Finding Bad Faith Despite Lack of Evidence

In this case, a Domain Name that predates the Complainant’s registered trademark rights dropped and then was registered by a third-party. It apparently was never developed as it is currently on a default GoDaddy landing page.

While there may be more evidence of bad faith use in the case file available to the Panel than that disclosed in the decision, the evidence for bad faith relied upon in the decision appears to be insufficient to justify a finding of bad faith. Further, the current use of the domain name, and the apparent use of the domain name prior to the commencement of the decision according to Archive.org, were both for a standard GoDaddy landing page that would not support the allegations of bad faith use made by the Complainant. This case is therefore notable because it demonstrates how a Panelist can make a finding of bad faith registration and use despite a lack of evidence. Read commentary here.

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 5.9) as we review these noteworthy recent decisions with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Finding Bad Faith Despite Lack of Evidence (feberg .com *with commentary)

‣ Lawyer Unable to Show His Surname Acquired Distinctiveness as an Unregistered Mark (nativwiniarsky .com *with commentary)

‣ Panel: Common Word Domain Name Can be Legitimately Used for Different Purposes Unrelated to the Complainant (gopa .com *with commentary)

‣ Material Time for Proving Common Law Trademark Rights is Before Domain Name Registration (tigeraesthetics .com *with commentary)

‣ Respondent’s Willingness to Sell the Legitimately Owned Domain Name (hydacservice .com *with commentary)

Finding Bad Faith Despite Lack of Evidence

<feberg .com>

Panelist: Ms. Nayiri Boghossian

Brief Facts: The Complainant sells automotive replacement headlights mostly online and owns a US Trademark for FEBERG registered on September 29, 2020. The disputed Domain Name was registered on July 30, 2021, and resolves to a parking page with PPC links. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is not using the disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services and that the Respondent must have had knowledge of the Complainant’s trademark, which was registered prior to the registration of the disputed Domain Name. The Complainant further alleges that the disputed Domain Name resolves to a parking page containing PPC links for commercial establishments. Non-use or passive use does not prevent a finding of bad faith under certain circumstances. The Complainant further adds that it attempted to contact the Respondent, but the latter did not reply. The Respondent did not reply to the Complainant’s contentions.

Held: Having reviewed the available record, the Panel finds the Complainant has established a prima facie case that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name. The Respondent has not rebutted the Complainant’s prima facie showing and has not come forward with any relevant evidence demonstrating rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name, such as those enumerated in the Policy or otherwise. The Panel further notes that the disputed Domain Name incorporates the Complainant’s registered trademark in its entirety and the disputed Domain Name was created after the registration of the Complainant’s trademark. Therefore, the Panel finds that the Respondent knew or should have known of the Complainant at the time of registration of the disputed Domain Name (see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.2.2).

Paragraph 4(b) of the Policy sets out a list of non-exhaustive circumstances that may indicate that a domain name was registered and used in bad faith, but other circumstances may be relevant in assessing whether a respondent’s registration and use of a domain name is in bad faith. WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.2.1. The Panel finds that by using the disputed Domain Name for a parking website with PPC links, the Respondent has intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to its websites or other online location by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s mark. Such use constitutes bad faith pursuant to paragraph 4(b)(iv) of the Policy. The Panel finds that the Complainant has established the third element of the Policy.

Transfer

Complainant’s Counsel: Chenlu Zhu, China

Respondent’s Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by Nat Cohen, ICA Director:

Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

In this case, a Domain Name that predates the Complainant’s registered trademark rights dropped and then was registered by a third-party. It apparently was never developed as it is currently on a default GoDaddy landing page.

While there may be more evidence of bad faith use in the case file available to the Panel than that disclosed in the decision, the evidence for bad faith relied upon in the decision appears to be insufficient to justify a finding of bad faith. Further, the current use of the domain name, and the apparent use of the domain name prior to the commencement of the decision according to Archive.org, were both for a standard GoDaddy landing page that would not support the allegations of bad faith use made by the Complainant. This case is therefore notable because it demonstrates how a Panelist can make a finding of bad faith registration and use despite a lack of evidence.

