We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (Vol. 3.22), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with commentary from our Director, Nat Cohen; General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch; and Special Guest, Igor Motsnyi.

‣ Is a Registrar Landing Page Evidence of a Respondent’s Bad Faith? (decathlons .org *with commentary)

‣ What’s the Difference Between a Registrant and a Privacy Service? (MarkelGroup .com *with commentary)

‣ Proving Bad Faith When the Registration Date is Unknown (theChosenTV .com *with commentary)

‣ Not a Painless Experience for the owner of Painless.com, once put to Descriptive Use (painless .com)

‣ Website Changed After Filing Complaint (Shopify-Analytics .com)

—

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

Many thanks to the Digest readers who answered Zak’s call for examples of disputed domain names that combine two respective trademarks. Gerald Levine provided examples from his new upcoming book, and Claire Kowarsky reminded me that the domain name referenced at the WIPO workshop was <IBMappleMicrosoftATandTveriszonTmobile .com>, Case No. D2022-1073. Thank you to both! If you have any more, send them in!

Is a Registrar Landing Page Evidence of a Respondent’s Bad Faith?

Decathlon v. Doug Gursha, WIPO Case No. D2023-0987

<decathlons .org>

Panelist: Mr. Ike Ehiribe

Brief Facts: The French Complainant is a major French manufacturer and specialises in the conception and retailing of sporting and leisure goods. In April 2022, the Complainant employed 105,000 employees worldwide with annual sales of EUR 11.4 billion. In 2021, the Complainant is on record as having operated 1,747 stores throughout the world. The Complainant owns the registration of the DECATHLON mark in France since April 22, 1986; in the European Union since April 28, 2004; and International Trademark since December 20, 1993. The Complainant also offers for sale it’s sporting and leisure goods online, through its official websites located at <decathlon.fr> (registered on June 29, 1995) and <decathlon .com> (registered on May 30, 1995). The well-known character of the trademark DECATHLON has been also recognised in the context of decisions rendered under the UDRP.

The US Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name on March 3, 2021, which resolves to a website hosting a parked page with pay-per-click links relating to sports and commercial stores, in competition with the Complainant. The Complainant alleges that it is highly likely that the Respondent knew of the Complainant and its well-known trademarks when the Respondent decided to register the disputed Domain Name, considering that, any search of the term/mark DECATHLON conducted with a Google search engine would lead to the Complainant’s websites and its products. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent is intentionally creating confusion in order to divert consumers from the Complainant’s website to its own website which is not used to promote a bona fide offering of goods or services, nor to serve a non-commercial legitimate purpose but to host a parked page. The Respondent did not reply to the Complainant’s contentions.

Held: The evidence adduced by the Complainant clearly demonstrates that the Respondent is not using the disputed Domain Name for a bona fide offering of goods and services or a legitimate non-commercial or fair use purpose considering that the disputed Domain Name resolves to a website hosting a parked page with links that compete with and capitalize upon the reputation and goodwill associated with the Complainant’s trademark. Instead, as argued by the Complainant, the Respondent is using the disputed Domain Name to cause confusion by diverting the Complainant’s customers from its website. The Panel is therefore satisfied that the Complainant has established the lack of rights and legitimate interests on the part of the Respondent.

The Panel considered a number of factors to arrive at the conclusion that the Respondent engaged in bad faith registration and has continued to engage in bad faith use. As correctly articulated by the Complainant, the Respondent must have known of the prior existence of the Complainant and the Complainant’s worldwide rights in the DECATHLON trademark before electing to create the disputed Domain Name in March 2021. As the Complainant argues, an Internet search would have revealed to the Respondent of the Complainant’s websites, the worldwide reputation of the Complainant’s registered trademarks, registered domain names through which it conducts its business worldwide, and it’s sporting or leisure products.

Further attention has been drawn by the Complainant to the Respondent’s deliberate acts of causing confusion in the minds of Internet users for commercial gain by diverting them to the Respondent’s website which resolves to parked pages with links directly related to the Complainant’s business activities and the setting up of MX servers configured on the disputed Domain Name with the likely intention to send and receive emails as all evidence of intentional bad faith use. Accordingly, the Panel is satisfied that the Complainant has established the registration and bad faith requirement being the third element of the Policy.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: AARPI Scan Avocats, France

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by Nat Cohen: Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

Are PPC Ads on a Registrar Supplied Default Landing Page Evidence of the Respondent’s Bad Faith?

The question of who is responsible for content appearing on registrar default landing pages has troubled UDRP panels ever since registrars began offering such pages over 15 years ago. Some panels find that the respondent is ultimately responsible for the content that appears on its registered domain name. Other panels find that the content on registrar landing pages does not reflect the intent of the respondent.

This issue arises once again in the recent decathlons.org dispute. This offers us the opportunity to closely examine the issue to see if doing so allows us to shed light on the question.

