How to Lose a UDRP Case

By Steven M. Levy, Esq.

After more than two decades, over one hundred thousand published decisions, and the numerous secondary sources that are available to guide parties, there are now many resources available to prevent the filing of deficient UDRP pleadings. Plus, brand owners only get one bite at using this expedited dispute resolution procedure since, absent exceptional circumstances and new evidence that was not available at the time of the original Complaint, refiling is typically not permitted.

It’s critical not to underestimate the UDRP by treating it as a check-the-box process. Although not as complex as court-based litigation, there are many nuanced issues and procedures that are often involved. And losing a case can have serious consequences for Representatives and their clients. Money is wasted on filing and legal fees and the reputation of the client’s and representative’s names can be tarnished since UDRP decisions are made public …continue reading here.

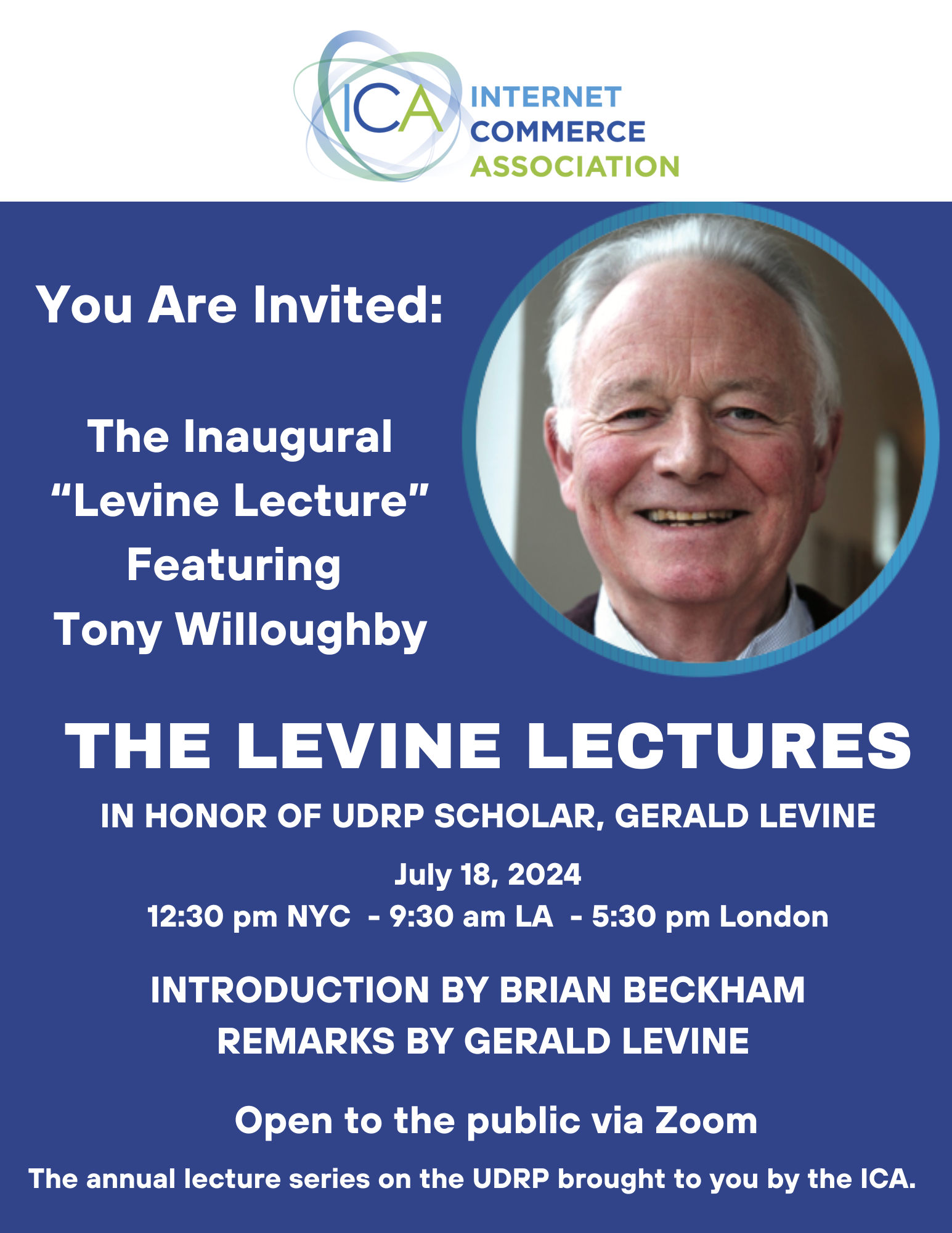

SIGN UP FOR THE INAUGURAL “LEVINE LECTURE” HERE

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.24), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Is a Trade Name Enough Under the Policy? (rocketship .com *with commentary)