As a point of clarification, while at times Complainants and Panels will rely upon the Telstra doctrine to make a finding of bad faith even when a Disputed Domain Name is passively held and the only use is by the registrar for a default registrar landing page, as here, in this dispute the Panel does not mention Telstra, nor would Telstra be applicable as there are conceivable good faith uses for the Domain Name.

FEBERG is a bicycle light manufacturer from China. FEBERG was registered as a trademark with the USPTO in September 2020. The Disputed Domain Name, Feberg .com was first registered in 2017, apparently to someone in Poland. The Domain Name was then registered to the Respondent in July 2021. The Respondent did not Respond, perhaps, as the Panel noted, because the Respondent is in the Ukraine and there is a war going on there.

Non-targeted PPC links are claimed by the Complainant, as follows:

“The disputed Domain Name resolves to a parking page containing PPC links for commercial establishments.”

The domain appears to be on a generic GoDaddy landing page with no PPC links-

It is not clear whether the Complainant’s characterization of “PPC links to commercial establishments” refers to links on the GoDaddy landing page promoting GoDaddy’s own services, which would not be paid links, or whether this characterization refers to some other page that is no longer publicly accessible. In any case, the Complainant does not allege that the PPC links are targeted to the Complainant’s products or services, nor that the Respondent is enjoying any financial benefit from such links.

Archive.org shows that in December 2024, prior to the commencement of the dispute, feberg.com was going to the same URL as it is now, so it seems likely that the Complainant may be relying on a generic GoDaddy landing page as evidence of bad faith use.

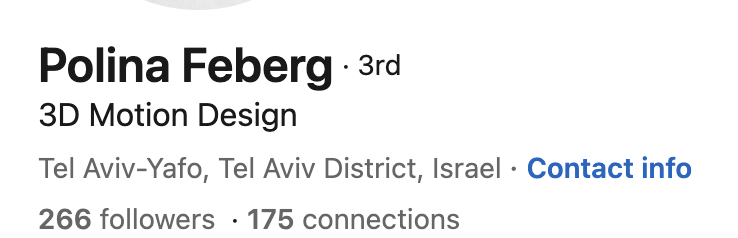

If the term FEBERG were uniquely associated with the Complainant, then under the Telstra doctrine perhaps the Panel could make a finding that there could be no possible good faith use for the feberg .com domain name. Again, as noted above, neither the Complainant nor the Panel is relying on the passive holding doctrine, as bad faith use in the form of PPC links was alleged. Yet it may be worth addressing for a moment the question, “Even in the absence of any evidence of bad faith use, might the passive holding doctrine apply”? The answer apparently is that it would not. While a Google search on Feberg predominantly shows the Complainant, there are other possible good faith users, such as a few people with that last name, for example:

That the domain name was first registered in 2017 and that the Complainant was not able to secure the exact match .com domain name of its brand when it first developed the brand because the domain name predates the development of the brand, suggests that the Domain Name has appeal beyond the Complainant and also demonstrates that the original registrant conceived of a use for the feberg .com domain name unrelated to the Complainant’s use.

The bad faith section of the decision is quite short. It is worthwhile considering it in full. I’ve copied it below, along with some of my own comments interspersed.

Bad Faith section – Annotated

From the Decision:

“The Panel notes that, for the purposes of paragraph 4(a)(iii) of the Policy, paragraph 4(b) of the Policy establishes circumstances, in particular, but without limitation, that, if found by the Panel to be present, shall be evidence of the registration and use of a domain name in bad faith. In the present case, the Panel notes that the disputed domain name incorporates the Complainant’s registered trademark in its entirety and the disputed domain name was created after the registration of the Complainant’s trademark. Therefore, the Panel finds that the Respondent knew or should have known of the Complainant at the time of registration of the disputed domain name. WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.2.2.”

Comment: The Panel here relies on Constructive Notice

From the Decision:

“Paragraph 4(b) of the Policy sets out a list of non-exhaustive circumstances that may indicate that a domain name was registered and used in bad faith, but other circumstances may be relevant in assessing whether a respondent’s registration and use of a domain name is in bad faith. WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.2.1.”