In the <declathons .org> dispute, the Complainant, Decathlon, a large French-based sports retailer with operations across most of the globe, alleged, in part, “On the question of bad faith use, the Complainant alludes to the fact that the Disputed Domain Name is used to redirect Internet users to a parking page with links directly related to the Complainant’s business activity”. The Respondent did not submit a reply and defaulted.

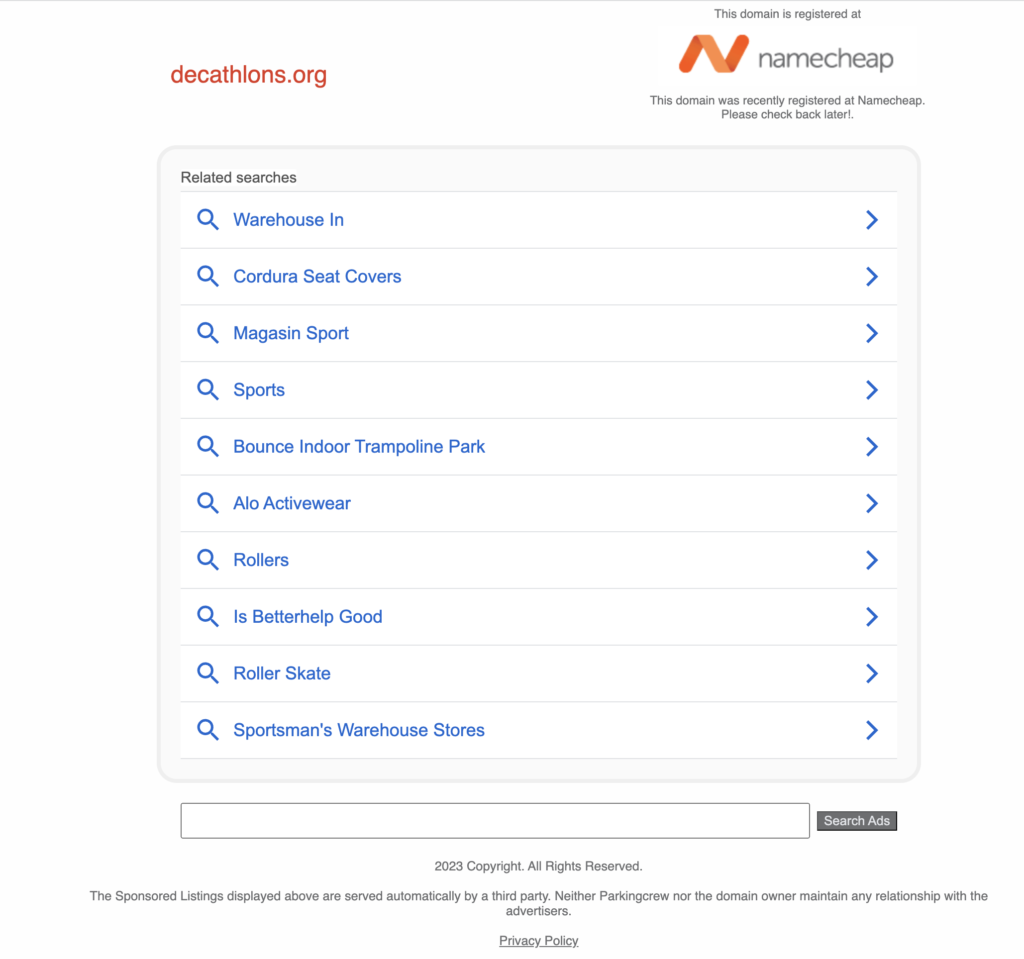

Here is a snapshot of the page in question:

We see that this appears to be a page created by the Registrar, NameCheap. It is prominently branded as NameCheap. The statement at the top of the page, “This domain was recently registered at NameCheap”, suggests that the Respondent has not yet put up its own page. This is further clarified in the disclaimer at the bottom: “The Sponsored Listings displayed above are served automatically by a third party. Neither Parkingcrew [the parking company] nor the domain name owner maintain any relationship with the advertisers.” In other words, the Respondent has nothing to do with the ads that are appearing which are served by a third-party that has a relationship with the Registrar.

The issue from a UDRP perspective is whether the Respondent is responsible for the links that appear on the registrar’s default landing page.

UDRP Panels have adopted, in broad terms, two approaches to the question of responsibility for content on landing pages that registrars place on their customers’ undeveloped domain names by default. One holds the Respondent responsible for the links. The other holds that the Respondent is not responsible for the links. These two approaches appear to be unreconcilable.

This comment will attempt to show that different facts lead to different inferences. If the fact patterns are carefully distinguished, then it becomes clearer under what circumstances it is appropriate to treat the links as reflective of the Respondent’s intent, and under what circumstances it is, instead, not appropriate to hold the Respondent responsible for the content of a registrar landing page.

The key factors are:

- The degree of fame and distinctiveness of the Complainant’s mark;

- The degree of sophistication of the Respondent.

The greater the fame and distinctiveness of the Complainant’s mark and the greater the sophistication of the Respondent the more justified the inference holding that the content of the registrar landing page reflects the Respondent’s intent. The lesser the fame and distinctiveness of the Complainant’s mark and the lesser the sophistication of the Respondent, the less justified the attribution of bad faith to the Respondent for content on a registrar provided landing page.

