Are Made-Up Word Registrations Defensible By Respondents?

The issue of investing in ‘brandable’ domain names is a difficult one. As the Panel pointed out, “medaxis” is not a generic word or term, and “has the appearance of a trademark rather than that of a dictionary word or phrase”. Does that mean that it is “off limits” for a domain name investor? (Continue reading here)

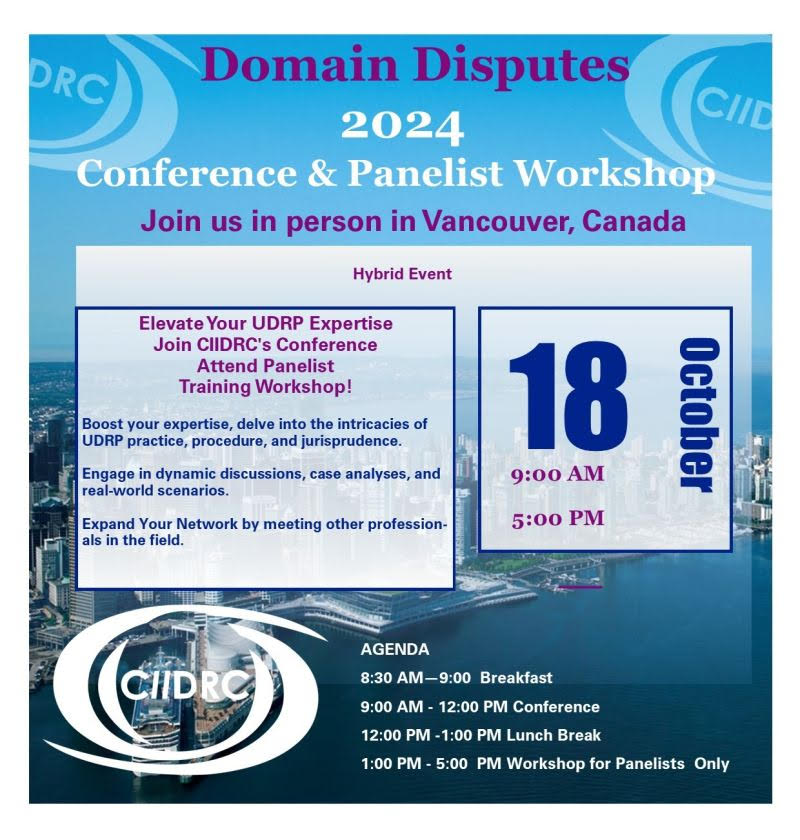

Register today for the CIIDRC’s Domain Disputes 2024: Conference & Panelist Workshop! In-Person in Vancouver, Canada, and Via Zoom.

A series of thought-provoking discussions on hot topics and best practices. The morning will feature sessions that are open to all. They will delve into UDRP statistics with Doug Isenberg, explore the current domain name market with Zak Muscovitch, and gain insights on how to avoid pitfalls in UDRP cases from Steve Levy. Then, Richard Levy and Michael Erdle will discuss refiled complaints, offering valuable perspectives and strategies. The morning will wrap up with Gerald Levine’s presentation, ensuring a rich and informative conclusion to our morning session. We are looking forward to seeing you there! Register here: https://arbitration.vaniac.org/ciidrc-2024-udrp-panelist-training-and-workshop-event-registration/. The afternoon sessions will be open to Panelists only with workshops to be led by Steve Levy, Zak Muscovitch, and Doug Isenberg.

SIGN UP FOR THE CONFERENCE & PANELIST WORKSHOP HERE

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.32), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Are Made-Up Word Registrations Defensible By Respondents? (medaxis .com *with commentary)

‣ Complainant Opts for UDRP After Failed Domain Name Purchase Negotiations (wipsystems .com *with commentary)

‣ Complainant Fails to Provide Evidence Supporting Common Law Rights (authentlc .com *with commentary)

‣ Cadbury Gets Bitter Taste in its Preparation for Success (tayarijeetki .com *with commentary)

‣ Respondent Used Domain Name in Fraudulent Job Application Scheme (fourkite .com *with commentary)

Are Made-Up Word Registrations Defensible By Respondents?