Comment: The UDRP gives a Panel wide discretion to make a finding of bad faith based upon the circumstances.

From the Decision:

“The Panel finds that by using the disputed domain name for a parking website with PPC links, the Respondent has intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to its websites or other online location by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s mark. Such use constitutes bad faith pursuant to paragraph 4(b)(iv) of the Policy.”

Comment: As discussed above, either the Panel is relying on a default GoDaddy lander with links to GoDaddy services as evidence of bad faith, or there is another web page we do not have the benefit of seeing that contained non-targeted PPC links. If the latter case, such PPC links are apparently not targeted to the Complainant’s products or services or those of its competitors. It appears that the Panel found bad faith either based on the default GoDaddy landing page that merely promoted GoDaddy’s own services (which seems most likely as it is the current and past usage), or the Panel found bad faith because of the use for an unknown webpage that had non-targeted PPC links.

Neither possibility would provide sufficient evidence of bad faith use directed towards the Complainant. Yet the Panel nevertheless made a finding of bad faith registration and use.

Implications

Shouldn’t the Policy, intended to combat instances of cybersquatting, have more specific requirements when it comes to bad faith in order to avoid such findings of bad faith in the absence of sufficient actual evidence? It is concering that a Panel could find bad faith and order the transfer of a domain name, such as feberg .com, apparently on the basis of it going to a GoDaddy landing page or on the basis of a general PPC page without evidence that the Respondent actually targeted or had the Complainant in mind in its registration and use of the domain name.

The UDRP could benefit from some codification of circumstances that qualify as bad faith embedded into the Policy itself. Even attempts to provide outside guidance on the circumstances where a finding of bad faith is appropriate, like that offered by the WIPO Consensus View and by UDRP Perspectives, while helpful, are outside of the Policy and in no way limit the very broad discretion of Panels to find bad faith regardless of the circumstances.

Lawyer Unable to Show His Surname Acquired Distinctiveness as an Unregistered Mark

Nativ Winiarsky v. Todd Bank, Todd Bank, WIPO Case No. D2025-0047

<nativwiniarsky .com>

Panelist: Mr. W. Scott Blackmer

Brief Facts: The Complainant is an attorney in New York City, United States, practicing law since 1996, currently as a named partner in the law firm of Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens, LLP. The firm operates a website at <kuckermarino .com>. The Complainant has no registered trademark but claims common law rights in his personal name as a “Trademark” associated with his professional services in the field of real estate law. The Complainant cites his authorship of legal articles and mentions it in news articles and podcasts, which are documented in the record. The disputed Domain Name was created on September 7, 2023, and is registered to the Respondent, who is a New York lawyer representing plaintiffs in class actions. The disputed Domain Name resolves to a single-page website concerning the criticism of the Complainant headed with this sentence: “Nativ Winiarsky is a Sleazy Lawyer Who Gets Disciplined and Sanctioned and Loses Cases… Welcome to this non-defamatory website!”

The Complainant also attaches the civil complaint for defamation mentioned on the Respondent’s criticism website. That complaint seeks an injunction to remove defamatory statements from the Respondent’s criticism website and from any other online sites, as well as from search engines. The New York judicial proceeding evidently is pending at the time of this Decision. The Respondent contends that the Complainant has not established common law trademark rights in his personal name, as he does not provide his services independently of the law firm Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens, LLP. The Respondent observes that the Complainant advertises his services only on his law firm website, and there is no evidence that the Complainant enters into contracts or receives payments for legal services in the name of “Nativ Winiarsky” rather than in the name of his law firm. The Respondent cites Joseph Leccese v. Crystal Cox, WIPO Case No. D2011-0679.

Preliminary Matter – Privacy Redaction: The Respondent requests the redaction of his name in this Decision in the interests of preserving his privacy. The Rules and Supplemental Rules do not offer guidance on the redaction of party names for privacy purposes, but this is sometimes done in published decisions when a party offers a compelling reason. The Respondent has not suggested such a reason in this instance. The Respondent is a licensed New York lawyer advertising his services online in his name on his professional website. The Panel also notes that the parties’ names have already become a matter of public record in the pending civil litigation between them. Hence, the Panel finds no compelling reason to withhold the Respondent’s name in the published Decision in this proceeding and denies the Respondent’s request for redaction.

Held: It is well accepted that the first element functions primarily as a standing requirement. “In situations… where a personal name is being used as a trademark-like identifier in trade or commerce, the complainant may be able to establish unregistered or common law rights in that name for purposes of standing to file a UDRP case where the name in question is used in commerce as a distinctive identifier of the complainant’s goods or services.” WIPO Overview 3.0, section 1.5.2. The Complainant here points to his practicing law since 1996, serving as a named partner in his law firm with a page devoted to his practice on the law firm website, authoring articles in professional publications, and appearing in media articles and podcasts. Many of these facts are similar to those in the Joseph Leccese decision cited by the Respondent. However, what distinguishes the facts in the current proceeding from these cited cases is that the Complainant’s surname, Winiarsky, does indeed appears in the name of the law firm that serves as the platform through which he provides legal services.

This was not the case as early as 1996, but that public database shows that the law firm added the Complainant’s surname to the name of the partnership in April 2019. The Panel is unable however to find, on this record, that the Complainant’s surname by itself has acquired distinctiveness as an unregistered mark for the purposes of the Policy. The Complainant only appears to do business under the firm name, which includes his surname only as part of the longer name Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens LLP, as shown on the firm’s website and printed brochure. The firm uses a domain name based on the first two names, “Kucker Marino” and sometimes displays the firm name without the “LLP” designation and sometimes uses a logo with the initials “KMWB” arranged around a plus sign. But there is no real evidence in the record or on the website of the Complainant’s firm that the Complainant’s services are advertised and sold under the Complainant’s name alone or that the Complainant’s name is recognized by a relevant market as a service mark for the Complainant law firm.

RDNH: The Complainant, a lawyer represented by legal counsel, failed adequately to establish common law trademark rights and seems to have confused the elements of a UDRP complaint with those of the tort of defamation. The Complainant failed to address the Respondent’s predictable claim to be making nominative fair use of the disputed Domain Name for a criticism website until making a belated attempt to brief the issue in a supplemental filing. The Panel does not find RDNH, however, because some complainants have successfully proven trademark use of their personal names, and when the Complaint was initially filed, the Respondent’s identity was not known; he entered an appearance in the civil suit for defamation only on February 2, 2015.

When the Complaint was filed, it could not be known, for example, whether the Respondent was actually a competitor and using the criticism site as a pretext to gain commercial advantage. The Complainant’s arguments have not been well-conceived or executed, but it was not outside the realm of possibility that the Complainant could seek relief under the Policy, given the composition of the disputed Domain Name and the allegation that the criticism site was defamatory. The Panel does not find, therefore, that the Complainant brought the Complaint in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking or to harass the domain-name holder.

Complaint Denied

Complainant’s Counsel: Kane Kessler, PC, United States

Respondent’s Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: As lawyers, we will naturally have some sympathy for another lawyer whose name becomes the subject of a critical and allegedly defamatory website. On the other hand, we may also recognize that freedom of speech within the bounds of the law must be protected, especially where it is in the public interest by bringing serious issues to the attention of the public. Here, the Panel dismissed the case because the Complainant had not proven that “the Complainant’s surname by itself has acquired distinctiveness as an unregistered mark for the purposes of the Policy”.

Should we be concerned that the UDRP deprived the Complainant of recourse? Not at all. The Complainant already has a pending court action for defamation and injunctive relief where the Complainant may prevail and obtain the recourse that the UDRP did not offer in the circumstances. As is said repeatedly, the UDRP is not intended to resolve all kinds of disputes (UDRP Perspectives at 0.1). Rather, it is only designed and intended for clear cut cases of cybersquatting. Other disputes are not intended to be resolved by the expedited and administrative nature of the UDRP procedure. Where as here, the UDRP cannot offer a remedy because the specific criterion have not been met, courts remain available and therefor the Complainant may pursue its grievances there, with a more robust, established, and comprehensive legal regime available.

