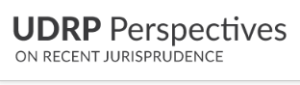

Register today for the CIIDRC’s Domain Disputes 2024: Conference & Panelist Workshop! In-Person in Vancouver, Canada, and Via Zoom.

A series of thought-provoking discussions on hot topics and best practices. The morning will feature sessions that are open to all. They will delve into UDRP statistics with Doug Isenberg, explore the current domain name market with Zak Muscovitch, and gain insights on how to avoid pitfalls in UDRP cases from Steve Levy. Then, Richard Levy and Michael Erdle will discuss refiled complaints, offering valuable perspectives and strategies. The morning will wrap up with Gerald Levine’s presentation, ensuring a rich and informative conclusion to our morning session. We are looking forward to seeing you there! Register here: https://arbitration.vaniac.org/ciidrc-2024-udrp-panelist-training-and-workshop-event-registration/. The afternoon sessions will be open to Panelists only with workshops to be led by Steve Levy, Zak Muscovitch, and Doug Isenberg.

SIGN UP FOR THE CONFERENCE & PANELIST WORKSHOP HERE

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.35), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ How to Assess the History of MinuteMen(.com) (minutemen .com *with commentary)

‣ A Trademark is Not Enough (mangels .com *with commentary)

‣ Can the UDRP be Used to Adjudicate Alleged Trademark Infringement Cases? (teachella .net and teachella .org .com *with commentary)

‣ Complainant is “Not the Exclusive User” and Has Not Demonstrated Why it has “Any Greater Right” Than Other Companies Using the Mark” (cronosgroup .com *with commentary)

‣ Complainant Alleges Ownership Change but Lacks Sufficient Evidence (zapa .com *with commentary)

How to Assess the History of MinuteMen(.com)

Minute Men, Inc. v. Domain Administrator / PTB Media Ltd, NAF Claim Number: FA2407002106746

<minutemen .com>

Panelist: Mr. Alan L. Limbury (Chair), Ms. Dawn Osborne and Mr. Steven M. Levy, Esq.

Brief Facts: The Complainant, since 1968, has provided employment staffing and related services under the MINUTEMEN mark. The Complainant’s trademark was registered before USPTO on April 16, 2024 and additionally, it also claims common law rights. On April 13, 1998, and January 3, 2020, respectively, the Complainant registered the domain names <minutemeninc .com> and <minutemenstaffing .com>. The Complainant advertises its services, using the MINUTEMEN mark at <minutemenstaffing .com> and through 35 brick-and-mortar locations in the United States. As a result of its advertising efforts and over 50 years of use, the Complainant claims that its services offered under the MINUTEMEN mark have become well-known. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is undoubtedly familiar with and attempting to trade off the Complainant’s goodwill in the MINUTEMEN mark, which the Complainant has used for over thirty years. The Respondent is not using the disputed Domain Name for legitimate purposes (See Telstra Corp. v. Nuclear Marshmallows, D2000-0003) but instead for pay-per-click links related to the Complainant’s offerings and has listed the disputed Domain Name for sale at an excessive price of US $500,000.

The Respondent provides a declaration of its Portfolio Manager, that on or around February 18, 2006, as part of its domain name investment strategy of occasionally purchasing or acquiring through auction generic domain names that were deemed to be good investments, the Respondent purchased the <minutemen .com> common word Domain Name along with 8 other common word domain names as part of an investment portfolio. The Respondent has used the disputed Domain Name for PPC advertising since 2006, with links auto generated by parking services and unrelated to the Complainant. Recently, employment-related links appeared due to changes in these services, but the Respondent was unaware and requested its parking service provider for their removal upon learning of the issue. A search of the USPTO database shows many third-party marks for both MINUTEMEN and MINUTE MEN, which belies the Complainant’s claims of exclusive or popular association of the term with the Complainant. Further, there is no evidence that there is widespread global awareness of the Complainant as of today or in February 2006 when the Domain Name was acquired.

Held: At the time of filing of this Complaint, the disputed Domain Name resolved to a parked web page indicating that it is for sale and displaying PPC links to services of the kind provided by the Complainant. These circumstances, together with the Complainant’s assertions, are sufficient to constitute prima facie showing of the absence of rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name on the part of the Respondent. It is well established that the domain name registrant is responsible for PPC links, whether or not the registrant was aware of them. Accordingly, the Panel finds that, although the Respondent’s website for many years displayed PPC links unrelated to the Complainant’s business, its current use deprives the Respondent of rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name. The Respondent’s recent use of the disputed Domain Name to display PPC links relating to the Complainant’s business is also bad faith use under Paragraph 4(b)(iv) of the Policy. However, such evidence is not necessarily conclusive, since it may be weighed against any evidence of good faith registration.

The Complainant’s Supplementary Submission shows that by the time the Respondent acquired the Domain Name in 2006, the Complainant’s reputation was well-known in few US states and that the Complainant did then have common law rights in the MINUTEMEN mark. However, the Complainant has not shown that it then had or now has a significant reputation within the full breadth of the United States or internationally. The Domain Name comprises two dictionary words in common use and evocative of the American Revolutionary War. Further, many American businesses use the name for all manner of goods and services. Against this backdrop, the majority of the Panel finds it unlikely that the Respondent was aware of or targeted the Complainant. Rather, its claim to be a domain name investor which purchases brandable, and inherently valuable domain names is supported by the evidence. In addition, it does not meet the “inconceivability” standard set out in the Telstra Corp. v. Nuclear Marshmallows, D2000-0003. Taking all the circumstances of this case into account, the majority finds that the Complainant has failed to show that the Domain Name was registered in bad faith.

Dissenting Opinion from Ms. Dawn Osborne: I wish to record that I cannot agree with the conclusions of the Panel as to registration and use in bad faith, given that the principal director of the Respondent is also a principal director of the related company PortMedia that acquired the Domain Name as the Registrant’s predecessor in title in 2006. That predecessor in title Port Media has been found to have registered and used domain names in bad faith several times under the UDRP suggesting a pattern of bad faith activity. Further, the Complainant had been operating in the United States for over 38 years with an annual turnover in 2006 of 120 million USD, and its domain name <minutemeninc .com> had been in use for nearly eight years, at the time the Respondent acquired the Domain Name in 2006. It is not really believable to me that in 2006 when considering the purchase of the Domain Name as a professional re-seller the Respondent would not have discovered the existence of the Complainant due to the well-established nature of the Complainant’s business at that time.