Medaxis AG v. Arash Ansari, WIPO Case No. D2024-2027

<medaxis .com>

Panelist: Mr. John Swinson (Presiding), Ms. Anne-Virginie La Spada and The Hon Neil Brown K.C.

Brief Facts: The Swiss Complainant, founded in 1994, as Ammann-Technik AG, changed its company name to Medaxis AG on October 8, 2002. The Complainant is the owner of several registered trademarks for MEDAXIS including Swiss trademark (January 12, 2001) and International Registration (March 6, 2001), extending to China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom and the United States of America. The Complainant operates a website at <medaxis .ch> and owns other domain names such as <medaxis .fr> that redirect to that website. The Respondent, a Domain Name investor, acquired the disputed Domain Name via an auction of expired domain names, most likely in 2021. The disputed Domain Name redirects to a website titled “BRANDPORTAL” and states “Unleash your business’s full online potential.” A business associated with the Complainant (using email […]@medela.com) contacted the Respondent via GoDaddy in February 2024 and was informed that the Respondent was “looking for” US $42,000 for the disputed Domain Name. In another request by the Complainant via the website at the disputed Domain Name, the Respondent informed the Complainant that the price was US $35,000.

Notably, the Complainant contends that the trademark “Medaxis” is a fanciful term and has no descriptive meaning and is used exclusively by the Complainant. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent took over the disputed Domain Name around the year 2021 to sell it to the Complainant and making a profit knowing that the Complainant had a strong interest in the disputed Domain Name. On the other hand, the Respondent contends that the term ‘MedAxis’ can be seen as a combination of ‘Med’ (a common abbreviation for medical) and ‘Axis’ (a common English word), which could be used in various non-infringing contexts” and that the Respondent had never heard of the Complainant before they reached out and enquired to buy the disputed Domain Name. The Respondent further contends that he acquired the disputed Domain Name in good faith, recognizing its potential value due to its generic and commercially appealing nature and that the Respondent’s willingness to sell the disputed Domain Name is a standard business practice in the domain industry and is not inherently indicative of bad faith.

Held: The Panel acknowledges that, as a general rule, a person such as the respondent has the right to acquire a domain name containing a dictionary word or phrase based upon its dictionary meaning and to offer this for sale at a price of its choosing, provided that in so doing it does not target the trademark value of the term. The Respondent presented no evidence that “medaxis” is a term in any dictionary or used in any publications or the media. In these circumstances, the value of the term “medaxis” in the disputed Domain Name appears to the Panel to derive primarily from the trademark and not from any alleged dictionary meaning. Moreover, the Respondent has presented no evidence to support the Respondent’s submission that he “engages in the legitimate business of domaining”. Merely being a domainer does not of itself ensure that the domainer has rights or legitimate interests in every domain name in the domainer’s portfolio, which is one of the arguments that the Respondent appears to make. Accepting that domaining is of itself a legitimate interest to register any domain name would make the second element of the Policy an empty requirement because it could then be satisfied by merely owning a portfolio of domain names.

In 2021, when the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name, the Complainant held trademark registrations in many countries, and there is no reason to disbelieve the Complainant’s assertion and sample evidence that the Complainant had an Internet presence and reputation in several countries at that time. That said, the mark MEDAXIS is used by the Complainant in relation to relatively niche goods, and the Panel is reluctant to consider that it is generally known to the public. In other words, it is possible that the Respondent was not aware of the Complainant when he acquired the disputed Domain Name at auction. In the present case, based on the facts before the Panel, the Panel takes the view that the Respondent had an obligation to take a least some steps to screen the disputed Domain Name to avoid the registration of a trademark-abusive domain name. This is because the Respondent claims to be a professional domainer and the very construction of the disputed Domain Name stands out as a warning that there is probably a trademark in the background; it looks and sounds like a fanciful and specifically made-up name or brand. The Respondent could have done more to make inquiries but did not do so.

