Fairmont .group – What’s Going on with the Passive Holding Doctrine?

Fairmont Hotel Management L.P. v. Yali, WIPO Case No. D2024-1292

Comment by ICA Director and Domain Name Investor, Nat Cohen:

The Fairmont. Group dispute is more complex and nuanced than it first appears. It raises four questions about how the UDRP is applied.

- Is the passive holding doctrine firmly rooted in the language of the UDRP?

- In a no-response dispute, how is the balance of probabilities determined for the allegation that there is no plausible good faith use for the disputed domain name?

- Does the location of the panelist matter?

- Why is there a recent trend of panelists mischaracterizing the WIPO Overview’s guidance as to passive holding?

The history of UDRP jurisprudence shows that some panelists have attempted, at times successfully, to effectively modify, rewrite, or ignore the actual language of the Policy to expand its scope. UDRP Digest comments on the fuck3cx.com case and the wynncruelty.com case describe how an early UDRP decision succeeded in effectively eliminating “confusing” from the Policy’s requirement that a disputed domain name must be identical or have “confusing similarity” to the Complainant’s mark to satisfy the first element of the Policy. This led to expanding the scope of the Policy to cover domain names that were merely similar rather than confusingly similar.

In another instance, 10-years into the UDRP, a group of panelists threw UDRP jurisprudence into turmoil and encouraged a surge in baseless complaints by pushing what became known as the Theory of Retroactive Bad Faith (RBF). RBF attempted to expand the scope of the Policy to cover domain names that were registered in good faith by eliminating the requirement that registration in bad faith must be demonstrated as an essential element of a decision to transfer a domain name. Fortunately, after several years of disruption, the views of more responsible panelists ultimately prevailed, and RBF was discredited. Yet that the attempt was nearly successful demonstrates again that some panelists (mis)use their discretion to expand the scope of the Policy. This story is told in an article by me and Zak Muscovitch entitled “The Rise and Fall of the UDRP Theory of ‘Retroactive Bad Faith’”.

Yet another instance of panelists attempting to expand the scope of the UDRP was entirely successful. The seminal decision is commonly referred to as Telstra. Telstra declared that under certain circumstances, the scope of the Policy can be expanded by asserting that “non-use” nevertheless can meet the definition of use. This approach is now nearly universally adopted by other panelists and Telstra is one of the most cited of all UDRP decisions.

The premise underlying Telstra is that if it is impossible for the Disputed Domain Name to be put to a good faith use, then its mere registration is in effect presumptive bad faith use. The passive holding doctrine espoused in Telstra is reformulated in the WIPO Overview as “the implausibility of any good faith use to which the domain name may be put”.

Even in the absence of a response, it is the complainant’s obligation to substantiate its allegations with sufficient evidence so that the panel can assess, based on the submitted evidence, whether the complainant’s allegations have met the balance of probabilities standard. In the absence of a robust response, to accurately assess whether there is a plausible good faith use of a disputed domain name would in most cases require a panelist to do outside research as to third-party uses for the relevant term or, alternatively, for a panelist to require that the complainant submit such research themselves in the form of Google searches, LinkedIn searches, trademark searches, etc. that would reveal third-party use, if such use existed.

As noted in the UDRP Digest comments on the fbsolution.info case and on the terravita.shop case, most panelists when dealing with a passively held domain name neither do such research themselves nor require the complainant to provide such research. Panelists usually do not look beyond their own experience and the self-serving submissions of the complainant. Thus, they are prone to errors in judgment as to the implausibility of a good faith use for the disputed domain name. This is demonstrated in the Fairmont .group decision.

The only Fairmont of note in India where the Panelist is located is associated with the Complainant, Fairmont Hotel Management, LP. This can be seen by searching for “Fairmont” on a customized version of Google restricted to India. The first eight results refer to the Complainant. It is therefore understandable why the Panelist expressed “no doubt” and found it “obvious” that Fairmont .group referred to the Complainant and that there was no conceivable good faith use for the domain name.