This discussion also highlights a recurring problem in UDRP jurisprudence – a mismatch between the facts in a cited decision and the present case. At times, a holding in one case is treated as an absolute approach that can be applied indiscriminately to any other case regardless of the key differences in the facts between the two cases. Yet most holdings are highly fact specific and do not necessarily remain valid when applied to a dispute with very different facts.

For instance, in the airsculpting.com dispute, the three-member panel found:

As to the third element, it is well settled that Respondent’s claim that Uniregistry (GoDaddy) is responsible for placing the sponsored click-through links at the website to which the domain name resolves is irrelevant, as Respondent is responsible for the content of the resolving website.

Taken as a stand-alone holding devoid of context, this might appear as strong “well settled” precedent for holding a Respondent responsible for the content on a Registrar provided landing page.

Yet the decisive fact in the <airsculpting .com> dispute is that the Respondent intentionally monetized the domain name with advertising:

it is “parked” at a professional monetizer so that he [the Respondent] can get an understanding of the relevant traffic to the domain name.

Here the role of Uniregistry (GoDaddy) is less that of registrar and more that as a provider of monetization services to customers who wish to monetize traffic to their domain names.

Context matters. It is within the context of the Respondent choosing to monetize the domain name using a company that happens to offer both registrar and monetization services that the Panel’s holding is to be understood. Taken out of context, such a holding may be inapplicable.

We see this disregard for context in the <decathlons .org> dispute. The Complainant in <decathlons .org> cites to the baringsuk.com dispute from 2020. The Panel in <baringsuk .com> implicitly imputed responsibility for the links on the parking page to the Respondent, finding:

The Complainant also proved that the Respondent is using the Disputed Domain Name to lead to a hosting parking page, with commercial links. These facts confirm that the Disputed Domain Name is used to intentionally attempt to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to the Respondent’s website, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or endorsement of the Respondent’s website.

Yet the facts in the <baringsuk .com> and <decathlons .org> disputes are quite different such that a holding in one dispute may have little relevance to the other dispute. For one, it is unclear from the holding in <baringsuk .com> whether the parking page is intentionally being monetized by the Respondent as in the <airsculpting .com> dispute above, or whether the links were supplied by default by the registrar, as in the <decathlons .org> dispute. For another, the UK-based Barings mark is so distinctive that it is not possible to conceive of a plausible legitimate commercial use for the <baringsuk .com> domain name that would not infringe on Barings rights, such that it is not the use but the registration itself that confirms the bad faith. Even in the absence of use, per Telstra, a finding of bad faith would still be justified.

This is in contrast to the facts in the <decathlons .org> dispute, for “decathlons” is a non-distinctive, widely used, dictionary word, ”, such that it is plausible to conceive of other legitimate, non-infringing, commercial uses for the domain name. The circumstances of the <baringsuk .com> dispute, therefore, do not serve as useful precedent for the <decathlons .org> dispute.

Where the facts are different, the holdings are different. In the comteam.biz dispute from 2007, Panelist Tony Willoughby found that the Complainant’s “COMTEAM” mark was not highly distinctive:

Accordingly, it is not of itself a trademark that is only sensibly referable to one party, the Complainant.

Willoughby found that the Respondent is not responsible for the content on the registrar provided parking page:

It appears to have been used solely to default to a parking page of the Registrar. The Complainant asserts that the Respondent has been earning revenue via the advertising links on the site. The Respondent acknowledges that the Registrar may have been earning money via those links, but denies that he has earned anything. The Panel is inclined in the circumstances to accept the Respondent’s denial on this point.

In another 2007 case, the genericxenical.net dispute, Panelist W. Scott Blackmer helpfully explores the relationship between attributing bad faith due to a registrar provided parking page and attributing bad faith due to the distinctiveness of the Complainant’s mark:

The Respondent denied obtaining commercial gain from a similar parking website. This is not entirely implausible, since the Panel is aware that some registrars temporarily “park” new domain names at websites with sponsored advertising links, without automatically sharing the click-through advertising revenues with the owner of the domain name unless and until the owner makes further arrangements…

Even assuming (charitably) that the Respondent has not yet recognized any commercial gain from the Domain Name, it is hard to imagine any other intention in registering a domain name confusingly similar to the Complainant’s fanciful, well-established trademark.

Blackmer found bad faith in this dispute not due to the content on the registrar provided landing page, but that, like in Telstra, the mark is distinctive and well-known such that it is not possible to imagine any plausible legitimate use for the mark:

Here, as in Telstra, the Complainant’s mark is distinctive and well known, the Respondent has not come forward with a legitimate reason for registering the Domain Name, and it is difficult to conceive of a good-faith reason to select the Domain Name, precisely because of the fame and distinctiveness of the mark.

The holdings in these various disputes suggest that the degree of distinctiveness of the Complainant’s mark is the primary determinant of bad faith, not the content appearing on a registrar supplied default landing page.