In conclusion, given that the term in the disputed Domain Name has the appearance of a trademark rather than that of a dictionary word or phrase, the Respondent, as a domainer, should have shown a high level of attention and particular diligence when acquiring the disputed Domain Name from an expired domain names auction. In that regard, the Respondent needs to have looked no further than a brief trademark search or a Google search for the trademark owner’s official website. Indeed, one search or the other would more probably than not have disclosed the Complainant’s interest. It seems unlikely to the Panel (although possible) that the Respondent performed no such investigations, but if he did not, then the Panel considers that he should have done so and that his recklessness or willful blindness to the Complainant’s rights does not absolve the Respondent from the consequences of the Policy.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Taylor Wessing Partnerschaftsgessellschaft mbB, Germany

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: The issue of investing in ‘brandable’ domain names is a difficult one. As the Panel pointed out, “medaxis” is not a generic word or term, and “has the appearance of a trademark rather than that of a dictionary word or phrase”. Does that mean that it is “off limits” for a domain name investor?

The value of the term “medaxis” in the disputed domain name appears to the Panel to derive primarily from the trademark and not from any alleged dictionary meaning. As noted in UDRP Perspectives, registering domain names because of their potential value as a ‘brandable domain name’ is nevertheless supported by the Policy. The well-established legitimate interest in aggregating and holding domain names for resale consisting of acronyms, dictionary words, or common phrases can also extend to made-up terms which have no meaning in English but which may in the future be of interest to someone who wants to adopt a new unique brand. Such was the case in Nobli Ltd. v. Cykon Technology Limited, WIPO D2022-2970 <nobli.com>. There, the disputed domain name consisted of a term, “nobli”, that has no meaning in English but the Panel accepted the Respondent’s claim that it registered the disputed domain name because it “may in future be of interest to someone who wanted to adopt a new unique brand”. The Panel went on to say; “As explained in section 2.1 of WIPO Overview 3.0, panels have accepted that aggregating and holding domain names (usually for resale) consisting of acronyms, dictionary words, or common phrases can be bona fide and is not per se illegitimate under the Policy. In the Panel’s view, depending on the circumstances, this practice may also extend to made-up phrases.”

Nevertheless, as the Panel in the case at hand clearly noted, “merely being a domainer does not of itself ensure that the domainer has rights or legitimate interests in every domain name in the domainer’s portfolio”, as if this were the case, then, as the Panel also noted, it would effectively confer a “legitimate interest” to register any domain name by an investor and render the second element of the Policy an empty requirement because it could be satisfied by merely owning a portfolio of domain names.

Yet it is a fundamental precept of trademark law that absent fame in a mark, it is capable of being used by other traders in connection with different goods and services, and potentially even be used for the same goods but in a different jurisdiction. Having a trademark for MEDAXIS then, in theory, should not prevent another company adopting the identical mark for different services or even similar services in a jurisdiction where the Complainant has no trademark rights. And if that is the case, then cannot a domain name investor identify Medaxis .com as a domain name that could be desirable by a third party for reasons that have nothing to do with the Complainant’s trademark and for that reason, register it for resale in the future to just such a third party?

The difficulty with that approach however, is that while it makes good sense in theory and on the basis of the normal confines of trademark law, when it comes to domain name investing there is a strong impetus to defend trademark owners from cybersquatting – even if it means circumscribing what should otherwise, in theory, be a lawful registration. The way this is supposed to be done, is to determine whether the Respondent had the Complainant’s mark in mind when it registered the Domain Name. But where a Complainant’s isn’t sufficiently well known, it often cannot be satisfactorily determined that the Respondent truly did target the Complainant and that the value of the domain name was primarily vested in Complainant’s trademark.

What does a Panel do in such a situation? A Panel would want, of course, to be sure that it was protecting a trademark owner from a cybersquatter masquerading as a domain name investor, but on the other hand, a Panel should not deprive a Respondent of a domain name if the Respondent presents a credible basis for having registered it despite the existence of a trademark.