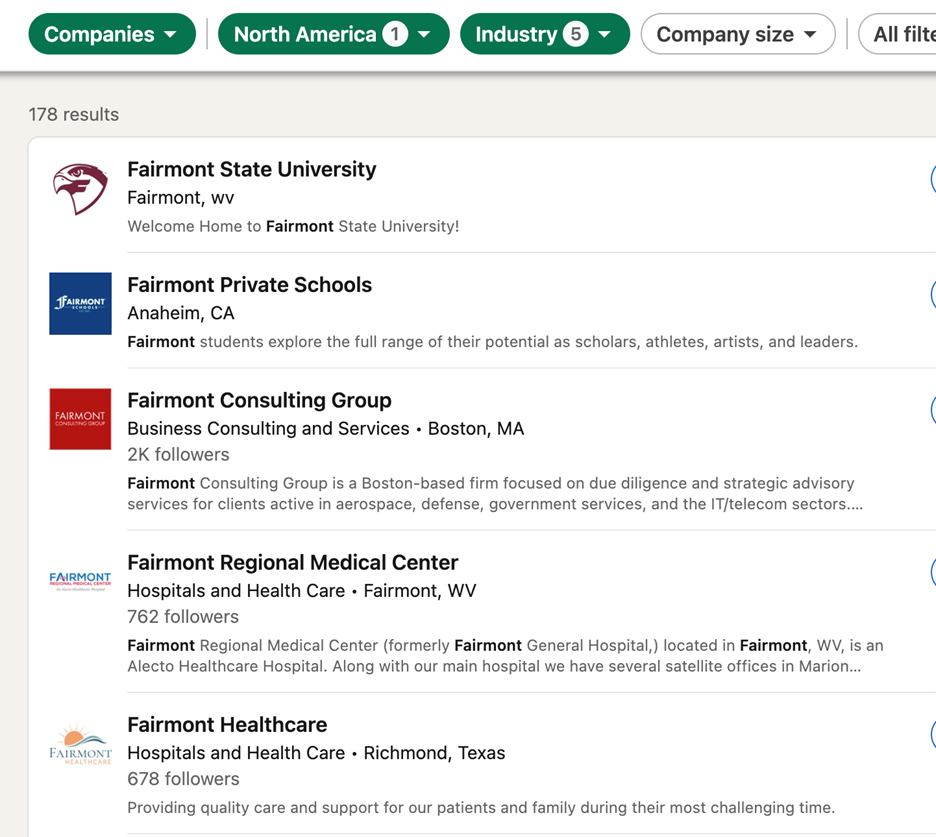

Yet what if the Fairmont .group dispute had been assigned to an experienced North American panelist? The Complainant is the top result for a Google search conducted from the United States, yet the first page of results also includes Fairmont State University, Fairmont Hot Springs Resort, located near Fairmont Hot Springs, Canada and unaffiliated with the Complainant, Fairmont Schools of California, and various web pages associated with the city of Fairmont, West Virginia, and the city of Fairmont, Minnesota. The Wikipedia entry for Fairmont includes numerous places, some businesses, and some schools all named Fairmont, and all located in North America. Searching LinkedIn for organizations in North American named “Fairmont” in just a handful industry sectors, intentionally excluding the Accommodations and Hospitality sectors, returns over one hundred results for organizations named “Fairmont” that are unaffiliated with the Complainant.

A search of the USPTO database for “Fairmont” trademarks returns several active and expired trademarks unrelated to the Complainant.

The answer to the passive holding doctrine’s question as to whether it is possible to conceive of a legitimate use for Fairmont .group unrelated to the Complainant is therefore a resounding, “Yes!”.

A North American panelist, from her own personal experience alone, may very well be familiar with many of these uses for “Fairmont” unrelated to the Complainant. She would thereby be fully aware that the Fairmont .group domain name could be put to many plausible good faith uses that had no connection to the Complainant. Having this awareness, she would recognize that the conditions for the passive holding doctrine were not met and the Complaint must therefore be denied for lack of sufficient evidence of bad faith use. That the dispute was assigned to a Panelist based in India rather than assigned to a panelist based in North America likely contributed to the outcome of the dispute.