Panelist Jeffrey Neuman, whose background includes high level positions at registries, is familiar with how registrar provided landing pages work and is sensitive to the problem of inapplicable citations. In his recent decision ordering the transfer of the meta-statefarm.com domain name he made sure to clarify that he was not attributing bad faith to the Respondent due to the registrar provided landing pages (emphasis added):

However, the Panel agrees here with the Respondent – namely that registrants, especially those that do not buy or sell domain names for a living, should not be held responsible for parking pages that are stood up by default by its domain name registrar, especially where registrants derive no financial or other benefit from the content or links contained on the website other than letting others know that the domain name has been registered. The Panel notes that it is an unfortunate common practice of registrars to place advertising on the landing pages of its customers’ domain name where its customers have not published any content of its own on the domain. Most registrants are likely unaware of this practice and like the Respondent receive no benefit, financial or otherwise, from such a landing page. Nor are most registrants aware that they can change their settings at a registrar to not allow this to happen. It would be unfair to hold registrants that are unaware of this practice accountable for the actions of its registrar.

Neuman bases the transfer of <meta-statefarm .com> domain name on the fame of the marks and the implausibility of any good faith use. Although he accepts the Complainant’s transfer request, he states that he does not accept the Complainant’s allegation that because the domain name goes to “a page with third-party competing pay-per-click links” that this is evidence of bad faith use on the part of the Respondent. Instead, he goes to some effort to explain why doing so would be “unfair” since in general registrants “should not be held responsible for parking pages that are stood up by default by its domain name registrar”.

>> Comment Continues here

What’s the Difference Between a Registrant and a Privacy Service?

Markel Corporation v. DAS Legacy, NAF Claim Number: FA2304002041740

<MarkelGroup .com>

Panelist: Mr. Alan L. Limbury

Brief Facts: The Complainant provides a variety of insurance and financial services. It owns rights in the MARKEL mark through trademark registrations, including with the USPTO. On April 3, 2023, the Complainant filed an application with the USPTO on intent to use for the mark MARKEL GROUP. The Respondent registered the domain name in September 2011, however, did not put any content there.

According to the Complainant, since its registration, the domain name has not resolved to an active website but the Respondent’s phone number contained in the malware analysis report annexed to the Complaint is the same as the number used by the registrants of two other domain names associated with ransomware. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent appears to be using the site for commercial gain to negotiate a purchase and an unreasonable demand for payment. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The disputed Domain Name was registered on September 22, 2011, prior to the Complainant’s registration of its MARKEL word mark but many years after the registration of the Complainant’s MARKEL design plus word mark. As regards Complainants’ allegations in relation to malware, the Panel finds that the phone number and address attributed to the Respondent in the malware analysis report differs from the phone number and address of the Respondent provided by the Registrar to Forum in this proceeding. There is no evidence that the phone number and address provided by the Registrar are associated with ransomware actors nor that the domain name has been used in relation to malware or ransomware. Accordingly, the Panel is not persuaded that the Respondent is associated with ransomware actors.

As to the Complainant’s assertion of bad faith on the ground that the Respondent appears to be using the site for commercial gain by an attempt to negotiate a purchase and an unreasonable demand for payment, the Complainant provides no evidence of the attempted negotiation or of the amount demanded. Accordingly, the Panel is not satisfied that the Respondent registered or acquired the domain name in 2011 primarily for the purpose of selling, renting or otherwise transferring the domain name registration to the Complainant. There are no other possible grounds alleged for a finding of bad faith on the part of the Respondent. For these reasons, the Panel is not satisfied that the domain name was registered and is being used in bad faith.

RDNH: Such a finding is justified only in rare cases, such as instances where a complainant proceeds despite the fact that it knew or should have known that it did not have a colorable claim under the Policy. The phone number and address in Iceland attributed to the Respondent relied upon in the Complaint filed on April 26th 2023 were those contained in the annexed malware report’s WHOIS. The complainant was made aware of the Respondent’s different actual name, phone number and address in Florida upon receipt of the Registrar’s verification and the Complainant included those details in the header of the Amended Complaint. Despite this, the Complainant continued to assert that the Respondent’s phone number is the same as that associated with ransomware actors.

These circumstances satisfy the Panel that the Complainant filed the Amended Complaint knowing that the Respondent is not associated with ransomware actors and did so in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Special Guest Case Comment by Panelist, Igor Motsnyi: Igor Motsnyi is an IP consultant and partner at Motsnyi Legal. Igor is a UDRP Panelist with the Czech Arbitration Court (CAC) and the ADNDRC, and is a URS examiner at MFSD, Milan, Italy. Igor has been the Panelist in over 40 UDRP cases. The views expressed herein are Igor’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the ICA or its Editors. Igor is not affiliated with the ICA.

…

I find this decision notable for the two reasons:

- Complainant’s wrong reliance on the “malware” argument and

- Panel’s RDNH finding.

