proceeding had a history of acquiring and seeking to profit from surname domains, but Rentsch.com was not cybersquatting in 2016 because the respondent in that proceeding had a history of acquiring and seeking to profit from surname domains.

What a difference a dozen or so years makes.

The last time ICANN had the opportunity to write a domain dispute policy from the ground up was the Uniform Rapid Suspension policy, which applies to new gTLDs. The URS provided an opportunity to codify common domain investing defenses, without prescribing particular outcomes in these types of fact-intensive disputes. For example, the URS states:

5.9 Other factors for the Examiner to consider:

5.9.1 Trading in domain names for profit, and holding a large portfolio of domain names, are of themselves not indicia of bad faith under the URS. Such conduct, however, may be abusive in a given case depending on the circumstances of the dispute. The Examiner must review each case on its merits.

5.9.2 Sale of traffic (i.e. connecting domain names to parking pages and earning click- per-view revenue) does not in and of itself constitute bad faith under the URS.Such conduct, however, may be abusive in a given case depending on the circumstances of the dispute.

These provisions, among others in the URS, focus on some outdated general views of the domain and traffic marketplaces still held by a minority of panelists, while still providing enough flexibility to address circumstances in which trading or monetizing a domain name might be undertaken to the detriment of the complainant’s rights.

It may be worth considering importing these ICANN-consensus-tested dispute provisions into a future revision of the UDRP. Because if a significant component of my net worth were tied up in these things, it would be disquieting to see how the identical rules can lead to opposite conclusions based on the same substantive factors practically defining domain investing in general.

Comments 1

Master level class, thanks.