This is concerning for several reasons. The outcome of a UDRP dispute should not depend on where the panelist assigned to the dispute is located. Further, transfer decisions should be based on the evidence submitted by the complainant that substantiate its allegations and that can be properly evaluated by panelists – no matter their location. Transfer decisions should not be dependent on a panelist’s prior awareness, or lack of awareness, of certain tidbits of information that happen to be relevant to the dispute. Yet in the Fairmont .group dispute, it was the Panelist’s lack of personal awareness as to the widespread third-party use of “Fairmont” throughout North America that led him to have “no doubt” that the Complainant’s allegations were “obviously” correct and to order the transfer of the Disputed Domain Name. That the geographic location of the Panel may contribute to the outcome of certain disputes also suggests that the selection of the panelist itself can influence the outcome of such disputes.

In the past year, there have been over 350 decisions, including the Fairmont .group decision, which crucially misstate the WIPO Overview guidance on the passive holding doctrine found in section 3.3. All but one of these decisions were issued by WIPO itself. These decisions, written by dozens of different panelists, use identical wording in citing WIPO Overview’s discussion of the passive holding doctrine, but omit the fourth, and critical element of the doctrine.

The language, or some close variation thereof, is –

Panels have found that the non-use of a domain name would not prevent a finding of bad faith under the doctrine of passive holding. Having reviewed the available record, the Panel finds the non-use of the disputed domain name does not prevent a finding of bad faith in the circumstances of this proceeding. Although panelists will look at the totality of the circumstances in each case, factors that have been considered relevant in applying the passive holding doctrine include: (i) the degree of distinctiveness or reputation of the complainant’s mark, (ii) the failure of the respondent to submit a response or to provide any evidence of actual or contemplated good-faith use, and (iii) the respondent’s concealing its identity or use of false contact details (noted to be in breach of its registration agreement). WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.3.

Yet that is not a full statement of what WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.3 says and is notable for what it omits. The crucial factor enumerated in section 3.3, and omitted in the above mischaracterization of section 3.3 is:

and (iv) the implausibility of any good faith use to which the domain name may be put.

This omission has the effect of expanding the scope of the doctrine of passive holding not only to domain names where there is no plausibility of good faith use, such as WellsFargoLogin .net, but to any passively held domain name that is similar to a complainant’s mark, even if the mark is “smile”, “blue”, “crystal”, “sunshine”, or any other common word or phrase. This is a dramatic reformulation of the passive holding doctrine that eliminates the rationale underpinning whatever legitimacy the original version of the passive holding doctrine may claim. It is only the implausibility of any good faith use that could justify treating “non-use” as the equivalent of “bad faith use”. With this limitation removed, there is no justification for treating the passive holding of a domain name susceptible to good faith use as a violation the UDRP’s criterion as to bad faith use.

Remarkably, this mischaracterization of the WIPO Overview is appearing (with but one exception so far) only in decisions issued by WIPO itself. Decisions issued by Forum, CAC and CIIDRC that cite section 3.3 of the WIPO Overview on passive holding cite it accurately.

We are witnessing yet another attempted expansion of the scope of the Policy. Whether this is due to a mistaken citation by one panelist that is being copied by other panelists or whether this is occurring for another reason is unclear. What is clear is that domain names based on terms that are widely used, which are not exclusively associated with the complainant, and which are demonstrably suitable for a good faith use are now more susceptible to transfer because of the recent widespread misapplication of the passive holding doctrine as formulated in Telstra and followed as guiding precedent by most panelists – until now.

It is a principle of physics that force applied in only one direction on an object will cause that object to move in that direction. It is as predictable as a law of physics that the design of the UDRP will over time lead to continuous expansion of the scope of the UDRP – if it is permitted to, as it appears to be.

About the Author: Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.