1. Complainant in <markelgroup. com> tried to establish Respondent’s bad faith by claiming that a malware analysis report “shows two of the domain names held by Respondent containing malware. The report shows that the domain name is tied to ransomware activities and the phone number that is publicly associated with the registrant on WHOIS of the <markelgroup. com> domain name has a history of being used by ransomware threat actors…”.

What was wrong about this argument is that the registrant’s WHOIS referred to by Complainant was not Respondent’s WHOIS but rather the Privacy Service in Iceland.

The Respondent’s identity was revealed by the registrar after the complaint was filed and the Panel noted that “Complainant was made aware of Respondent’s different actual name, phone number and address upon receipt of the Registrar’s verification and Complainant included those details in the header of the Amended Complaint. Despite this, Complainant continued to assert that Respondent’s phone number is the same as that associated with ransomware actors”.

This was clearly a wrong path for Complainant.

Complainant in <markelgroup. com> was internally represented by presumably its own employee (who may not be familiar with the Policy and may not even be a lawyer).

In <alfaleads. com>, WIPO Case No. D2019-3089 (see here), Complainant was professionally represented by a law firm yet made the same mistake of confusing the Privacy Service with Respondent and alleged bad faith on a basis of the fact that “Respondent “Perfect Privacy LLC” is well known as a professional cybersquatter” and “when Respondent “Perfect Privacy LLC” was notified of the Complaint, it decided to transfer the disputed domain name” to another respondent.

Complainants/their counsel in the UDRP proceedings should be able to make a distinction between any contact information associated with a particular privacy service and contact information of the actual respondent.

2. The second notable aspect of this decision, in my view, is Panel’s finding of RDNH. Respondent did not ask for RDNH and this was a default case. Besides, as noted above, Complainant was internally represented and some UDRP panels are reluctant to find RDNH in cases of unrepresented complainants.

Nevertheless, the Forum panelist in this case found that “Complainant filed the Amended Complaint knowing that Respondent is not associated with ransomware actors and did so in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking”.

This is in contrast to the < alfaleads. com> decision where the transfer was denied but RDNH was not considered by the WIPO Panelist or a more recent Forum decision in <thechosentv. com> (see here) where the Panel considered RDNH but declined to find it since “Respondent did not reply, Respondent did not incur any costs in the instant proceedings”.

It remains to be seen how UDRP jurisprudence will further develop in respect of RDNH. I would expect that the divide between the panelists will remain.

However, I would note that RDNH, while arguably a “toothless weapon”, has its own significance reflected in the history of the UDRP (see e.g. “Second Staff Report on Implementation Documents for the Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy” or “ICANN Second Staff Report”, par. 4.3: “The dispute policy should seek to define and minimize reverse domain name hijacking”).

Besides, RDNH, in my opinion, plays an important role in maintaining the original purpose of the Policy (“fighting abusive registrations”), educating the parties and stakeholders and hopefully preventing complainants/their counsel from filing wrong complaints in future.

Proving Bad Faith When the Registration Date is Unknown

Come and See Foundation, Inc. v. Nanci Nette, NAF Claim Number: FA2304002040469

<theChosenTV .com>

Panelist: Mr. Richard Hill

Brief Facts: The Complainant markets THE CHOSEN, an American religious historical drama series that premiered on December 24, 2017, via Internet streaming. As of January 3, 2023, the Complainant has 1.86 million subscribers to THE CHOSEN YouTube Channel and other social media presence. The Complainant incorporates its mark, THE CHOSEN in the domain name <thechosen .tv> and asserts rights in THE CHOSEN mark through its registration in the United States (filing date April 21, 2020; registration date September 7, 2021; first use in commerce date December 1, 2017). The disputed Domain Name was registered in 2011 and resolves to a website displaying third party pay-per-click advertising hyperlinks.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not use the disputed Domain Name for a bona fide offering of goods or services or a legitimate non-commercial or fair use and that the Respondent has registered the disputed Domain Name for the purpose of selling it to the Complainant [emphasis in original] who is the owner of the trademark THE CHOSEN or to a competitor of the Complainant for valuable consideration in excess of the respondent’s out of pocket costs directly related to the domain name. When contacted about selling the Domain Name, Respondent offered it for sale for $25,000. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The Complainant claims use since 2017, while the disputed Domain Name was registered in 2011. The Policy requires a showing of bad faith registration and use. In terms of section 3.8.1 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, where a respondent registers a domain name before the complainant’s trademark rights accrue, panels will not normally find bad faith on the part of the respondent except pursuant to Section 3.8.2, i.e. when the domain name was registered in anticipation of trademark rights. The Complainant does allege that such is the case here, however, the Complainant does not explain how the Respondent could possibly have anticipated, in 2011, that the Complainant would produce a TV series in 2017. Nor does it present any evidence to show that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in order to sell it to the Complainant. The Panel may deny relief where a complaint contains mere conclusory or unsubstantiated arguments.