‣ Does the Inclusion of an Additional Word, Change the Character of the Domain Name? (thelsatgenius .com *with commentary)

‣ “No Reasonable Way To Advertise My Services Without Mentioning LSAT” (masterlsat .com *with commentary)

‣ Registrant’s Right to use Well-known Mark in Domain Name (teslashop .com)

‣ Panel: Not Aware of Any Descriptive Meaning of Term ‘Trex’ (taxtrex .com)

Is a Trade Name Enough Under the Policy?

Rocketship AB v. ATTN Domain Inquiries, World Media Group, WIPO Case No. D2024-0698

<rocketship .com>

Panelists: Ms. Stephanie G. Hartung (Presiding), Mr. Jeffrey Neuman and Mr. Petter Rindforth

Brief Facts: The Swedish Complainant, active since 2018 is engaged in web development, app development, and managed hosting services. It owns the company name “Rocketship AB,” (registered on October 11, 2018) and domain names <rocketship .cloud>, <rocketship .nu>, and <rocketship .se>. The domain name <rocketship .se> is used as the primary marketing channel for the Complainant’s services. The Complainant claims that a Swedish-registered trade name can, according to national trademark law, constitute a hindrance to the registration of a trademark if there is a risk of the trademark being confusingly similar to the trade name. The US-based Respondent is engaged in the domain name investment business. The disputed Domain Name was registered in 1996 by Gerald Gorman, the owner and CEO of the Respondent. The disputed Domain Name was initially used to offer personalized email addresses and is currently resolved on a landing page with generic PPC links. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent’s website under the disputed Domain Name merely consists of different PPC links to potential competitors.

The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent has actively registered email addresses containing the first and last names of employees and the founder of the Complainant with the disputed Domain Name to commit fraud by ordering products in the name and billing address of the Complaint, therefore actively targeting the Complainant’s registered trade name which has achieved significance as a source identifier. The Respondent contends that the Complainant does not have enforceable trademark rights under the Policy, neither by virtue of its filing for a Swedish business name in 2014 nor as a common law trademark. The Google search results for “rocketship” show many third-party uses of the word in association with schools, businesses, data companies, mobile or web applications, entertainers and more – none of the results seem to show Complainant’s Swedish business and that there’s no possible way the Complainant can prove that the Respondent targeted the non-existent Complainant when it registered the disputed Domain Name in 1996, meaning more than 18 years before the Complainant was founded.

Held: It is evident that the Respondent has been operating, inter alia, a business of email hosting through the disputed Domain Name since 1996 when the Complainant neither existed nor was even about to become existing. There are no facts or other circumstances included in the Case File to disbelieve Respondent’s contentions that it purchased the disputed Domain Name in 1996 because it was an available, generic dictionary word gTLD “.com” domain name. Thus, it is reasonable to argue that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name based on its meaning as a common English dictionary word and not to target a specific trademark. Moreover, it also sounds reasonable, that the disputed Domain Name forms part of the Respondent’s consumer email business which includes hundreds of mail-related domain names, many of which are descriptive terms composed of common words combined with the terms “mail” or “post”; also, the Respondent creates and develops businesses combined with its portfolio of strong generic domain names, at times by founding the companies and building teams, and in other cases by forming partnership.

It should also be noted that the MX records activated under the disputed Domain Name point to the legitimate email service business of Mail .com, too. This Panel, thus, concludes that the primary purpose of the Respondent’s making use of the disputed Domain Name is bona fide within the meaning of paragraph 4(c)(i) of the Policy, thus constituting rights or legitimate interests therein. Finally, for the sake of completeness and in light of the Respondent’s request to find a case of RDNH, the Panel holds that the evidence submitted by the Parties does not indicate that the Respondent’s aim in registering the disputed Domain Name was to profit from or exploit Complainant’s ROCKETSHIP trade name; in particular, the Respondent did not register the disputed Domain Name in bad faith targeting the Complainant or its trade name rights because, undisputedly, the Complainant had no trademark rights at the time that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name.