Even if the Complainant had met the first prong of the three-part test in this case, a Panel might conclude that this was not the type of case that the UDRP was meant to address, regardless of claims of defamation etc. As noted in UDRP Perspectives at 2.10, it is immaterial what the Panelist may think of the quality, utility or lawfulness of a critical website, e.g. whether it may be scandalous, not worth protecting, or defamatory since such issues are beyond the scope of the UDRP.

A final note about the other noteworthy aspect of this decision. The Panel set out what may be a very simple but concise rule for when a Respondent’s name should be redacted: “a compelling reason” (“The Panel finds no compelling reason to withhold the Respondent’s name in the published Decision in this proceeding and denies the Respondent’s request for redaction”). That seems to me to be an appropriate general rule of application that leaves sufficient room for determining what is fair in the circumstances, though we would all benefit from a more detailed set of circumstances that have constituted “a compelling reason” in previous cases so that we may better apply the rule in future cases.

Panel: Common Word Domain Name Can be Legitimately Used for Different Purposes Unrelated to the Complainant

<gopa .com>

Panelists: Mr. Assen Alexiev (Presiding), Mr. Jeremy Speres and The Hon Neil Brown KC

Brief Facts: The Complainant, established in 1965, is the parent company of the GOPA Consulting Group, a multidisciplinary group of consulting and engineering companies. The Complainant is the owner of a number of trademark registrations for “GOPA”, including the European Union trademarks (registered on July 21, 2009 and July 28, 2009) and an International trademark (registered on February 4, 2021). The Complainant is also the owner of a number of domain names, the earliest of which is <gopam .de>, registered on January 1, 2000 and further registrations of <gopa .eu>, <gopa-group .eu>, and <gopa-group .com> in 2006. The disputed Domain Name was registered on April 15, 2007 and invites purchase bids for it with a minimum price of US $25,000. The Respondent contends that it did not know of the Complainant in 2007, when it acquired the disputed Domain Name, and notes that the Complainant’s first trademark application in the United States was filed only in 2021.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent’s registration of the disputed Domain Name in 2007, shortly after the Complainant began registering and using domain names containing “GOPA” in 2006, prima facie establishes that the registration was made to sell the disputed Domain Name to the Complainant, who was actively expanding its domain name portfolio at the time. The Respondent contends that the offering for sale of a four-letter, non-distinctive, and pronounceable domain name that corresponds to a common name and surname is not illegitimate. The Respondent further contends that the Complainant has no monopoly on this widely used name, surname, acronym, and mark, and its rights do not preclude the general marketing of the disputed Domain Name to any of the various uses to which it may be put, for which it has a legitimate commercial value independent of the Complainant’s trademark.

Held: The disputed Domain Name reflects an Indian personal name, an acronym signifying many diverse entities, and a trademark that has been registered by third parties in a number of countries. It can, therefore, be accepted that the disputed Domain Name may be legitimately used for different purposes unrelated to the Complainant as long as there is no targeting of the same. The Respondent submits that its business includes the acquisition and resale of short, acronymic, or name and surname domain names. There is no evidence that the Respondent knew of the Complainant when it acquired the disputed Domain Name in 2007, and, in any event, the Complainant did not apply for its trademark until December 2008 and did not obtain its registration until July 2009.

The disputed Domain Name is currently offered for sale to the general public, and the Respondent has never contacted the Complainant or placed any content relating to the Complainant on the disputed Domain Name. All of these circumstances support a finding that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name and advertised it without targeting the Complainant. The Panel further finds that the Respondent did not register the disputed Domain Name in bad faith targeting the Complainant or its trademark rights because the Complainant had no trademark rights at the time that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name.

RDNH: On the one hand, the Complainant chose as its name, trademark, and several domain names a word that is an acronym and/or a word with some historical and religious meaning, which the Complainant probably knew or could have ascertained before it instituted the proceeding. It might, therefore, be said that the Complainant knew or could have reasonably concluded that its chances of success were somewhat doubtful. Moreover, the Complainant also knew that it had no trademark rights at the time the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in 2007 and that its chances of proving registration of the domain name in bad faith were, therefore, slim.

Putting all of the considerations together, the probability is that it may have simply been over-optimistic that it could bring its claim within the confines of the UDRP, given the obstacles to success mentioned above. That does not mean, however, that it was acting in bad faith or that it was harassing the Respondent or intending to do so. It is at least possible that it wanted to exercise a good faith intention of taking steps to protect its trademark and that it was taking steps to bring that objective about, which is legitimate, rather than that it was “primarily” harassing the Respondent. On balance, therefore, the Panel is of the view that this is not a case that comes within the ambit of Paragraph 15(e) of the Rules.

Complaint Denied

Complainant’s Counsel: lexTM Rechtsanwaelte, Germany

Respondent’s Counsel: John Berryhill, Ph.d., Esq., United States

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: The Panel laid down a particularly helpful yardstick when gauging whether a Domain Name is capable of legitimate use. Noting that the Domain Name “reflects an Indian personal name, an acronym signifying many diverse entities, and a trademark that has been registered by third parties in a number of countries” the disputed Domain Name “may be legitimately used for different purposes unrelated to the Complainant as long as there is no targeting of the same”. As you can see, there are really two parts to the analysis here.

First, the Panel must determine if there are any plausible good faith uses for the Disputed Domain Name. Once the Panel determined that there are indeed, then the Panel must also determine whether regardless of the Domain Name’s capability for being used in good faith, whether the Respondent nevertheless targeted the Complainant’s mark. Here, the Panel concluded that “the case file as presented does not indicate that the Respondent’s aim in registering the disputed domain name was to profit from or exploit the Complainant’s GOPA trademark”, which is the fundamental question to be answered in the UDRP.

Material Time for Proving Common Law Trademark Rights is Before Domain Name Registration

Tiger Aesthetics Medical, LLC v. pan xin yong, NAF Claim Number: FA2502002140282

<tigeraesthetics .com>

Panelist: Mr. Richard Hill

Brief Facts: The Complainant provides a wide range of goods and services, with a focus on cosmetic treatments and soft tissue augmentation and reconstruction, under the trademark TIGER AESTHETICS, to customers through operations in the U.S. The Complainant asserts that it has established significant public recognition and common law rights in the TIGER AESTHETICS mark through continuous and substantial use since at least March 2024. The Complainant engages in significant marketing, promotional, and advertising activities related to its TIGER AESTHETICS mark, including on its website located at <tiger-aesthetics .com> (registered on March 30, 2024; Live between May and August 2024). The disputed Domain Name was registered on October 30, 2024 and resolves to a parked page, where it is offered for sale at US $2,00,000.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is not making a bona fide offering of goods or services through the disputed Domain Name, nor a legitimate noncommercial or fair use. Instead, the only use of the disputed Domain Name is to offer it for sale at a price in excess of out-of-pocket costs. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name with constructive and/or actual knowledge of the Complainant’s mark. The Respondent contends that he searched ‘tiger aesthetics’ at USPTO .gov (provided no live trademark) and also at OpenCorporates .com (no active exact business name existed). The Respondent further contends that tiger is a generic term, a person’s last name, and other active business sites are using ‘tiger aesthetics’, such as TealTigerAesthetics .com and TrixieTigerAesthetics .com.

Held: In general, where a respondent registers a domain name before the complainant’s trademark rights accrue, panels will not normally find bad faith on the part of the respondent; see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.8. The Complainant asserts common law rights in its mark, but fails to provide sufficient evidence to establish the date on which it may have acquired common law rights in the TIGER AESTHETICS mark. The Panel finds, on the balance of the evidence before it, that the Complainant has failed to satisfy its burden of proving that it acquired common law rights in the mark TIGER AESTHETICS before the disputed Domain Name was registered on October 30, 2024. The Panel also finds that the Complainant has failed to satisfy its burden of proving that the Respondent’s intent in registering the disputed Domain Name was to unfairly capitalize on the Complainant’s nascent trademark rights. Thus, the Panel finds that the Complainant has failed to satisfy its burden of proving bad faith registration of the disputed Domain Name, and it will dismiss the Complaint.