The responsibility of the Respondent for the use of the Domain Name for pay-per-click links for competing services to the Complainant and the lack of any evidence that the Respondent has been trying to use or encourage purchase or use of the Domain Name for military history purposes and the extremely high price under which the Domain Name has been offered for sale US $500,000 suggesting that the Respondent knew of the fact that the rights of the Complainant in the name MINUTEMEN made the Domain Name worth such a sum. I would have held for the Complainant in this case and disagreed with the conclusions of the Majority of the Panel. I believe that it is more likely than not that the Respondent through its common director with its predecessor in title (the subject of several adverse decisions under the UDRP) was aware of the rights of the Complainant at the time of acquisition of the Domain Name. Having bided its time the Respondent is now seeking to profit from its acquisition of the Domain Name which was at the time of acquisition, and is now, extremely valuable.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: John L. Krieger of Dickinson Wright PLLC, Nevada, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Jason Schaeffer of ESQwire .com, New Jersey, USA

Case Comment by ICA Director, Nat Cohen:

Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

The <minutemen .com> decision raises questions about two key aspects of UDRP jurisprudence – assessing legitimate interest and drawing inferences as to registration in bad faith. Although the majority of the Panel came to the right decision with respect to dismissing the Complaint, I will attempt to show in this comment that the Panel inappropriately applied the rights and legitimate interest test, and that the dissenting panelist reached the wrong conclusion on registration in bad faith.

Some people sell widgets. I sell domain names.

What I ask of the UDRP is that it shows some respect for my business and livelihood and for my fellow domain name investors.

I once owned <minutemen .com>. I bought it in a bulk deal along with a few other dictionary-word domain names from another domain name investor in October 2003. When, in early 2006, I was trying to raise funds for the downpayment on our current house, I offered many of the domain names I had recently acquired to other domain name investors so I could recoup the cash I had spent for those domain names and put those funds towards the house purchase instead. I joke with one of my friends who bought several of the domain names that there is a room in the house named after him.

The Respondent was one of the domain name investors who purchased some of the domain names I was offering for sale. He acquired <minutemen .com> along with a few of other dictionary word domain names. A summary of this background was presented to the panel as evidence.

Legitimate Interest

The Respondent had a legitimate interest in the Domain Name because the Respondent is a domain name investor and the Domain Name corresponded to a common term and dictionary word. As noted in the summary above and as detailed in the decision itself, the Respondent is a domain name investor with a portfolio of tens of thousands of domain names. As is often the case, the Respondent enrolled its domain names in ad-serving programs offered by Yahoo! or Google. The domain names displayed ads selected by Yahoo’s or Google’s proprietary algorithm that factors in how much advertisers are paying for clicks and which ads receive clicks among other factors. Apparently over ten years passed since the Respondent purchased the <minutemen .com> domain name from me, before ads started appearing that were related to the Complainant’s services.

That a Midwestern staffing company chose to name itself after a common term that also appears in the dictionary, and then over 25 years after the <minutemen .com> domain name was first registered, decided it would be beneficial to own and to use the domain name itself, and filed a UDRP complaint to that end, does not retroactively deprive the Respondent of a legitimate interest in the <minutemen .com> domain name. Nor does it create a justifiable inference that the Respondent acquired <minutemen .com> in a bulk purchase with other dictionary-word domain names 18 years ago with a bad faith intent to target the Complainant.

Yet the Panel found that the Respondent had no legitimate interest in the <minutemen .com> domain name. (I recognize that the decision primarily reflects the views of the author and does not necessarily fully reflect the views of the other Panelists on the Panel.) If domain name investing is legitimate, then there is hardly any more legitimate asset for an investor to hold in its portfolio than a dictionary-word dot-com domain name with demonstrated widespread appeal that has no well-known or dominant commercial user.

How then did the distinguished panel reach the conclusion that the Respondent had no legitimate interest in the <minutemen .com> domain name? The answer is that the Panel relied on the misleading guidance promulgated in WIPO’s Overview in section 2.11, in a topic entitled “At what point in time of respondent conduct do panels assess claimed rights or legitimate interests?”. The answer provided is “in the present”:

Panels tend to assess claimed respondent rights or legitimate interests in the present, i.e., with a view to the circumstances prevailing at the time of the filing of the complaint.

The Panel explicitly followed this guidance:

The relevant date to determine whether the Respondent has rights or legitimate interests in the domain name is the date of notice to Respondent of the dispute, in this case the filing date of the Complaint, July 17, 2024. WIPO Overview of WIPO Panel Views on Selected UDRP Questions, Third Edition (WIPO Overview 3.0) at par. 2.11. Despite Respondent’s submission of archived screenshots showing the display of generic PPC links from 2006 through 2009, and redirection to the SEDO auction site from 2015 through 2018, at the time that the Complaint was filed the domain name resolved to a parked webpage indicating that the domain name is for sale and displaying PPC links to services of the kind provided by Complainant, namely “Employment Staffing”, “Employee Self Service Portal Software” and “Find Temp and Direct Hire Employee”.

The Panel found that because Google’s algorithm was displaying ads related to the Complainant at the time the dispute was filed, the Respondent had no legitimate interest in the <minutemen .com> domain name:

It is well established that the domain name registrant is responsible for PPC links, whether or not the registrant was aware of them. Accordingly, the Panel finds that, although Respondent’s website for many years displayed PPC links unrelated to Complainant’s business, its current use deprives Respondent of rights or legitimate interests in the domain name.

The guidance that WIPO provides conflicts with the clear language of the UDRP. The Policy in 4(c)(i) states (emphasis added):

(i) before any notice to you of the dispute, your use of, or demonstrable preparations to use, the domain name or a name corresponding to the domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services; or

Legitimate interest is to be assessed looking at how the domain name was used prior to the commencement of the dispute, not “in the present…at the time of the filing of the complaint” as stated in WIPO’s Overview.