RDNH: The facts in this case demonstrate that the Complainant knew or should have known that it could not succeed in demonstrating the registration and use of the disputed Domain Name in bad faith. The Complainant, represented by counsel, also did not disclose to the Panel in either its original filing, nor did it even acknowledge in its supplemental filing, that its allegations of the fraudulent email addresses had been responded to, and in fact, addressed by the Respondent and its email service provider. Yet, despite knowing Respondent’s service was being used by thousands of users for more than two decades, the Complainant continued to argue in its supplemental filing that the Respondent was “using the domain rocketship .com in bad faith to execute the act of fraud.” It needs to be emphasized that the UDRP is not intended to be a mechanism to address allegations of general fraud, but rather only in cases where a complainant can prove that the disputed Domain Name was both registered and used in bad faith.

The Complainant, represented by counsel, evidently knew or should have that this could not have been the case here, which is why bringing this UDRP Complaint constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding.

Concurring Opinion by Panelist, Jeffrey Neuman:

I wholeheartedly agree with the outcome of this case and the finding of the Reverse Domain Name Hijacking. However, I am not convinced that the Complainant has satisfied its burden of proof that it has standing to bring this action. More specifically, the Complainant has not demonstrated that it has trademark rights in the ROCKETSHIP mark. It is understood that the Complainant has a trade name under the Trademark Act of Sweden (“Act”). And that Act does state that a proprietor of a trade name has exclusive rights in the trade name as a trade symbol. However, the Act then states that “A party using his or her name as a trade symbol has exclusive rights in the symbol as a trade symbol; provided that the name is distinctive for the goods or services for which it is used.”

In this case, the Complainant concedes that it does not have a registered trademark with Sweden’s national trademark office. WIPO Overview Section 1.3 states that where a mark is not registered, to establish unregistered or common law trademark rights for purposes of the UDRP, the complainant must show that its mark has become a distinctive identifier which consumers associate with the complainant’s goods and/or services. The Complainant merely provided conclusory allegations of unregistered rights and did not provide any of the types of evidence identified in the WIPO Overview. Therefore, I believe that the Panel should not have found that the Complainant satisfied the first element of the UDRP.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: AWA Sweden AB, Sweden

Respondents’ Counsel: ESQwire.com PC, United States

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: My comments this week will have to be briefer than usual as I am still in Africa after attending ICANN80 in Kigali.

Attempted Withdrawal of the Complaint

My first observation is that a week after the Response was filed, the Complainant apparently requested that its Complaint be withdrawn. The Respondent however, did not agree and the Complainant then apparently maintained its request for transfer of the Domain Name and the Panel appropriately proceeded to a decision on the merits.

Withdrawing a Complaint after a Response is filed is not always permitted. Complainants sometimes want to withdraw their Complaint after receiving a Response which disproves a Complainant’s allegations of cybersquatting and requests a finding that the Complaint was brought in bad faith, i.e. Reverse Domain Name Hijacking. Respondents in such circumstances may want to see a Complaint proceed to a final determination on the merits and particularly on the request for a finding of RDNH. A Respondent may also want the case to proceed to determination on the merits where a Complainant purports to withdraw its Complaint but “without prejudice” – meaning that a Complainant could simply refile the Complaint at a later date.

Permitting a Complainant to simply withdraw a Complaint in such circumstances puts the Respondent to considerable effort and expense and can encourage Complainants to try their luck with an abusive Complaint, knowing that if they are called out for it by a defending Respondent, that they can simply withdraw and even try again later with no repercussions.

Where a Complainant requests termination and the Respondent objects after filing its Response, that will generally be a sufficient reason for the Panel to proceed to a decision, as the Panel rightly did in this particular case. In the same way as a Complainant is prima facie entitled to ask for a full decision so that its position is publicly vindicated, so is a Respondent. This is particularly so where the respondent has actively sought a finding of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking.

Rule 10(b) of the Rules, which states that a Panel shall treat the parties with equality and ensure that each is given a fair opportunity to present its case, supports this approach. The case law is clear that where a Response has been filed, a Respondent may have a valid objection to a unilateral Complainant request to terminate the proceedings, particularly where; a) the Complainant has not asked for termination with prejudice; b) where the Respondent desires an adjudication on the merits; and/or c) where the Respondent has requested a finding of RDNH.