That question appears to be what the Panel struggled with here; credibility. The Panel inter alia noted that “the Respondent has presented no evidence of any other or how many domain names that he has registered, that he has a practice of only registering domain names that are dictionary terms, or of any other domain names that he has bought or sold…[and] there is no evidence before the Panel to support the Respondent’s submission that he engages in the legitimate business of domaining”. Had the Respondent satisfactorily provided such evidence, the Respondent may have thereby presented a more credible case for having registered the Domain Name in good faith for its value as a made-up term wholly independent of the value as corresponding to the Complainant’s trademark. Where such evidence is credibly presented, Respondents can and do succeed in defending made-up term domain names. Such was the case with, for example, the following cases which are compiled in UDRP Perspectives;

- AKAPOL S.A. v. Ehren Schaiberger, WIPO D2023-2284 <plasticol.com>, 3-member Panel, Denied:

- Venderstorm Ventures GmbH & Co. KG v. Domain Administrator, PTB Media Ltd, WIPO D2024-1287, <babista.com>, 3-member, Denied

- Limble Solutions, Inc. v. Domain Admin, Alter.com, Inc, WIPO D2022-4900, <limble.com>, 3-member Panel, Denied

- Zydus Lifesciences Ltd. (formerly known as Cadila Healthcare Ltd.) v. Jewella Privacy LLC / DNS, Domain Privacy LTD, WIPO D2022-0880, <zydus .com>, 3-member, Denied, RDNH

- Veho Oy Ab v. Jewella Privacy Services, LLC / Domain Manager, Orion Global Assets, WIPO Case No. D2021-4272, <veho.com>, 3-member, Denied

The reason that a Respondent defending a made-up term has a higher onus of demonstrating its bona fides and credibility than in a case involving a dictionary word or acronym, for example, is that it’s just harder to accept that there is value in a made-up term which is independent of a Complainant’s trademark, compared to dictionary words and acronyms. To accept such a contention, a Panel must be persuaded that the Respondent registered the Domain Name for the right reasons and not the wrong reasons as it is usually presumed that it is for the wrong reasons absent evidence to the contrary, in such situations. If it were otherwise, as the Panel suggested in relation to the defense of being a domain name investor, it would just be too easy for Respondents to register a term corresponding to a trademark and claim that it was for reasons that had nothing to do with the Complainant’s trademark.

I think that the best way to look at cases like this is on a ‘continuum’. On one end of the spectrum are cases which involve a common dictionary word and are therefore presumed to have been registered in good faith because of the widespread common generic or descriptive usage of the term. There, the onus is on the Complainant to overcome the presumption of good faith registration. At the other end of the spectrum is a fanciful term, and there the onus is on the Respondent to overcome the presumption of bad faith registration. In the latter case, a Respondent may be able to overcome the presumption by, inter alia, showing a pattern of comparable registrations, by proving its established business model, by explaining the attractiveness of the term via its syntax, components, or suggestiveness, and also by showing that the Complainant is not the exclusive or even predominant user. Where a Complainant is the exclusive or predominant user, like with a famous mark, it will be more difficult for a Respondent to credibly explain its bona fides in registering the domain name.

If, however, a Respondent can show that the Complainant is not particularly known or that there are other companies who all share the same mark, a Respondent may be able to overcome the presumption as since the Respondent can demonstrate that there is value in the term due to is is attractiveness to numerous traders including new entrants to the marketplace, and that the Complainant has no monopoly over the term – much in the same way that a dictionary word registration is often defensible because of its widespread attractiveness and usefulness. It is in relation to this point that I disagree with one of the Panel’s remarks; that “the fact that other businesses also use ‘medaxis’ as a trademark or brand does not assist the Respondent’s argument on this issue”. To the contrary, evidence of third-party usage of a term can be very helpful for the reason aforementioned.

In this dispute, the Respondent failed to present sufficient evidence to support its position that it registered the domain name in good faith due its inherent appeal rather than due to its value as corresponding to the Complainant’s trademark. The Respondent therefore did not overcome the presumption of bad faith registration.

One last friendly word of advice to Panels everywhere: Only domainers should refer to each other as “domainers”. Everyone else should preferably refer to them as “domain name investors”. Although sometimes used colloquially or affectionately, the term does nevertheless carry with it some semblance of belittlement – even if inadvertent – what is otherwise a professional and well-established industry of businesspeople.