While some have pointed to the language of 4(a)(ii) that speaks of legitimate interest in the present tense:

(ii) you have no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name;

this refers to an allegation made by the Complainant in the Complaint. Section 4(c)(i) indicates that the Respondent can sufficiently rebut this allegation by demonstrating the acquisition of a legitimate interest prior to the commencement of the dispute. Unless the Complainant can successfully argue that the Respondent’s legitimate interest, once gained, has somehow been extinguished, the legitimate interest in the Disputed Domain Name would continue to the present day.

To offer an analogy, if the criteria were “reputation as a tennis player”, would it be accurate for a Panel to deny Roger Federer a reputation as a tennis player because at the time of the filing of the Complaint he is no longer competing professionally and the Panel declares that that is the only time period in which he is eligible to establish his reputation, or can his reputation earned over a lengthy career continue to the present day after his playing career has ended? In a similar vein, a Respondent can rebut an allegation that it has no legitimate interest currently by demonstrating that it previously had a legitimate interest, and absent evidence to the contrary, that legitimate interest therefore continues to the present day.

To assess legitimate interest prior to the commencement of the dispute is the only sensible approach. If a company owner had registered a domain name and used it as the website of his business for 20 years, this is a clear example of the owner having a legitimate interest in the domain name. If the business then shuts down yet the owner retains the domain name because of a sentimental attachment or because the domain name is an inherently valuable investment grade domain name, does this deprive the owner of a legitimate interest in the domain name? Yet according to WIPO’s guidance, if a complaint is then filed against the domain name, the Panel is directed to assess legitimate interest only at the time the complaint is filed, where the domain name may not be being put to any use whatsoever.

Similarly, in the <minutemen .com> dispute, the Respondent acquired the domain name as part of its “stock in trade” as an inherently valuable dictionary-word domain name and put it to a non-objectionable use for over a decade. Does this not comply with the language of the UDRP that before notice of the dispute the domain name was used for a bona fide business purpose?

Bad Faith Registration

The dissenting panelist found:

Having bided its time the Respondent is now seeking to profit from its acquisition of the Domain Name which was at the time of acquisition, and is now, extremely valuable. Its value is predictably due to a large degree to the rights of the Complainant in the MINUTEMAN name both in terms of the desirability of the Domain Name to the Complainant and due to the traffic that the Complainant’s rights would bring to the Domain Name in use, especially so for competitors of the Complainant who have been demonstrated to have paid for pay per clicks from the Domain Name. On the balance of probabilities I believe this is a case of both registration and use in bad faith.

The UDRP is so loosely written that it empowers each Panelist to make a finding of bad faith registration and use based on whatever evidence the Panelist wishes, no matter how flimsy or tenuous. Here the dissenting panelist found that since the Complainant existed at the time that the Disputed Domain Name was acquired and therefore it was within the realm of possibility that the Respondent was aware of the Complainant at the time it acquired the Disputed Domain Name, and that over a decade later, after the Complainant had grown considerably in size and reputation, Google’s algorithm, over which the Respondent had no control, began showing ads suggestive of the Complainant’s services, and that in the present day the Respondent has placed a substantial asking price on the Disputed Domain Name, that on the balance of probabilities, eighteen years ago, the Respondent acquired the domain name in bad faith to target the Complainant.

On the other side of the balance are the circumstances that the Respondent is a domain name investor and would naturally have an interest in acquiring appealing dictionary-word, dot-com domain names; that the Respondent only became aware of the domain name because another domain name investor (me) was offering it for sale along with other domain names from my portfolio; that the Respondent acquired the <minutemen .com> domain name in a bulk purchase along with other dictionary-word dot-com domain names; that the Respondent followed standard business practice to enroll his non-distinctive domain names in an ad-serving program whereby Yahoo! or Google determined which ads would be displayed; that for over a decade there was no use that targeted the Complainant; and that only relatively recently did Google, according to its proprietary algorithm, began displaying ads related to the Complainant; and that the Respondent is currently listing the domain name for sale for $500,000, which is not an outrageous initial asking price for a dictionary-word, dot-com domain name, as many open market transactions of similar domain names at similar prices have demonstrated.

To assess the above evidence such that the balance of probabilities tilts in favor of the Complainant, in my view reflects an unreasonable animus against domain name investors.

A Trademark is Not Enough

Mangels Industrial S.A. v. Mira Holdings, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2024-2275

<mangels .com>

Panelist: Mr. Steven A. Maier (Presiding), Mr. Jonathan Agmon and Mr. Matthew Kennedy

Brief Facts: The Brazilian Complainant specializes in steel cylinders, wheels, and galvanizing and operates a website at <mangels .com .br>. The Complainant owns various Brazilian registrations for the trademark MANGELS, including the word mark MANGELS, (October 18, 1968); and the stylized word MANGELS, (April 25, 1979). The disputed Domain Name was registered on March 29, 2019, and it appears that the Complainant was the owner of the disputed Domain Name at some point prior to the Respondent’s registration. In April 2023, the Complainant offered around US $950 twice to buy the disputed Domain Name through the Registrar’s auction platform. In May 2023, the Complainant asked the Registrar for help in finalizing the purchase and information on its automatic renewal. The Registrar replied that the Domain Name now had a new owner and would cost at least US $61,750 to reacquire. In February 2024, the Registrar clarified that the prior registration hadn’t lapsed due to non-payment but was cancelled on January 21, 2019, following a request from a representative of the Complainant to cancel “unwanted domains.”

The Complainant alleges that there is no evidence that the Respondent intends to use the disputed Domain Name for a legitimate purpose and that the Respondent’s only use has been to offer it for sale or otherwise transfer it to the Complainant, for more than out-of-pocket costs. The Respondent contends that it is a professional domain name investor and that it purchased the disputed Domain Name at auction for a price of US $2,956 because it is a short, memorable term. The Respondent also points out that “mangels” is the plural form of a dictionary word, meaning a root vegetable cultivated as a feed for livestock. It adds that it is also a surname and provides evidence of other entities making commercial use of the name MANGELS. The Respondent further contends that it had “zero knowledge” of the Complainant until the commencement of this proceeding and produces evidence that the first page of Google search results against the term “mangels” does not include the Complainant.