Complainant Trade Name or Trade Mark Rights?

The UDRP requires trademark rights. It is well established that a mere corporate name registration or a mere trade name registration, by itself, is insufficient. Nor does local legislation providing for exclusive use of a corporate name or business name (or something similar to it) assist in transforming a corporate or business name into a trademark. Many jurisdictions have such laws but the UDRP still requires trademark rights rather than exclusive use of a corporate or business name for the Complainant to have standing. The key differentiator, as suggested by the Concurring Panelist, is distinctiveness. Under the UDRP, it is well established that a Complainant must prove common law trademark rights by demonstrating that consumers associate the Complainant’s goods or services with the mark. If Panels were to allow a mere trade name registration or to afford rights equivalent to trademark rights by operation of a particular trade name law, it would effectively gut the longstanding and more rigorous requirements for trademark rights under the UDRP.

This is an important point that the Concurring Panelist was quite right to draw attention to. I do however note that the majority of the Panel did not make a finding that the “Complainant satisfied the first element of the UDRP”. Rather, the majority of the Panel “in light of the findings set forth under Sections B and C below…decided to leave the first element open”. As such, they apparently made no finding one way or the other on this point. That may have been a prudent approach to economically avoid having to opine on whether Swedish law affords “the same or at least comparable status as a trademark” however, as also noted by the majority, the Complainant “has kept silent on whether or not its ROCKETSHIP trade name may have acquired secondary meaning”. Given that the Complainant apparently failed to prove common law trademark rights, I think that leaving open the first element was a generous, though understandable, solution for the majority. I similarly give credit to the Concurring Panelist for his approach which was to call out the failure to meet the requirements of the Policy.

Does the Inclusion of an Additional Word, Change the Character of the Domain Name?

Law School Admission Council, Inc. v. Bradley Yi, NAF Claim Number: FA2405002098364

<thelsatgenius .com>

Panelist: Mr. David S. Safran

Brief Facts: The Complainant claims rights in the LSAT marks and asserts that the disputed Domain Name incorporates its LSAT mark in its entirety and the words “the” and “genius” are merely generic terms that make the Domain Name even more confusingly similar. The Complainant also alleges that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the domain at issue because it was registered in the name of the owner of the domain and not a name corresponding to the domain name, while the website to which the domain resolves mentions the Complainant’s mark. Still further, the Complainant contends that the disputed Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith since it was registered with knowledge of the Complainant’s mark, the website to which the disputed Domain Name resolves creates a false association with the Complainant and passes off as the Complainant.

The Respondent contends that the disputed Domain Name is not confusingly similar to the Complainant’s marks because the word “genius” changes the whole impression of the domain from a test to a tutoring service. Additionally, the Respondent contends that it has rights and legitimate interests in association with its use of the domain to promote its tutoring services and the use of the LSAT mark in association with that is a fair use of the mark because it is necessary to enable consumers to know the nature of the tutoring service. Still further, the Respondent’s website to which the domain resolves does not create a false association with, or pass off as being the Complainant and the Complainant has failed to produce any evidence to support its contentions.

Held: The Panel finds that the Domain Name is not similar or confusingly similar to the Complainant’s marks because the addition of the word “genius” changes the character of the domain from referring to the LSAT test to a person able to successfully take the test. The Panel further finds that the Respondent offers a legitimate service distinct from the Complainant’s offerings. Further, the panel finds that the Respondent’s use of the LSAT mark is a “fair use” since it would otherwise be impossible to communicate consumers Respondent’s specialization in tutoring for the LSAT without mentioning “LSAT”. Thus, the Panel finds that the Respondent has rights and legitimate interests in the domain name <thelsatgenius .com>.

The Panel also finds that the Complainant has provided no evidence of bad faith actions by the Respondent. Thus, the Panel finds that the Complainant has failed to meet its burden of proof of bad faith registration and use under Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii). “Complainant makes conclusory allegations of bad faith but has adduced no specific evidence that warrants a holding that the Respondent proceeded in bad faith at the time it registered the disputed Domain Name. Mere assertions of bad faith, even when made on multiple grounds, do not prove bad faith.” [See Tristar Products, Inc. v. Domain Administrator / Telebrands, Corp., FA 1597388 (Forum Feb. 16, 2015)].