Complainant Opts for UDRP After Failed Domain Name Purchase Negotiations

<wipsystems .com>

Panelist: Mr. Terry F. Peppard

Brief Facts: The UK-based Complainant specializing in the provision of software-as-a-service (“SaaS”) cloud-hosted software products for businesses and other organizations and has online presence at the addresses <wipsystems .co .uk> (since 2007) and <wipsystems .com .au> (since 2018). The Complainant alleges that it has held rights in the service mark WIP SYSTEMS for over twenty years but offers no proof for this claim either as to protection under the common law or by dint of its registration with a national or international trademark authority. The Respondent registered the domain name <wipsystems .com> on October 2, 2000, and it currently resolves to a web page labelled “under construction.” The Complainant alleges that the Domain Name has never been employed in connection with an active business enterprise and that the Respondent’s continued inactive holding of the domain name disrupts Complainant’s business.

Between 2003 and 2005, the Complainant attempted to purchase the domain name from the Respondent for US $3,000, but that offer was refused. The Respondent countered Complainant’s offer with a demand for US $10,000, which the Complainant rejected. Between 2004 and June of 2024, the Complainant has made additional attempts to buy the domain name from the Respondent but has received no response to those overtures. The Respondent registered a limited liability company in the US state of Washington in 2017, which registration was administratively dissolved in 2018. The Respondent failed to submit a Response in this proceeding.

Held: In this case, the public record reflects that the Respondent registered the <wipsystems .com> domain name more than twenty-three years ago, on October 2, 2000. For its part, the Complainant concedes that it has held rights in its claimed WIP SYSTEMS service mark “for over twenty years,” but offers no proof for any aspect of this claim either as to protection under the common law or by dint of its registration with any national or international trademark authority. The Complainant’s exceptionally spare Complaint thus leaves open the possibility that the Complainant acquired rights in its claimed mark sometime in the gap between the fall of 2000 and an unidentified date in the succeeding three or more years. In that event, the Respondent’s domain name registration predates Complainant’s rights in the mark. On these facts, we conclude that the Complainant has failed to prove that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith within the meaning of Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii) because the Complainant had no rights to the mark at the moment of domain name registration, or, for that matter, for perhaps three years or more afterward.

The Complainant having failed to carry its burden on the point of bad faith registration of the contested domain name, it is unnecessary for the Panel to consider or decide the remaining issues presented in the Complaint. We therefore decline to examine those issues.

RDNH: In order to justify a finding of RDNH, we must be persuaded both that the Complaint has no merit, and that the Complainant has proceeded under the UDRP in bad faith.

The record demonstrates that the Complainant filed its Complaint in this proceeding out of frustration over a lengthy effort to acquire the challenged domain name through a series of unsuccessful purchase negotiations. Moreover, when it filed its Complaint, the Complainant must have known from available public records that the Respondent had acquired its domain name before the Complainant established, by registration or otherwise, rights in the mark upon which it relies. The Complainant has offered no evidence showing that the Respondent procured its domain name registration in bad faith anticipation of the Complainant’s acquisition of rights in its claimed mark.

On these facts, we find both that the Complaint lacks merit, as detailed above, and that the Complainant’s submissions show that, in filing and prosecuting this proceeding, it has attempted in bad faith to obtain a disputed Domain Name which it has failed to prove is other than the rightful property of the Respondent, as well as that its motivation in pursuing this proceeding was to obtain by abuse of the processes of the Policy what it could not obtain by commercial negotiation. As a result, the Complainant has attempted to commit Reverse Domain Name Hijacking as defined in the Rules.

Complainant Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Martin Saker, Australia

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: It is crucial for Panelist to find RDNH where warranted, as the Panel rightfully did here. It is a key feature of the bargain that is the UDRP: all domains are subject to transfer under the UDRP in order to remedy cybersquatting – but (and it’s a big ‘but’) – the UDRP must not be abused. Where it is abused and RDNH is not found, it calls into question the original fundamental bargain between trademark owners and registrants.

Complainant Fails to Provide Evidence Supporting Common Law Rights

Authentic Brands Group, LLC v. Shipley Marmion, NAF Claim Number: FA2406002104055

<authentlc .com>

Panelist: Mr. Charles A. Kuechenmeister

Brief Facts: The Complainant owns a portfolio of famous brands. It has rights in the AUTHENTIC BRANDS mark based upon its use of that mark in commerce since as early as 2008. The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Name is a typo-squatted version of the Complainant’s mark and that the Respondent is not using the domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services or for a legitimate noncommercial or fair use but instead is using the domain name to send emails impersonating the Complainant to defraud the Complainant and its clients of substantial sums of money. The Respondent also registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith, with actual knowledge of the Complainant’s rights in the AUTHENTIC BRANDS mark. The Respondent did not submit a Response in this proceeding.