Held: The Panel finds there to be neither evidence nor matters to support the drawing of any inference, of such knowledge and targeting in this case. The Complainant’s trademark MANGELS, while somewhat distinctive, is not unique to the Complainant, and that name is in legitimate use by other parties both in the course of trade – though this would not necessarily assist the Respondent if it were targeting any of those brand owners – and as a personal surname. The Complainant’s trademark registrations are of limited geographical scope and the Complainant provides no evidence of the reputation and public profile of that trademark, nor any grounds on which to conclude that the Respondent was, or ought to have been, aware of its trademark when it registered the disputed Domain Name.

The Respondent, for its part, explains its rationale for its purchase and its offer to sell the domain name, comprising matters unrelated to the Complainant’s trademark. While the Respondent’s initial asking price for the disputed Domain Name of US $61,750 appears high, the Respondent has again explained, and the Panel does not find this factor to be persuasive that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name to sell it to the Complainant (or a competitor of the Complainant) in particular. In the circumstances, the Complainant has not met the burden of demonstrating, on the balance of probabilities, that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name with knowledge of the Complainant’s trademark and in order to target that trademark.

RDNH: In this case, it is apparent that the Complainant failed to renew its registration of the disputed Domain Name (and may even have requested that its registration be cancelled), before seeking to have it reinstated after the Respondent had registered it. The Complainant appears to have made initial offers in the region of US $950 to purchase the disputed Domain Name from the Respondent, but upon being informed of the Respondent’s asking price, it appears that the Complainant elected instead to commence this proceeding. In the view of the Panel, for the reasons set out in the section above, the Complaint discloses no reasonable grounds to allege that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith.

Instead, it appears to the Panel that, having failed to re-register the disputed Domain Name, and having had its offers rejected, the Complainant elected to bring the proceeding in an attempt to obtain the disputed Domain Name. While in some circumstances an unrepresented party may be excused from having commenced proceedings in such circumstances, the Complainant is legally represented in this case and should have been advised that its claim had no reasonable prospect of succeeding. While the Panel notes that the Registrar referred to proceedings under the UDRP in its reply to the Complainant dated February 2024, this did not override the duty of the Complainant, as legally advised, to ensure that there were reasonable grounds for commencing the proceeding and that the proceeding did not represent an abuse of process.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Crepaldi Advogados Associados, Brazil

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

To paraphrase the title of a James Bond film, in the UDRP, “A Trademark Is Not Enough”.

Here, though the Complainant had a longstanding trademark, the Panel noted, “the Complaint discloses no reasonable grounds to allege that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith”. The Panel noted in particular, “that the Complainant’s trademark MANGELS, while somewhat distinctive, is not unique to the Complainant, and that name is in legitimate use by other parties both in the course of trade”. In such circumstances where there is a plausible reason for having registered the Domain Name that has nothing to do with the Complainant, the Panel noted that it is incumbent upon the Complainant to provide “evidence of the reputation and public profile of that trademark, [and] any grounds on which to conclude that the Respondent was, or ought to have been, aware of its trademark when it registered the disputed Domain Name”.

This gets to the fundamental requirement of the UDRP – targeting – and that is why “a trademark is not enough”. As noted in Section 3.3 of UDRP Perspectives:

“In the absence of evidence that Respondent registered the Domain Name specifically because of the Complainant or that its value was derived exclusively from Complainant’s mark, the Complaint must fail. It is in general essential to a finding of bad faith registration and use under the Policy, that a Respondent must have targeted Complainant or its trademark, or at least had Complainant in mind, when it registered the disputed domain name.”

It is also noteworthy that the Panel did not try to second-guess the Respondent’s pricing of the Domain Name. While the Panel stated that it “seemed high”, it also noted that the Respondent had adequately explained its pricing based upon the sales of comparable domain names, including the Respondent’s own sales of single-word domain names. As set out at Section 3.5 of UDRP Perspectives:

“Panels should exercise considerable caution when attempting to draw an inference from an asking price alone. Panels are typically not experts in valuations in the domain name aftermarket nor do they typically have a clear grasp of the pricing required to support a domain investor business model.

An inference drawn from an asking pricing is best treated as confirming or undercutting a finding drawn from other evidence, rather than as the primary basis for a finding. For example, if other evidence indicates that the Respondent registered a domain name primarily for the purpose of targeting the Complainant, an exceptionally high asking price that could reasonably be justified only due to the value of the Complainant’s goodwill could assist in supporting such an inference.”

In the present case, the Panel did not find that the pricing established that the ”primary purpose” of the registration was to sell to the Complainant or to a competitor of the Complainant. As also noted in UDRP Perspectives, in some cases, an offer for sale can be an indication of bad faith, but is not necessarily in and of itself evidence of bad faith having regard to the circumstances. Panels are required, as stated in 4(b)(i) of the Policy, to determine whether an offer to sell is “primarily for the purpose of selling, renting, or otherwise transferring the domain name registration to the complainant who is the owner of the trademark or service mark or to a competitor of that complainant, for valuable consideration in excess of your documented out-of-pocket costs directly related to the domain name”.

A final word about the Panel’s declaration of RDNH. The Panel appears to have been suitably suspect of a Complainant that failed to renew its Domain Name and then engaged in low ball price negotiations before commencing a UDRP, like what occurred here. But the fundamental reason for finding RDNH in the circumstances, was as the Panel put it; “The Complaint discloses no reasonable grounds to allege that the Respondent registered and had used the disputed domain name in bad faith”. That is the crux of the matter. Where a Complaint has no reasonable prospect of succeeding (especially but not only where the Complainant is represented by counsel, as the Panel noted), that in and of itself is grounds for finding that the Complainant has pursuant to Rule 15(e), “us[ed] the Policy in bad faith to attempt to deprive a registered domain-name holder of a domain name”.

Can the UDRP be Used to Adjudicate Alleged Trademark Infringement Cases?

<teachella .net> and <teachella .org>

Panelist: Ms. Carol Stoner, Esq.

Brief Facts: The Complainant claims that it owns and produces the famous Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival and the related community CHELLA concert. The Complainant owns the exclusive rights to trademarks and service marks associated with Coachella, including CHELLA, COACHELLA, COACHELLA (stylized), and COACHELLA MUSIC FESTIVAL, which the Complainant uses in connection with its world-famous Coachella festival. The Complainant states that, in addition to these numerous registrations, which carry the presumption of validity, the Complainant also owns common law trademark rights in its Coachella marks from nearly two decades of extensive use in commerce. The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Names merely combine the letters “tea” with the entire CHELLA mark or create a portmanteau of “teach” and CHELLA and that the Respondent’s use of the domain names of <teachella .net> and <teachella .org> to promote an entertainment event (featuring music and food) in competition with those of the Complainant is not a bona fide offering of goods or services or a legitimate non-commercial or fair use under the Policy.

The Respondent contends that Teachella Foundation Inc. is a nonprofit fundraising foundation run by teachers for teachers that has been using the TEACHELLA mark for almost four years and that the Complainant incorrectly argues that the mark is a combination of TEA and CHELLA or that the mark is a portmanteau. Rather, ‘Ella’ refers to either the female gender name or the “she/her” pronoun in Spanish and the Teachella Foundation Inc. is run by an all-female leadership team. The Respondent further contends that Teachella Foundation Inc. is not in the business of music festivals but is a non-profit fundraising teaching foundation and that the Respondent offered a festival, which was not even organized or facilitated by the Teachella Foundation Inc. but is conducted by Chancla Academy.

Under additional submissions, the Complainant asserts that at the time of the instant UDRP filing, the Respondent used the disputed Domain Names to advertise its entertainment event featuring, “Live music, food varieties and market vendors” and provides a screenshot of a Wayback Machine stating that “Teachella is the biggest Teacher Appreciation festival in the world.” The Respondent, in response, contends that the Complainant only focuses on a few of the Respondent’s activities. But that the Respondent engages in many activities which evidence a bona fide offering of goods and services at the subject domain names. Specifically, Teachella Foundation Inc. is not in the business of music festivals but is a non-profit teaching foundation.

Held: The Panel has examined the Complainant’s Exhibit, including registration certificates for the COACHELLA and CHELLA Marks, encompassing a broad range of goods and services. The Panel concludes that registration with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) suffices to establish rights in a mark under Policy ¶ 4(a)(i). The question remains, whether the subject domain names <teachella.org> and <teachella.net> are confusingly similar to the Complainant’s trademarks. The Panel determines that the Respondent’s domain names of <teachella.net> and <teachella.org> contain approximate phonetic components from the Complainant’s COACHELLA and CHELLA marks, such that an ordinary Internet user who is familiar with the Complainant’s COACHELLA Marks and the Complainant’s goods and services would, upon seeing the domain names, think an affiliation exists between the Respondent’s domain names and those of the Complainant. And that the Respondent’s domain names, <teachella.org> and <teachella.net> merely combine the letters “tea” with the entire CHELLA mark. Combining a complainant’s mark with other words satisfies the confusingly similar prong of Policy ¶ 4(a)(i).

The Respondent does not use <teachella.net> and <teachella.org> for a bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate non-commercial or fair use, as the Respondent diverts internet traffic to the Respondent’s commercial website. The totality of the Complainant’s evidence constitutes a prima facie case that the Respondent lacks rights and legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Names of <teachella.org> and <teachella.net>, under Policy ¶ 4(a)(ii). Further, the Complainant has offered credible evidence that the Respondent has registered and used the disputed Domain Names in bad faith. This evidence consists of the Respondent’s actual knowledge of the COACHELLA Marks, gained through the fact that the Complainant’s COACHELLA Marks are widely known throughout the United States and the Globe. The Respondent has registered and used the confusingly similar disputed Domain Names to redirect to a website promoting an event with music and food that is not connected with the Complainant, advertising a “Rock Fest” and “come enjoy live music, food varieties, market vendors…” The use of Domain Names that are identical or confusingly similar to a complainant’s mark to divert consumers to a competing business is bad faith under the policy.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: David J. Steele of Tucker Ellis, LLP, California, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Roman Aguilera III of The Aguilera Law Firm PLLC, Texas, USA

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

Is TEACHELLA confusingly similar to COACHELLA as understood by the UDRP? It is well established that a side-by-side comparison of the domain name and the trademark determines whether the disputed domain name is confusingly similar to a Complainant’s trademark for the purposed of the UDRP. As noted in UDRP Perspectives at Section 1.8, mere “similarity” is insufficient under the Policy, it must be “confusing similarity”. Confusing similarity does not depend on evidence of actual confusion by the public. Rather, the question is whether the appearance of the domain name itself causes confusion with the trademark.

The Panel in this case, however, seems to have applied a somewhat different test in finding confusing similarity:

“Panel rules that Respondent’s domain names of <teachella .net> and <teachella .org> contain approximate phonetic components from Complainant’s COACHELLA and CHELLA marks, such that an ordinary Internet user who is familiar with Complainant’s COACHELLA Marks and Complainant’s goods and services would, upon seeing the domain names, think an affiliation exists between Respondent’s domain names and those of Complainant.”

Rather than engage in a side-by-side comparison which would likely result in a finding of similarity due to the sharing of the latter part of the respective terms (“-ella”), the Panel instead engaged in what looks to be more of a trademark law test for confusing similarity, which involves inquiring into whether there is a likelihood of confusion by the public as to the source of the services, rather than a confusing similarity in the appearance of the Domain Name when compared to the trademark. This test is broader than the UDRP-specific one and therefore can result in additionally encompassing disputed domain names that may not be considered confusingly similar under the UDRP. Under such a test for example, “BadSpaniels .com” for dog toys shaped like a whisky bottle, could be found to infringe upon “JACK DANIELS”, despite the respective terms not appearing confusingly similar as understood by the UDRP.

In my view, this approach is generally wrongheaded as it purports to treat the UDRP like it is a trademark court instead of abiding by its far more limited jurisdiction and mandate. As noted in UDRP Perspectives at Section 0.1, “The UDRP is not intended to resolve all kinds of disputes. Rather, it is only designed and intended for clear cut cases of cybersquatting. Other disputes are not intended to be resolved by the expedited and administrative nature of the UDRP procedure. That is not to say however, that a Panel could not reasonably conclude that TEACHELLA and COACHELLA are confusingly similar under the Policy. After all, TEACH and COACH are similar words, and when combined with shared and distinctive suffix, -ELLA, a case can be made for confusing similarity under the Policy – without having to apply the broader and inapplicable trademark law test. Moreover, such a conclusion of confusing similarity can arguably be drawn without even needing to examine the Respondent’s associated services, which includes a festival including a music component – which is similar to what the Complainant provides under its mark.