The Panel conducted factual research regarding the disputed Domain Name by searching the Internet Archive, and also searched the Internet to see if there was a novel or an item for the year 2011, and it found, among others, a reference to a short film ‘The Chosen’ made in 2011. The Panel is of the view that it may be the case that the disputed Domain Name was registered in 2011 to promote the cited short film. Further, the Complainant does not allege that the disputed Domain Name changed hands since its original registration in 2011. Consequently, it assumes and the Panel must find, that the disputed Domain Name was registered by the current registrant well before the Complainant acquired its trademark rights. Thus there was no intent to target the Complainant and the disputed Domain Name was registered in bad faith. Also, there is no evidence to show that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name with the intent of selling it to the Complainant. Thus the Panel cannot find bad faith use under the Policy. For all the above reasons, the Panel finds that the Complainant has failed to satisfy its burden of proof for this element of the Policy.

RDNH: The Complainant, or its counsel, should have known that its Complaint, as presented, could not succeed, for the reasons set forth above. However, there is nothing in the record to indicate that the Complainant harassed the Respondent or that it acted with malice aforethought – as opposed to mere lack of knowledge of the Policy. Since the Respondent did not reply, the Respondent did not incur any costs in the instant proceedings. Thus the Panel declines to find the Reverse Domain Name Hijacking.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Anthony J. Biller of Envisage Law, North Carolina, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Comment by General Counsel Zak Muscovitch: Every case requires some investigation by counsel. This goes for complainants as well as respondents. For complainants, the investigation will generally focus on the Respondent and in some cases, the Respondent’s registration date.

When the Respondent’s registration date is unknown and the Creation Date is prior to the Complainant’s trademark rights, Complainant’s counsel will have to look for evidence to try and show that the Respondent more recently registered the Domain Name, i.e. it changed hands since the original creation by a third party. Historical Whois information concealed by privacy protection may make this difficult in some cases. Nevertheless, some evidence is still required. In the present case, Panelist Richard Hill found that the Complainant failed to provide that evidence: “Complainant does not allege – much less provide evidence to show – that the disputed domain name was transferred from the original registrant to some other entity”. This is unsatisfactory and proved fatal for the Complainant in this case. I previously wrote about this issue in Digest Volume 2.35 where I commented on the Neometals case and the kind of evidence that may be required in order to overcome an unhelpful Creation Date.

Had the Complainant undertaken the required investigation of its case, it may have been able to provide the requisite evidence to overcome the early Creation Date. For instance, a DomainTools report would have shown that although the Domain Name’s registrant was under privacy protection since it was created in 2011, the Domain Name apparently changed nameservers, changed privacy protection services, and changed registrar in 2019. The 2019 nameserver change was to Parklogic, suggesting a possible intentional change to PPC ads arranged by the registrant itself rather than a registrar landing page. This appears to be corroborated by Archive .org which shows that until around 2018 or 2019, the Domain Name resolved to a website belonging to movie production company called, Aris Pictures, which may have been associated with the 2011 short film called, The Chosen that the Panelist uncovered. Lastly, it appears from the registration records that the Domain Name may have expired and been subsequently picked up at the time that the Domain Name changed registrars. Collectively, this is fairly compelling circumstantial evidence that a change of registrant occurred in 2019, i.e. subsequent to the creation of the Domain Name in 2011 and subsequent to the establishment of the Complainant’s trademark rights

This circumstantial evidence, had it been uncovered by the Complainant may have been sufficient for the Panelist to draw an inference of the registration date, but would have been even more compelling had the Complainant also investigated the named Complainant herself. A search of UDRP.tools shows the Respondent has lost over 50 previous UDRP cases going back to 2015, making it more likely that the Respondent did not register it in good faith because of the 2011 film.

Nevertheless, without any such evidence, the Panel had no choice but to dismiss the Complaint as it correctly did, stating that in the absence of evidence, “the Panel must assume that the original registrant is the current registrant”.

Regarding the Panelist’s consideration of RDNH, it is commendable that the Panelist even considered this issue as some Panelists forget or decline to consider RDNH, especially in no-response cases, even though the Rules require the Panel to when the circumstances warrant. I have previously written in Digest 2.37 about Rule 15(e) and the obligation of Panelists to make an RDNH finding where warranted. The Panelist in this case considered whether RDNH was warranted, as was his obligation, and then ultimately decided in his discretion that it was not an appropriate case for RDNH. Given what we now know from the research that I included above, this ultimately turned out to probably be the right decision since the evidence seems to indicate that this was likely a case of cybersquatting even though the Complainant failed to provide the required evidence.

Notably, in considering RDNH, the Panelist stated in his reasons, the “Complainant, or its counsel, should have known that its Complaint, as presented, could not succeed” [emphasis added]. This is an indication that the Panelist was clued into possibility that despite the Complainant’s lack of evidence, the Respondent may have been a cybersquatter and a properly presented case may have exposed this. It is also important to appreciate the distinction between a finding that a case “should never have been brought” (which frequently attracts RDNH findings and rightfully so), and what the Panelist actually found in this case, which is that this “Complaint, as presented, could not succeed”. The latter considers that the Complaint suffered from an evidentiary shortfall that it pays for by losing its case, whereas the former concludes that ‘no matter what’, the Complaint was meritless and is therefore abusive and deserving of an RDNH declaration. This distinction provides a possible explanation for why the Panelist declined to find RDNH despite acknowledging that the Complainant or its counsel ought to have known that the Complainant was inadequate had they been more familiar with the UDRP or paid more attention. Inadequacy is a markedly different circumstance than bringing a case that can never be adequate because the theory of the case or the evidence runs contrary to the UDRP itself. It is the latter circumstance which justifies an RDNH finding in particular.