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Wendy K. Marsh of Nyemaster Goode, P.C., Iowa, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Avraham S.Z. Cohn, Massachusetts, USA

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

For a while now we have lamented the depreciation by some Panels of the first element of the three-part UDRP test. Yes, it is a “standing requirement” but that does not mean that it is a lesser requirement than the other two parts of the test, nor does it mean that Panels should routinely give Complainants an overly easy pass on the first part of test.

It is simply not always enough to meet the test of “identical or confusingly similar” on the basis that the trademark is visible within the disputed domain name. Para 1.7 of WIPO Overvioew 3.0, states: “… in cases where a domain name incorporates the entirety of a trademark… the domain name will normally be considered confusingly similar to that mark for purposes of UDRP standing.” Perhaps “normally” as in “most often” as is the case with descriptive terms added onto well-known and distinctive marks, such as VerizonShop .com, for example.

But not always, as was the case here. Here, the Panelist quite rightly found that the Domain Name is not identical nor confusingly similar to the Complainant’s mark, because the addition of the word “genius” changes the character of the domain name. Admittedly, the disputed Domain Name <theLSATGenius .com> contains the Complainant’s well-known mark LSAT in its entirety but that should not be the end of the inquiry. As the Panelist noted in comparing the instant case to a case involving NJtranshit .com, the addition of the word, “genius”, in this case “instantly tells the observer that the domain name is something quite different from the trademark and is intended to be different and to be understood to be different”. Can a domain name that incorporates a trademark in its entirety still be considered not confusingly similar? Certainly it can; How about “ThisIsDefinitlyNotTheOfficialPepsiWebsite – InsteadItIsMyOwnPersonalBlog .com”. Surely this domain name is not identical or confusingly similar with PEPSI even though the trademark is clearly visible within the domain name. On the other hand, perhaps recourse to the content of the website is required to make a solid determination of confusing similarity, as the Panelist did in this case.

Of course, there is also the approach shared by some other Panelists, wherein it is preferred to apply a very low threshold under the first part (basically, a “gimme”) and then decide the case under the second two elements. This is essentially the approach that was adopted by the Panelist in the MasterLSAT case below.

“No Reasonable Way To Advertise My Services Without Mentioning LSAT”

<masterlsat .com>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a not-for-profit organization that provides products and services that support candidates and schools through the law school admissions process. The Complainant asserts rights in the LSAT mark based upon use in connection with testing and test preparation course materials since 1948 and registration with the USPTO (January 10, 1978). The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not use the disputed Domain Name for any bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate non-commercial or fair use as seeks to pass itself off as affiliated or associated with the Complainant for the promotion of competing services. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent has attempted to disrupt the Complainant’s business and attract internet users to its sites for commercial gain by creating a likelihood of confusion as to the source or affiliation of its website.

In his brief Response, the Respondent contends on receipt of the Complaint he immediately got in touch with the Complainant, who responded that they “simply wanted to sign a licensing agreement with me to allow me to continue using the domain. We agreed on the terms and they agreed to send paperwork for signing. They also agreed to withdraw this complaint upon initiating our agreement. I am still willing to sign the agreement”. The Respondent further contends that if the agreement is not initiated, “I am contesting this domain name matter because my Domain Name makes no claim, explicit or implicit, to be affiliated with LSAC or any of its trademarks. Being that I am an LSAT tutor, there is simply no reasonable way to advertise my services without mentioning “LSAT” as part of my website.

Held: The Domain Name was registered in 2016 and resolves to a website where the Respondent, under the name MASTER LSAT or Nate Morris, offers private or group tutoring preparing students for the Law School Admission Test (LSAT). These services have been offered since 2013. While the website does not contain a disclaimer about authorization, it is clear that it offers independent LSAT tutoring services by Nate Morris. Contrary to the Complaint’s assertions, there is nothing on the Respondent’s Website suggesting an association with the Complainant. The website makes no claims of affiliation and no apparent use of the Complainant’s get-up or copyrighted material on the Respondent’s Website. The Panel accepts the Respondent’s submissions that there is simply no reasonable way to advertise its services as a private LSAT tutor without mentioning “LSAT” on the Respondent’s Website and that no reasonable consumer would interpret the mere reference to LSAT alone as affiliation with the Complainant.