Which brings me to another related and troubling aspect of this decision, namely the Panel’s ruling on Rights and Legitimate Interest. The Panel concluded that the Respondent lacks any rights or legitimate interest in the Domain Name, despite the fact that the Respondent is an incorporated nonprofit in Texas and has been using TEACHELLA for almost four years in connection with a fundraising foundation. By all appearances it provides a bona fide (meaning genuine) nonprofit service and is a genuine registered nonprofit, from well before notice of the dispute. Under Rule 4(c), a Respondent will have proved its rights and legitimate interest if;

(i) before any notice to you of the dispute, your use of, or demonstrable preparations to use, the domain name or a name corresponding to the domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services; or

(ii) you (as an individual, business, or other organization) have been commonly known by the domain name, even if you have acquired no trademark or service mark rights; or

(iii) you are making a legitimate noncommercial or fair use of the domain name, without intent for commercial gain to misleadingly divert consumers or to tarnish the trademark or service mark at issue.

It certainly appears that the Respondent met the requirements of 4(c)(i), and even 4(c)(ii) perhaps, if not 4(c)(iii). Yet the Panel ruled that “Respondent does not use <teachella .net> and <teachella .org> for a bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate noncommercial or fair use, as Respondent diverts internet traffic to Respondent’s commercial website”. The Panel appears to have once again held a quasi-trademark law court hearing here. The Respondent’s use of the Domain Names may very well be found to be infringing under trademark law in a court of law, but the scope of the UDRP is far more limited. If the Respondent is offering a bona fide service but is possibly infringing the Complainant’s trademark, then the recourse should generally be to the courts rather than via the UDRP. As set out at Section 0.1 of UDRP Perspectives, the UDRP is not intended to resolve all kinds of disputes. Rather, it is only designed and intended for clear cut cases of cybersquatting. Other disputes are not intended to be resolved by the expedited and administrative nature of the UDRP procedure. The Policy requires Panels to discern those cases appropriate for resolution and to dismiss those that are not. Like the Panel stated in Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH v. Bediamond GmbH, WIPO D2023-5303, <bevigra .com>, “the disputed domain name is part of a much wider and more complex dispute that involves typical issues of trademark infringement and unfair competition law cases, and, therefore, is not taking part in a typical straightforward domain name dispute under the UDRP”. As stated in Steri-Clean, Inc. v. Jeffrey Dabdoub / Florida Property care llc, Forum FA2311002069041 <xstericlean .com>, “the determination of whether the use of a mark infringes upon the rights of a trademark owner requires a complete evidentiary record, the opportunity to present witnesses, expert opinions, and to cross examine those witnesses and experts. The evidentiary and legal issues that are required to make a finding of infringement are not appropriate to the very narrow scope of the Policy and would best be dealt with in a forum with more robust evidentiary tools.”

Complainant is “Not the Exclusive User” and Has Not Demonstrated Why it has “Any Greater Right” Than Other Companies Using the Mark”

Cronos Group Inc. v. Mira Holdings, Inc., CIIDRC Case No. 23351-UDRP

<cronosgroup .com>

Panelist: Mr. Gerald M. Levine (Presiding) Mr. Douglas M. Isenberg and Mr. Alan L. Limbury

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a Canada-based global cannabinoid company trading publicly on the Nasdaq Global Market and Toronto Stock Exchange. The Complainant has used the name “Cronos Group” since October 2016 and holds related trademark registrations for Cronos and Cronos Group in several countries for various services in the field of cannabis, with the earliest filing date in 2017. The Respondent is a professional domain name investor, who acquired the disputed Domain Name in March of 2023 in the public auction at SnapNames for US $2,849. The Respondent owns more similar “two-word” domains that it claims to have been purchased at auction as well: HydroGroup .com, GeminiGroup .com, ParkwayGroup .com, and VisionaryGroup .com.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent registered the domain at issue years after Cronos Group began using the same name and years after Cronos Group registered trademarks for Cronos and Cronos Group and that it has a history of registering trademark-abusive domains and is a serial litigant (as a respondent) before UDRP panels. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent acquired the domain to sell it for an excessive amount. At the GoDaddy domain sales website (the domain was listed for sale for $48,500), as well in the Respondent’s response to Cronos Group’s letter in which it sought $18,500.

The Respondent contends that this is consistent with its bona fide business plan of acquiring quality memorable domains to list for sale or lease to the general public, not specifically targeting the Complainant in any way. The Respondent points out that the WIPO Global Brand Database of Trademarks contains a list of 180 brand trademarks for the term “Cronos” and also several businesses marketing their goods or services under the sign “Cronos Group” that have no trademark registrations. The Respondent requests that the Panel find that the complaint was launched in bad faith and has engaged in reverse domain name hijacking as Plan B.

Held: The Complainant is a global cannabinoid company trading publicly on the Nasdaq Global Market and Toronto Stock Exchange. However, its niche market limits its reputation to interested consumers, lacking widespread market presence. On the other hand, the Respondent in this case identifies itself as an investor in domain names, who in the regular course of its business, acquires domain names at dropped domain name auctions. The Respondent has also demonstrated that CRONOS GROUP is not exclusively used by the Complainant or exclusive to it, and as earlier noted pre-existed the Complainant’s first use in commerce. The Complainant provides no evidence that the phrase has acquired secondary meaning such that the term is exclusively associated with it and none other or that its trademark has become famous or widely known. Taking all these facts into account, the Panel concludes that the Respondent’s denial of awareness of the Complainant or its mark is plausible.

The Complainant’s evidence of bad faith focuses on the Respondent’s business as an investor in domain names and is largely deprecatory. The Complainant’s arguments may all be true for it is in the nature of domain investing to buy low and sell high, but unless there is some act or conduct in addition to the desire to “maximize profits” it does not support bad faith. The Complainant cites several cases in support of its argument, but these same cases generally underscore in their reasoning that there is always something more that supports the award. Finally, the Complainant has not demonstrated why it has any greater right to the Domain Name than the other companies that use that sign in commerce. If any inference can be drawn, it would be that the acquisition of such a domain name incorporating a non-exclusive phrase has a potential market for commercial users offering goods or services in fields unrelated to the business of cannabinoids. For these reasons, the Panel finds that the Complainant has failed to establish that the Respondent is using in bad faith.

RDNH: What may appear as Plan B to a respondent may to a complainant simply be protecting its trademark from what it regards as predation. The fact that supports RDNH, in this case, hinges on both the commonness of the term “Cronos Group” and the general use by others offering non-infringing goods or services using the same commercial sign. Unless there is evidence of actual knowledge of a complainant and its mark and acquisition for an illicit purpose, no inference can be drawn of bad faith.

The Panel recognizes that in this case, the Complainant was represented in-house by a person likely unfamiliar with the jurisprudence of the UDRP. This is not an excuse for commencing a UDRP proceeding. For these reasons, the Panel finds that the Complainant launched this complaint without any evidence that the Respondent had or could have had actual knowledge of its mark when it acquired the dropped domain name at auction and that it is, indeed, a case of a Plan B attempts to deprive the Respondent of its right to hold and sell its assets on its own terms.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally represented

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

For those of you who find that the word, “Cronus” sounds familiar, but, like me, regrettably failed to take classics in university, “Cronus” in ancient Greek religion and mythology, was the leader and youngest of the first generation of Titans. And despite being Canadian, I am unfamiliar with the Complainant cannabis company. As the Panel noted; “Unless there is already an interest in cannabinoids, there is no reason to accept without evidence to the contrary that the Respondent’s managers are users of Complainant’s products or services or have any knowledge of the Complainant”. Again, we see in this case, that “a trademark is not enough”. Here, the Complainant had a trademark which predated the Domain Name registration, but there was insufficient evidence of reputation or of bad faith use that could lead to a reasonable inference of targeting.

One particularly interesting aspect of this decision is the Panel’s consideration of the fact that “prior to the Complainant’s first use in commerce of CRONOS GROUP, <cronosgroup com> had been registered to an earlier registrant…[and therefore] it can readily be deduced that when the Complainant entered the market in or around 2017, <cronosgroup .com> was not available and the Complainant instead chose to offer its online services using the domain name <thecronosgroup .com>. The Panel also noted that “taking this together with evidence that there are other users of the same term is not inconsistent with “Cronos Group” as a common phrase”.

The Panel thereby appears to have taken note of the import of the fact that even prior to the Complainant adopting its trademark, there was undeniably another party that had already selected the Domain Name and registered it. This fact contributes to the inference that while the Domain Name is distinctive in a trademark sense, the Complainant has not been the only – or even the first person – to find the term attractive. As such, and without evidence, as the Panel pointed out, of the trademark being particularly well known or exclusively associated with the Complainant lends credence to the Respondent’s position that it was unaware of the Complainant and registered it primarily because of the Complainant.

Where there are numerous third parties all using a particular brand for a variety of goods and services in disparate parts of the world, it can assist a Respondent in demonstrating that the Complainant trademark was not the primary purpose of the registration. As the Panel noted, “Complainant has not demonstrated why it has any greater right to “cronosgroup .com” than the other companies that use that sign in commerce. If any inference can be drawn, it would be that the acquisition of such a domain name incorporating a non-exclusive phrase has a potential market for commercial users offering goods or services in fields unrelated to the business of cannabinoids.”

The Panel’s observations on pricing are also particularly noteworthy. The Panel crucially stated that, “it is in the nature of domain investing to buy low and sell high, but unless there is some act or conduct in addition to the desire to “maximize profits” it does not support bad faith”. This is the exactly the right approach upon which to judge the relevance or lack thereof, of pricing, as discussed above in the Mangels case where I referenced Section 3.5 of UDRP Perspectives:

“Panels should exercise considerable caution when attempting to draw an inference from an asking price alone. Panels are typically not experts in valuations in the domain name aftermarket nor do they typically have a clear grasp of the pricing required to support a domain investor business model.

An inference drawn from an asking pricing is best treated as confirming or undercutting a finding drawn from other evidence, rather than as the primary basis for a finding. For example, if other evidence indicates that the Respondent registered a domain name primarily for the purpose of targeting the Complainant, an exceptionally high asking price that could reasonably be justified only due to the value of the Complainant’s goodwill could assist in supporting such an inference.”

As the Panel specifically noted, there must always be “something more” than pricing alone upon which to infer bad faith: “Excessive pricing and speculation may support bad faith, but these same cases generally underscore in their reasoning that there is always something more that supports the award” [emphasis added].

A final word about the Panel’s finding of RDNH in this case. The Panel found “that the Complainant launched this complaint without any evidence that the Respondent had or could have had actual knowledge of its mark when it acquired the dropped domain name at auction and that it is, indeed, a case of a Plan B attempt to deprive the Respondent of its right to hold and sell its assets on its own terms”. The Panel also noted that it is not an excuse to be unrepresented. The gist of a finding of RDNH in such circumstances is the commencement of a proceeding without disclosing any evidence of targeting. A Complainant must not commence a UDRP without a credible basis for the Complaint, as in Mangels, discussed above.

Complainant Alleges Ownership Change but Lacks Sufficient Evidence

ZAPA v. Gever, Sharon, WIPO Case No. D2024-2522

<zapa .com>

Panelist: Mr. Assen Alexiev

Brief Facts: The Complainant, established in 1972, is a French textile Company, has an online presence at <zapa .fr> (registered on June 29, 1997). It owns several trademark registrations for “ZAPA”, including the international trademark, registered on July 10, 1985. The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 3, 1996, and is inactive. The Complainant alleges that the passive holding of the disputed Domain Name by the Respondent amounts to the use of it in bad faith because the disputed Domain Name reproduces a well-known trademark, has been registered through a proxy, is not being used in good faith, and the Respondent did not respond to the Complainant’s emails.