This dismissal is, of course, without prejudice to any national court proceedings that the parties may wish to envisage. The Panel notes that, as stated in 4.18 of the cited Overview, the instant case could be refiled if the Complainant can present new material evidence that was reasonably unavailable to it when the instant case was filed, in particular concerning the Respondent’s intent in registering the disputed Domain Name. Indeed, the instant Panel explicitly gives the Complainant leave to refile on such grounds; see RapidShare AG and Christian Schmid v. Fantastic Investment Limited, FA 1338403 (Forum Oct. 8, 2010) (“Complainant argued that the prior panel had given leave to Complainant to submit a fresh complaint. The Panel may find the prior panel’s approval supports a rehearing of the dispute involving the domain name.”).

Complaint Denied

Complainant’s Counsel: David M. Perry of Blank Rome LLP, Pennsylvania, USA

Respondent’s Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: As the Panel clearly noted, the material time for proving common law trademark rights is before registration of the Disputed Domain Name. This is an error that we see all to often made by Complainants. Complainants will often prove their common law trademark rights as of the filing of the Complaint, such as by providing recent press clippings. At other times, Complainants will not identify when their alleged common law trademark rights even crystalized.

A Complainant who proves common law trademark rights merely as of the filing of the Complaint – or indeterminately timed common law trademark rights, will nevertheless have met the requirements under the first prong of the UDRP test, i.e. that it has a trademark. But it will have failed to demonstrate that it had any reputation at the material time for proving bad faith registration – which is before the registration of the Domain Name.

Respondent’s Willingness to Sell the Legitimately Owned Domain Name

HYDAC Technology GmbH v. Rabbani Hussain, Digital Motive Inc, WIPO Case No. D2024-4947

<hydacservice .com>

Panelist: Ms. Marina Perraki

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1963, manufactures filter devices and filters for heating, steam-generating, refrigerating, drying, ventilating, water supply, water treatment, air-conditioning, and sanitary installations and apparatus and provides respective services. The Complainant is the owner of trademark registrations for HYDAC, including the Indian trademark registration dated May 16, 1989, for goods in International Class 7. The Domain Name was registered on March 22, 2022, and at the time of filing of the Complaint, led to a website offering services similar to those of the Complainant, namely air conditioning repair services using the words “HYD” and “AC Services”.

The Respondent did not formally reply to the Complainant’s contentions. In his reply to the Procedural Order No. 1, The Respondent claimed that the Domain Name “HYDAC” was chosen as a combination of “HYD” (an abbreviation for Hyderabad, where his business operates) and “AC” (air conditioning), reflecting his services, and added that he was unaware of the Complainant’s trademarks prior to the Complaint. Finally, the Respondent expressed his willingness to sell the Domain Name to the Complainant “at a fair market value to compensate for the time, effort, and resources” he has invested.

Held: The Panel finds that, before notice to the Respondent of the dispute, the Respondent used the Domain Name in connection with a purportedly bona fide offering of services, see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.2. The Panel finds that these circumstances confer upon the Respondent’s rights and legitimate interests in respect of the Domain Name for the purposes of the Policy.

Further, the Respondent in the present case justified the choice of the terms “hyd” and “ac”, as stemming from his place and nature of business respectively when registering the Domain Name. The reputation and long-standing use of the Complainant’s mark, including in the field of air conditioning-related commerce, may be indicative that the Respondent knew of the Complainant; however, the Respondent has expressly denied such knowledge. In these circumstances, the Panel finds that the evidence in the case file as presented by the Parties, does not indicate that the Respondent’s aim in registering the Domain Name was to profit from or exploit the Complainant’s trademark, rather than registering the Domain Name for his air conditioning repair related business in Hyderabad.

As regards the willingness of the Respondent to sell the Domain Name, panels have generally found that where a registrant has an independent right to or legitimate interest in a domain name, an offer to sell that domain name would not be evidence of bad faith (see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.1.1). In the present case the Panel finds that the willingness of the Respondent to sell the Domain Name “at a fair market value to compensate for the time, effort, and resources” he has invested, as such is not enough to establish bad faith, in view of the time of registration of the Domain Name, the fact that some use was made of the brand name of “HYD” (Hyderabad) and “AC” (air conditioning), “HYD air condition”, and the explanation provided by the Respondent.