Held: The Complainant’s AUTHENTIC BRANDS mark is not a registered trademark, however, it is well-settled that demonstrating common law rights is sufficient to establish rights for the purposes of Policy ¶ 4(a)(i). The Complainant does not expressly assert that it has common law rights in its mark. It alleges that it has operated under the AUTHENTIC BRANDS mark since 2008, but it submitted no evidence to support that. The Complainant submitted the screenshot for it’s website located at <authentic .com>, which advertises the Complainant, listing a number of the brands the Complaint alleges that it represents, and displaying facts about the Complainant also alleged in the Complaint (US $29B+ in annual retail sales, 400K+ points of sale, 150+ countries and the like). Absent, however, is any evidence of the extent of advertising using the mark, and the degree of actual public recognition or association of the mark with the Complainant. The evidence presented falls far short of establishing common law rights in the mark. As the Complainant has failed to satisfy the requirements of Policy ¶ 4(a)(i), the Panel may decline to analyze the other elements of the Policy.

The Panel does note, however, that the evidence submitted in support of the Policy ¶¶ 4(a)(ii) and 4(a)(iii) elements appears to support the Complainant’s allegations concerning those two elements. As to the allegation of use of the domain name to defraud the Complainant and its clients of substantial sums of money, the evidence consists only of a single email purportedly from one of Complainant’s billing managers, from an email account based upon the domain name, demanding payment of an allegedly past-due invoice. A copy of an invoice bearing a bank routing number and customer account number is submitted with the email, but the invoice is payable not to the Complainant but to a well-known clothing distributor. The distributor may well be a client of the Complainant but there is no explanation, let alone evidence, of how the invoice could produce a fraudulent payment. And, this single transaction is the sole support for the Complainant’s allegation of a general fraudulent scheme or practice. The evidence demonstrates passing off or impersonation, but it again falls short of supporting the claim of fraudulent or illegal conduct.

Complaint Denied without Prejudice

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Common law rights are of course permitted by the Policy, but they must be proven through strong and serious evidence as the Panel rightly required here. As noted in UDRP Perspectives:

“For a Panel to award common law rights to any expression, thereby granting it the same status as a registered trademark, without proper evidence would be improper and unjust. To support a claim of common law trademark rights, the Complainant should present strong and serious evidence of constant use by the Complainant and recognition of the trademark from the customers of the associated goods or services.

Proof of common law trademark rights cannot be based on conclusory allegations. A Complainant will have failed to establish common law rights in its mark where it makes mere assertions of such rights, which are insufficient without accompanying evidence to demonstrate that the public identifies a Complainant’s mark exclusively or primarily with a Complainant’s products.”

It is also important to note that the Complaint was dismissed by the Panelist without prejudice. This seems like a good instance for doing so since it affords the Complainant a further opportunity to properly present its case rather than foreclosing the opportunity with a straight dismissal order (which could be tough to overcome without new and previously unavailable evidence).

I would also add, that where a Complainant claims longstanding common law rights but no registered trademark, a Panelist may be curious as to ‘why’ the Complainant has not obtained a trademark registration. In such cases, it may turn out that the Complainant’s application has been denied for some reason and this may be a relevant consideration.

Cadbury Gets Bitter Taste in its Preparation for Success

Cadbury UK Limited v. Amit Akash, WIPO Case No. D2024-2537

<tayarijeetki .com>

Panelist: Mr. W. Scott Blackmer

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a world leader in confectionary products, including chocolates, biscuits, and cocoa-based beverages. These include a malt and dairy beverage marketed since 1920 as a health drink under the brand name BOURNVITA. The Complainant launched a marketing campaign online and in print and other media for BOURNVITA in India beginning in 2011 with the trademarked tagline “tayyari jeet ki” (which, transliterated from Hindi script, may be translated as “preparation for victory or success”). The multimedia campaign was revived in 2013, 2021, and 2022, while the Complainant maintains a website using the tagline <tayyarijeetki .in>, registered in 2021. The Complainant holds the Indian Trademark registrations for TAYYARI JEET KI registered on August 3, 2011, under classes 30 and 32. The disputed Domain Name was created on November 12, 2019. The Complainant discovered in early 2022 that the disputed Domain Name was being used for a website headed “Tayari Jeet ki” with an image of a graduate’s mortarboard and diploma. The website contained information, largely in English, about examination preparation and results for Indian polytechnical colleges.

The Complainant served the Respondent with a cease and desist notice on April 13, 2022, and ultimately reached two individuals associated with the website in July 2023 who apologized for “the trademark violation committed by our company” and stated that they were taking steps to avoid future violations and disabled the website. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent must have been aware of the Complainant’s trademarked and heavily advertised campaign slogan, which had been in use for several years by the time the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name. Thus, the Complainant infers “opportunistic bad-faith”, an intent to mislead Internet users and profit from the “commercial attractiveness” of the Complainant’s mark. In an informal response, the Respondent sent emails to the Center saying that he used the disputed Domain Name for “blogging” for “educational content” and was “open to exploring settlement options” but required compensation for US $6,000.

Held: The Panel finds the Complainant has established a prima facie case that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name. The individuals associated with the Respondent’s former website who replied to the Complainant’s cease-and-desist letter in 2023 apologized for “violating” the Complainant’s trademark and undertook not to repeat such violations, which strongly suggests a lack of rights or legitimate interests. The Panel notes that the disputed Domain Name consists of a Hindi phrase referring to preparation for success, and the Respondent’s former website had content relevant to that phrase, concerning preparation for school exams. As such, the Respondent conceivably might have claimed a legitimate, noncommercial, fair use interest in the disputed Domain Name for its dictionary sense under the Policy, paragraph 4(c)(iii), but the Respondent was no longer using the disputed Domain Name for such a purpose at the relevant time when the UDRP proceeding commenced – nor at present. See WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.11.

The Complainant highlights the “commercial attractiveness” of their trademarked slogan, suggesting bad faith under Policy paragraph 4(b)(iv), which involves intentionally drawing Internet users for commercial gain by causing confusion with the Complainant’s mark. However, this does not align well with the situation here, as the Respondent’s former website did not seem commercial, and the mark is a tagline (“preparation for success”) that could easily relate to both exam preparation content on the Respondent’s former website and the energizing qualities of a malt beverage. Additionally, the record shows that the Complainant registered its mark in 2011 and ran marketing campaigns in 2011 and 2013 and not again until 2021, after the disputed Domain Name was registered, in 2019. The Panel notes that the Complainant did not register a corresponding domain name until November 2021, more than two years after the disputed Domain Name was registered.

On these facts, the Panel cannot find that the Respondent, more likely than not, selected the disputed Domain Name to exploit the fame of the Complainant’s beverage slogan rather than for its plain meaning, which would be appropriate for the sense of preparing for college examinations. The evidence in the case file, as presented, does not indicate that the Respondent’s aim in registering the disputed Domain Name was to profit from or exploit the Complainant’s trademark.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Lall & Sethi Advocates, India

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-representedCase Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: This case demonstrates how important it is for a Panel to carefully consider and analyse the facts rather than finding the way to the easiest outcome. Here, the record disclosed that the Respondent had previously apologized for “the trademark violation committed by our company” and did not formally respond to the Complaint, even asking for USD $6,000.00 as compensation. But the Panelist ended up dismissing the Complaint after carefully weighing the evidence and finding inter alia, that the Complainant’s mark was not actually all that well known at the time of the domain name registration and that the Respondent’s previous website appeared to be genuine and unrelated to the Complainant. As such, the Panel prudently found that it “cannot find that the Respondent, more likely than not, selected the disputed domain name to exploit the fame of the Complainant’s beverage slogan rather than for its plain meaning, which would be appropriate for the sense of preparing for college examinations”.