The Complainant submits that the disputed Domain Name was registered in 1996, but there was an ownership change on June 18, 2014. The Complainant notes that at that time in 2014, the ZAPA trademark already enjoyed an undeniable reputation within the European Union and more widely on the Internet, so a simple search at this time could have informed the Respondent of the Complainant’s notoriety and prior trademark rights. The Complainant further alleges that “zapa” is not a dictionary word that describes products, services, or activities and that the disputed Domain Name is not linked to any website or any email services and is not being used in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: Given the evidence, there is no basis for concluding that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name in 2014, and in the lack of any contrary evidence, the Panel accepts that the Respondent has been the registrant of the disputed Domain Name since 1996, when it was originally registered. The Complainant also submits that the ZAPA trademark is a fanciful word and that in 2014, it already had a reputation within the European Union and more widely on the Internet, and the Respondent could not have ignored its existence, since the disputed Domain Name is identical to it. The Complainant, however, did not submit any evidence about the actual public recognition of its ZAPA trademark at any point in time, and in particular in 1996, when the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name. The printout of Google search results of the term “zapa .com” as of December 31, 2014, submitted by the Complainant as the only piece of evidence in support of its claim that its trademark had gained a reputation by that time, does not prove this, although most of the results of this search refer to the Complainant.

Since the disputed Domain Name has remained inactive for many years and there is no information about the activities of the Respondent, there is also nothing to support a conclusion that the Respondent has somehow targeted the Complainant’s ZAPA trademark with the registration and use of the disputed Domain Name. The Complainant also refers in the Complaint to the doctrine of passive holding and maintains that the passive holding of the disputed Domain Name by the Respondent should be considered as use in bad faith, as discussed in section 3.3 of the WIPO Overview 3.0. A simple Google search of the term “zapa” returns results not only related to the Complainant but shows that it has other uses. In light of these other uses of the term “zapa”, which are unrelated to the Complainant’s trademark, it is not possible to conclude that the disputed Domain Name cannot be legitimately used for purposes unrelated to the Complainant’s trademark, i.e., that there is no plausible non-infringing use to which the disputed Domain Name may be put. Therefore, considering the lack of evidence in the case about the public recognition of the Complainant’s trademark to permit an inference of targeting, the doctrine of passive holding cannot be applied to the present dispute.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: SafeBrands, France

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by Newsletter Editor, Ankur Raheja:

This well-reasoned decision deals with two crucial aspects:

a) Determining the Date of Registration

The Complainant argued that an ownership change occurred on June 18, 2014, as it would have been easier to prove the well-known status of the mark in 2014 compared to 1996. The Complainant noted “that at that time in 2014, the ZAPA trademark already enjoyed an undeniable reputation within the European Union and more widely on the Internet, so a simple search at this time could have informed the Respondent of the Complainant’s notoriety and prior trademark rights.” The Respondent did not take part in these proceedings.

The Panelist rightly rejected the Complainant’s contentions as the evidence did not in fact reveal any real change in ownership, but rather the earlier set of historical data revealed the Respondent as registrant while the subsequent one showed a privacy service, thereby not demonstrating that “the registrant of the disputed domain name was a different person before that date”. The Panel further noted, “however that none of the present assessments would be any different if the acquisition date was seen as 2014”, given the facts and circumstances of this case.

b) Doctrine of Passive Holding:

As noted at Section 3.7 of UDRP Perspectives, the concept of “passive holding” refers to the “non-use” of a disputed domain name. It originates with the Telstra case in 2000.

As Section 3.7, supra further notes: “Crucially, the Telstra test requires a strong reputation of the mark and the impossibility of conceiving any plausible or actual good faith use of the particular domain name. Such a determination would generally arise only where the disputed domain name corresponds to a particularly distinctive and famous mark. Where a domain name is unused, it may be considered to be “passively held” but that alone does not amount to bad faith use absent meeting the narrow requirements of the Telstra test.”

Notably, the Panel perfectly applied the proper Telstra test in this case by inter alia, concluding that the Complainant failed to prove that “there is no plausible non-infringing uses of the term”, particularly given the numerous third party uses unrelated to the Complainant, stating as follows:

“A simple Google search of the term “zapa” returns results not only related to the Complainant, but shows that it has other uses. In light of these other uses of the term “zapa”, which are unrelated to the Complainant’s trademark, it is not possible to conclude that the disputed domain name cannot be legitimately used for purposes unrelated to the Complainant’s trademark, i.e., that there is no plausible non-infringing use to which the disputed domain name may be put. Therefore, also considering the lack of evidence in the case about the public recognition of the Complainant’s trademark to permit an inference of targeting, the doctrine of passive holding cannot be applied to the present dispute.”

About the Editor:

He is an accredited panelist with ADNDRC (Hong Kong) and MFSD (Italy). Previously, Ankur worked as an Arbitrator/Panelist with .IN Registry for six years. In a advisory capacity, he has worked with NIXI/.IN Registry and Net4 India’s resolution professional.

Here, though the Complainant had a longstanding trademark, the Panel noted, “the Complaint discloses no reasonable grounds to allege that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith”. The Panel noted in particular, “that the Complainant’s trademark MANGELS, while somewhat distinctive, is not unique to the Complainant, and that name is in legitimate use by other parties both in the course of trade”. In such circumstances where there is a plausible reason for having registered the Domain Name that has nothing to do with the Complainant, the Panel noted that it is incumbent upon the Complainant to provide “evidence of the reputation and public profile of that trademark, [and] any grounds on which to conclude that the Respondent was, or ought to have been, aware of its trademark when it registered the disputed Domain Name”.

Here, though the Complainant had a longstanding trademark, the Panel noted, “the Complaint discloses no reasonable grounds to allege that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith”. The Panel noted in particular, “that the Complainant’s trademark MANGELS, while somewhat distinctive, is not unique to the Complainant, and that name is in legitimate use by other parties both in the course of trade”. In such circumstances where there is a plausible reason for having registered the Domain Name that has nothing to do with the Complainant, the Panel noted that it is incumbent upon the Complainant to provide “evidence of the reputation and public profile of that trademark, [and] any grounds on which to conclude that the Respondent was, or ought to have been, aware of its trademark when it registered the disputed Domain Name”.