Complaint Denied

Complainant’s Counsel: L. S. Davar & Co., India.

Respondent’s Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: I particularly appreciate the Panel’s nuanced appreciation of the relevance of offering a domain name for sale, based upon the WIPO Overview. As the Panel noted:

“As regards the willingness of Respondent to sell the Domain Name, panels have generally found that where a registrant has an independent right to or legitimate interest in a domain name, an offer to sell that domain name would not be evidence of bad faith for purposes of the UDRP, irrespective of which party solicits the prospective sale.”

This is exactly right. Offering to sell a cybersquatted domain name is one thing. But offering to sell a domain name that the Respondent has rights to, is quite another. If a registrant has a legitimate interest in a domain name and did not register it in bad faith, as in this case, the registrant is entitled to offer its business asset for sale at market price and this is not bad faith (See Etam, plc v. Alberta Hot Rods, WIPO Case No. D2000-1654). Moreover, as a lawful registrant, a Respondent has the right to sell a Domain Name for whatever price it deems appropriate regardless of the value that the Complainant or an appraiser may ascribe to the domain name (See; Personally Cool v. Name Administration, NAF Claim No. FA1212001474325).

I also appreciate the Panel’s sound reasoning regarding legitimate interest. Here, the Complainant had registered trademark rights which long pre-dated the Domain Name registration in 2022, including in India where the Respondent resides. Nevertheless, the Panel found that the Respondent had satisfactorily demonstrated that “before notice to Respondent of the dispute, Respondent used the Domain Name in connection with a purportedly bona fide offering of services” and that as a result, “these circumstances confer upon Respondent rights and legitimate interests in respect of the Domain Name for the purposes of the Policy”. Another Panel may have incorrectly imported the concept of constructive notice into the UDRP and then found that the Respondent could not have any legitimate interest in the Domain Name as a result of using the Domain Name in an infringing manner. But that would have been a misapprehension of the UDRP.

In the recent case of MidWasteland, Panelist David Bernstein clearly explained why constructive notice has generally not been incorporated into the UDRP:

“Even though a registered trademark constitutes constructive notice under U.S. trademark law, that concept has generally not been incorporated into the UDRP as a basis to find bad faith registration. Akamai Technologies, Inc. v. Cloudflare Hostmaster / Cloudflare, Inc., FA2201001979588 (Forum March 9, 2022)(“constructive knowledge is insufficient to demonstrate bad faith”).

That is because a finding of bad faith under the Policy requires some element of knowledge, even if knowledge is inferred by the facts or established through willful blindness. The refusal to treat constructive notice as actual knowledge is especially appropriate here, where even actual knowledge would not necessarily have established bad faith.” [emphasis added]

As you can see, “knowledge” (of the Complainant’s mark) is generally required for there to be bad faith in the UDRP. Without knowledge – even if it is inferred knowledge – there can be no intentional targeting of a Complainant’s mark – the fundamental requirement under the Policy. This is a good place to include a reminder of the implications that would result if constructive knowledge were to be imported into the UDRP, as explained in The Way International v. Diamond Peters (WIPO-D2003-0264):

“As to constructive knowledge, the Panel takes the view that there is no place for such a concept under the Policy. The essence of the complaint is an allegation of bad faith, bad faith targeted at the Complainant. For that bad faith to be present, the Respondent must have actual knowledge of the existence of the Complainant, the trademark owner. If the registrant is unaware of the existence of the trademark owner, how can he sensibly be regarded as having any bad faith intentions directed at the Complainant? If the existence of a trademark registration was sufficient to give the Respondent knowledge, thousands of innocent domain name registrants would, in the view of the Panel, be brought into the frame quite wrongly”. [emphasis added]

About the Editor:

He is an accredited panelist with ADNDRC (Hong Kong) and MFSD (Italy). Previously, Ankur worked as an Arbitrator/Panelist with .IN Registry for six years. In a advisory capacity, he has worked with NIXI/.IN Registry and Net4 India’s resolution professional.