The doctrine of nominative fair use, as applied in UDRP cases like Oki-Data, supports this use. The Panel is satisfied that the Respondent is making a bona fide offering of goods and services at the disputed Domain Name and is not seeking to pass off as the Complainant or as associated with the Complainant as there is nothing on the Respondent’s Website that suggests an affiliation with the Complainant. Further, the Respondent is not trying to corner the market in domain names to deprive the Complainant of the opportunity to reflect its mark in a domain name and there is no “bait and switch” at the Respondent’s Website; the Respondent offers services that are asserted to assist customers in “mastering the LSAT”. The Panel concludes that the Respondent operates a legitimate business and has not tried to take unfair advantage of the LSAT mark. Therefore, the Complainant has not demonstrated that the Respondent lacks rights or a legitimate interest in the disputed Domain Name.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Wendy K. Marsh of Nyemaster Goode, P.C., Iowa, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Three things stood out to me in this case. First was that the Respondent expressly offered to sign the license agreement proposed by the Complainant but was apparently rebuffed or ignored, thereby compelling the Panelist to proceed on the merits. The second that stood out to me was the plain and compelling explanation of the Respondent’s good faith use (aka “nominative fair use”) of the Domain Name: “here is simply no reasonable way to advertise my services without mentioning ‘LSAT’ as part of my website” This is the essence and basis for nominative fair use and reminds us of the logical and justifiable basis for this doctrine. The third thing that stood out to me was the Panelist’s thorough analysis and application of the doctrine of fair use, which is worth reading and bookmarking.

Registrant’s Right to use Well-known Mark in Domain Name

Tesla Inc. v. Korneliusz Wieteska / Zakupomania .pl Sp. z o.o., NAF Claim Number: FA2405002096260

<teslashop .com>

Panelist: Mr. Jeffrey M. Samuels

Brief Facts: The Complainant owns the trademark TESLA, which it has used since 2003 on a variety of vehicles, energy, battery and solar goods and services, battery and vehicle accessories, toys, clothing, and related lifestyle goods. It holds numerous trademark registrations globally, including in the EU and the US and also owns the domain name <tesla .com> and operates a webstore at <shoptesla .com>. The disputed Domain Name was registered by the Respondent on October 20, 2020. The Complainant alleges the disputed Domain Name is used to sell Tesla products or related items and to deceive consumers into giving personal and financial information. To the extent, the Respondent could be considered a reseller, the Complainant argues that the Respondent is not entitled to rely on the so-called Oki defense (WIPO Case No. D2001-0903), insofar as the website in issue does not include a disclaimer of affiliation with the Complainant.

The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent’s actions demonstrate bad faith, aiming to profit from Tesla’s goodwill by creating confusion about affiliation. The Respondent’s use of the TESLA mark, images, and a similar domain name misleads consumers and attempts to fraudulently gain commercial benefits. The Respondent contends the disputed Domain Name was registered for non-commercial purposes (features a family trip photo), specifically to connect with other electric car enthusiasts and share experiences related to electric cars, electromobility, and car parts. The Respondent further contends that the disputed Domain Name was registered in 2006, predating the earliest TESLA trademark registration in 2013. The Complainant operated under the name TESLA MOTORS until rebranding to TESLA in 2019.

Held: The Amended Complaint includes the website associated with the disputed Domain Name, in both the original Polish language and as translated by Google into English. The website invites the public to become a <telsashop .com> partner and indicates that “Together we will deliver parts and accessories for these great electrics around the world.” The website then invites the public “to propose cooperation with us or offer products or services and to contact us?” While the decision in Oki, referred to in the Amended Complaint, is not directly on point, the Panel finds the test outlined in Oki relevant to the instant dispute (See, e.g., Dr. Ing. H.c.F. Porsche AG v. Del Fabbro Laurent, WIPO Case No. D2004-0481, where the panel applied Oki where the respondent used, without authorization, the disputed Domain Name <porschebuy .com> in connection with a website that offers Porsche goods and services.)

It is certainly true that the disputed website does not, in the words of Oki, “accurately disclose the registrant’s relationship with the trademark owner.” However, in the opinion of the Panel, a fair and reasonable reading of the website would not, again in the words of Oki, “falsely suggest” that the Respondent is the trademark owner or that the website is the official site. Rather, the website’s discussion of the problems experienced by owners of TESLA cars, in particular the extremely expensive parts, and the Respondent’s stated desire to address this problem by creating a business to provide a platform “where every Tesla driver will find parts and accessories for their machine” would not necessarily lead one to conclude that the site is run by or authorized by the Complainant.