Respondent Used Domain Name in Fraudulent Job Application Scheme

FourKites Inc. v. Damien CURTIS, HANSKED, INC., WIPO Case No. D2024-2364

<fourkite .com>

Panelist: Mr. Harrie R. Samaras

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a supply chain visibility company founded in 2013 with offices in the United States and abroad (e.g., Netherlands, Germany, India, Singapore). It owns U.S. Registration for FOURKITES (registered September 9, 2014). Since its inception, the Complainant has used the trademark in connection with its products and services in the United States and internationally. The disputed Domain Name was registered on May 29, 2024, and currently does not resolve to an active website. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has been using the disputed Domain Name in a fraudulent scheme that includes posting fake job openings to solicit applicants for positions advertised as if they were with the Complainant. When an applicant submits an inquiry on the Internet about the job posting, an email is sent to the applicant inviting them to participate in an “electronic interview”.

When the applicant confirms their interest, the Respondent sends the applicant a “Screening test/Interview questions” document, followed by a purported “Employment Offer Letter”. Thereafter, the Respondent will solicit additional sensitive information from the applicant, such as the applicant’s signature, driver’s license photograph and related information on the front and back of the applicant’s driver’s license, and applicant’s financial accounts (for direct deposit or wire transfer). At each step in the process, when the Respondent sends emails to the applicants, the Respondent uses an email originating from the Domain Name to appear to the applicants that the email is originating from the Complainant (i.e., [name]@fourkite.com] and letters are also made to look like it originated from the Complainant, using the Complainant’s mark, logo, and one of its mailing addresses.

Held: Having reviewed the available record, the Panel finds that the Complainant has established a prima facie case that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name. The Panels have held that the use of a domain name for illegal activity here, the creation of a false and misleading association between the Respondent and the Complainant in an attempt to impersonate the Complainant and profit from such conduct, can never confer rights or legitimate interests on a Respondent.

In the present case, the Panel notes that the Respondent registered a confusingly similar Domain Name in which it has no rights or legitimate interests at least 10 years after the Complainant began using the trademark. Since the inception of the Complainant, it has used the mark internationally including in the United States. Furthermore, the Domain Name incorporates the mark in its entirety except for eliminating the last letter in the mark – the letter “s”. This evidence makes it more likely than not that the Respondent knew of the Complainant and its rights in the mark when registering the disputed Domain Name. Moreover, the fraudulent scheme that the Respondent has been perpetuating with the Domain Name further evidences Respondent’s bad-faith registration. For all of these reasons, the Panel concludes that the Respondent registered the Domain Name in bad faith.

Further, the Respondent’s bad faith use of the trademark is evident from the fraudulent scheme that appears to be aimed at getting sensitive, personal information from applicants which may ultimately lead to gaining access to the applicant’s financial accounts, thus profiting financially from the scheme. The Panels have held that the use of a Domain Name for illegal activity, the fraudulent scheme described above, constitutes bad faith. The fact that the Respondent is not currently using the Domain Name in conjunction with a website is inconsequential as the Respondent is using the confusingly similar Domain Name in which it has no rights or legitimate interests and the trademark to perpetrate fraudulent scheme and, could, in the future, use a website for similar purposes.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Polsinelli PC Law firm, U.S

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by Newsletter Editor, Ankur Raheja: Indeed, the use of the disputed Domain Name in an illegal activity can never confer rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name and is emblematic of the Respondent’s bad faith registration and use of the disputed Domain Name. See: Day & Zimmermann, Inc. v. Contact Privacy Inc. Customer 12410536882 / Name Redacted, WIPO Case No. D2021-3406:

The Respondent used the Disputed Domain Name to impersonate an employee of the Complainant and perpetrate a phishing scheme directed against several of the Complainant’s job applicants, a strong indication of bad faith. The Respondent’s phishing scheme to send fraudulent emails purporting to come from the Complainant or the Complainant’s employee seeking sensitive personal and financial information from unsuspecting job applicants evidences a clear intent to disrupt the Complainant’s business, deceive individuals, and trade off the Complainant’s goodwill by creating an unauthorized association between the Respondent and the Complainant’s YOH Mark. See Banco Bradesco S.A. v. Fernando Camacho Bohm, WIPO Case No. D2010-1552. Such conduct is emblematic of the Respondent’s bad faith registration and use of the Disputed Domain Name.

Also see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.13.1 and WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.4.