In this case however, the Complainant’s counsel had two previous UDRP cases under his belt and is an experienced lawyer that works on IP matters. As such, unfamiliarity with the Policy shouldn’t really be an excuse for commencing a proceeding against a Domain Name without any allegation or evidence that its registration post-dated the Complainant’s trademark rights. Nevertheless, I do however take the Panelist’s point that despite that, this case does not smack of an ill-intention of the Complainant so much as a bungle that the Complainant itself will pay for and needs no additional sanction in the form of RDNH, particularly since as it turns out the Complainant may have very well been right about the Respondent being a cybersquatter. Nevertheless, I do respectfully disagree that since “Respondent did not incur any costs in the instant proceedings” is a basis for not finding RDNH. Indeed, in some no-response cases it is even more warranted that RDNH be found, such as where a Complainant’s misleading arguments or baseless Complaint might have resulted in a transfer had not a vigilant Panelist prevented it. Although RDNH is not often improperly denied on the basis of “the Respondent not having incurred costs”, we did unfortunately see another instance of this recently which we wrote about in Digest Vol. 3.17. There, the Panelist inexplicably denied RDNH on the basis of “no trouble or expense” even though the Respondent had hired a lawyer to defend itself.

Ultimately however, in the particular case at hand, I think that the Panelist’s primary reason for denying RDNH had to do with the nature of the case – which an experienced Panelist such as this one, would have had a good nose for, even if the entire explanation wasn’t included in the decision. In other words, this wasn’t a case that shouldn’t have been brought – it was a case which should have been brought but in a much better manner. Indeed the Panelist said as much when he stated that the Complainant should have known that this case “as presented could not succeed”. The costs issue was clearly a secondary consideration and the absence of a Respondent’s costs in defending should never be a reason for denying RDNH. But in this particular case, I believe what the Panel was trying to express, was that given that the Complaint’s failure was due to how it presented its case (and in particular the lack of supporting evidence which resulted in its dismissal on a crucial, but technical basis), that RDNH wasn’t warranted, but had the Respondent responded, then RDNH might have been warranted because the Respondent would have been put through the trouble and expense of defending against a case that was meritless as presented. As things stood however, the Respondent wasn’t prejudiced as a result of this and may even have gotten away with something.

Not a Painless Experience for the owner of Painless .com, once put to Descriptive Use

Benco Dental Supply Co. v. Pain Management, Inc., NAF Claim Number: FA2305002043044

<painless .com>

Panelist: Mr. Steven M. Levy, Esq

Brief Facts: The Complainant offers retail services for dental supplies, equipment and medicaments and computer software for ordering such products. The Complainant owns rights in the trademark PAINLESS through its use in commerce since December 1, 1994, and its two registrations with the USPTO (earliest registered on March 25, 1997). The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 9, 1996, and currently resolves to a parked webpage hosting pay-per-click third-party links including some that lead to dental-related businesses. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name, with actual knowledge of the Complainant’s rights in the PAINLESS mark, in order to disrupt the Complainant’s business and divert customers for commercial gain.

The Respondent contends that the disputed Domain Name comprises a common dictionary word and before any notice of the present dispute, the Respondent used the disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of medical services, specifically interventional pain management, unrelated to the Complainant’s business. The Respondent further contends that its registration of the disputed Domain Name predates the USPTO registration date of the Complainant’s PAINLESS trademark and it is the Registrar, not the Respondent that operates the pay-per-click links that appear at the <painless .com> webpage.

Held: The Respondent submits an archived screenshot for the website at the disputed Domain Name, dated May 18, 2001, which seems to indicate that the Respondent was making a bona fide offering of services under the disputed Domain Name in 2001. However, the Respondent does not provide evidence that its medical practice continues to exist as of the date on which the Complaint was filed; the Panel must consider whether any more recent and different use is made of the disputed Domain Name. There is limited evidence that the Respondent uses the disputed domain name to display certain pay-per-click links relating to the Complainant’s field of dentistry, the Panel considers this insufficient to overcome the “preponderance of the evidence” burden which the Complainant must meet to prove that the Respondent is targeting its trademark. The word “painless” is, in the present context, a descriptive term and the Respondent’s name in the WHOIS record, Pain Management, Inc., does bear some relationship to this word. Further, most of the pay-per-click links reviewed by the Panel relate to the descriptive meaning of the word “painless” and the hosting of such a website is not illegitimate.

Although panels have not generally regarded constructive notice to be sufficient grounds upon which to base knowledge of a mark, it may be so where both the parties are subject to a jurisdiction that applies this legal concept, such as the United States of America. However, it is noted that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name prior to the registration date of the Complainant’s earliest USPTO trademark registration. Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii) is stated in the conjunctive (“registered and is being used in bad faith”) and the Panel finds that there is insufficient evidence upon which to conclude that the Complainant’s mark was highly distinctive or well-known, or that the Respondent knew of or specifically targeted the mark in 1996. Thus, the Panel finds, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the disputed Domain Name was not registered in bad faith. Further, there is insufficient evidence of the reputation of the Complainant’s PAINLESS trademark and the Respondent’s present use of the disputed Domain Name appears to be for the descriptive qualities of the word “painless”. As such, the Panel cannot conclude that the Respondent’s use of the disputed Domain Name is in bad faith under Policy.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Erica Goven, Nebraska, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Keith A. Wagner, Nebraska, USA

Website Changed After Filing Complaint

Shopify Inc. v. Michael Cao, CIIDRC Case Number: 20836-UDRP

<Shopify-Analytics .com>

Panelist: Mr. Zak Muscovitch

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 2004, is a publicly-traded company on the New York Stock Exchange with a market capitalization of over $39 billion dollars and 7000 employees as of September 21, 2022. It offers a cloud-based e-commerce platform used by online merchants through various websites, including those accessible through the domains, <shopify .com> and <shopify .ca>. The Complainant owns dozens of trademarks registered around the world including, a Canadian Trademark (registered January 18, 2011) and a United States Trademark (registered August 31, 2010). The disputed Domain Name was registered by the Respondent on March 29, 2023. The Complainant notes that “Shopify” is an invented word and states that accordingly, “Shopify” is not a word that traders would legitimately choose unless seeking to create an impression of association with the Complainant and that the last portion of the disputed Domain Name, “-analytics” is merely a descriptive word and does not add any distinctiveness to the disputed Domain Name.

The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Name is used for a website purporting to provide “Shopify Analytics” services to Shopify shop owners in the nature of messaging services to contact customers and the Complainant provides a copy of the said website. The website does not include the Complainant’s logo but contains a heading stating, “Why Shopify Analytics?” and contains a footer stating “Built by Shopify-Analytics, LLC”. The look and feel of the website are minimally related to the Complainant’s own website in that both generally use a green and black colour scheme to some extent, but it does not appear that the Respondent’s website attempts to visually mimic or pass itself off as that of the Complainant’s. The website does, however, contain some rather strange content, such as references to “Taxonomy” which is presented as an apparent brand name of certain open-source software with its code “available on GitHub”. The Respondent did not respond to the Complaint.

The Panelist exercised its discretion to review the live website associated with the Domain Name on the Internet in order to confirm its existence and nature. Notably, the website that is now associated with the Domain Name as of the date of within decision, is not the same website as included as an exhibit to the Complaint. Rather, it is a completely different website that makes no reference to SHOPIFY whatsoever and instead references “TaxPal” bookkeeping software. The links on the website such as “sign in”, “get started”, and “pricing” are non-functional. The Panelist, however, does not rely upon this second website as evidence in this proceeding as it does not form part of the Complaint delivered to the Respondent and in any event is unnecessary to satisfactorily resolve this matter.

Held: Given that the Complainant’s SHOPIFY trademark is well-known, highly distinctive and solely associated with the Complainant, the Respondent was very likely aware of the Complainant’s SHOPIFY trademark when it registered the Domain Name without the Complainant’s authorization. Moreover, the Respondent’s addition of “-analytics” to the Complainant’s trademark in the disputed Domain Name, shows a likelihood that the Respondent was also aware of the Complainant’s business since analytics are very much part of the platform that the Complainant provides. The fact that the Respondent put the Domain Name to use in connection with a website that appears to not even purport to provide SHOPIFY analytics-related services, but rather some kind of customer monitoring and chatting software (to the extent that this is even a genuine business offering rather than a fake website altogether, which is unclear), is a sufficient indication that the Respondent’s use is not for a bona fide business but rather, is improperly trying to drive traffic to his website based upon the goodwill and reputation of the Complainant’s trademark.

There is no question that given the highly distinctive nature of the Complainant’s SHOPIFY trademark combined with the descriptive term, “analytics”, which is associated with the Complainant’s services, the Respondent was aware of the Complainant at the time that he registered the Domain Name and purposefully targeted the Complainant to take unfair advantage of its goodwill and reputation for the Respondent’s own business purposes. Accordingly, the Panelist finds that the Respondent registered the Domain Name in bad faith. The Panelist further finds that the Respondent’s use of the Domain Name in connection with a website which falsely represents some connection with the Complainant for the purposes of promoting the Respondent’s own business or at least for the purpose of driving traffic to the Respondent’s website based upon the Complainant’s goodwill and reputation constitutes bad faith use as understood under the Policy. Accordingly, the Complainant has made out both bad faith registration and bad faith use, both of which are required under the Policy.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Daniel Anthony of Smart & Biggar LLP

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response