The overall tenor of the website could reasonably lead one to conclude that the site is run by the owner of a TESLA who is merely seeking to communicate with other TESLA owners regarding not only the benefits of ownership but also the problems associated with the cost of parts and accessories. While the disputed website includes a photo of a TESLA vehicle, the vehicle’s license plate supports the Respondent’s assertion that the photo on the website depicts a family trip. In sum, bearing in mind that the Complainant bears the burden of proof on all elements of the Policy, the Panel concludes that the Respondent has rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name. While the disputed site does not explicitly disclose the Respondent’s relationship with the Complainant, it does not falsely suggest such a relationship.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Sarah Alberstein of ArentFox Schiff LLP, District of Columbia, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Rafał Sikora, of SikoraLegal Rafał Sikora, Poland

Panel: Not Aware of Any Descriptive Meaning of Term ‘Trex’

ARDSIP Pty. Ltd v. Joseph Deacon, WIPO Case No. D2024-1207

<taxtrex .com>

Panelist: Mr. Adam Taylor

Brief Facts: Since July 2016, the Complainant has offered “R&D tax credit software” under the TAXTREX mark, initially via <taxtrexsoftware .com> and later at <taxtrex .online>. This software helps users comply with tax laws. The Complainant holds registered trademarks for TAXTREX in several countries, including the US trademark, filed on April 21, 2015, and registered on September 5, 2017. The Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name through a GoDaddy auction around September 5, 2016, where the Complainant was an unsuccessful bidder. On December 7, 2016, the Complainant contacted the Respondent to ask if they would sell the domain name, and the Respondent replied with USD $8,500. On September 8, 2017, the Complainant emailed again, offering USD $2,000 for the Domain Name and stating that it would have limited value to others since the Complainant owned the US trademark for TAXTREX.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent had failed to demonstrate any bona fide offering of goods or services or other legitimate interest. Rather the email communications between the parties demonstrate the Respondent’s “intention to extort money from the Complainant in exchange for the disputed domain [name]”. The Respondent contends that the Complainant’s trademark in the United States, was registered after the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name and that the disputed Domain Name incorporated two common descriptive words and happened to be offered for sale at an expired domain name auction. The Respondent also contends that it is providing a bona fide service and the Respondent’s willingness to sell its descriptive domain name in response to the Complainant’s enquiry is not evidence of bad faith as the sale of common descriptive domain names is, of itself, an acceptable practice and, moreover, it was the Complainant who initiated the purchase communications with the Respondent.

Held: The Respondent claimed that it acquired the disputed Domain Name because it comprised two common descriptive words, “tax” and “trex”. However, while “tax” is of course a dictionary term, the Panel is not aware of any descriptive meaning of the word “trex”. Even if so, the connection between this term and “tax” is far from obvious. Further, the disputed Domain Name has been used for a parking page with PPC links to goods/services. To the Panel, those PPC pages bear no obvious descriptive relationship to the disputed Domain Name. Accordingly, the Panel issued PO1 inviting the Respondent, firstly to identify the descriptive meaning that the Respondent attributes to “trex”; and to provide evidence that it had used the disputed Domain Name “in a manner that is legitimate and consistent with the descriptive meaning of the common terms”. The Respondent did not respond to PO1. In the Panel’s view, the Respondent’s use of the disputed Domain Name for the PPC links does not confer rights or legitimate interests.

However, the Complainant’s position is also unsatisfactory. It has provided no evidence indicating that the Respondent, which denies knowledge of the Complainant and is located in the United States, was likely to have been aware of the Complainant or its business, located in Australia, on acquisition of the disputed Domain Name. The Panel considers that this is a marginal case. In the Panel’s view, it is not inconceivable that the Respondent happened upon the disputed Domain Name in a list of expiring domains and selected it based at least on its quasi-descriptive nature (i.e., stemming from the word “tax”), independently of the Complainant. Overall, mindful that the burden of proof is on the Complainant, and notwithstanding the Respondent’s overdefensive approach, the Panel considers that, on balance, the Complainant has marginally failed to prove that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith by reference to the Complainant’s mark.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented