Panel: Complainant’s Representatives Likely Knew Case Bound to Fail

To the Panel’s credit, the dismissal and finding of RDNH was of course entirely justified as a result of the domain name registration preceding the Complainant’s trademark rights by 16 years. But why did the Respondent have to deal with a case this meritless? Yes, meritless cases are part and parcel of any field of law, including in civil courts and we have to live with them. Read commentary.

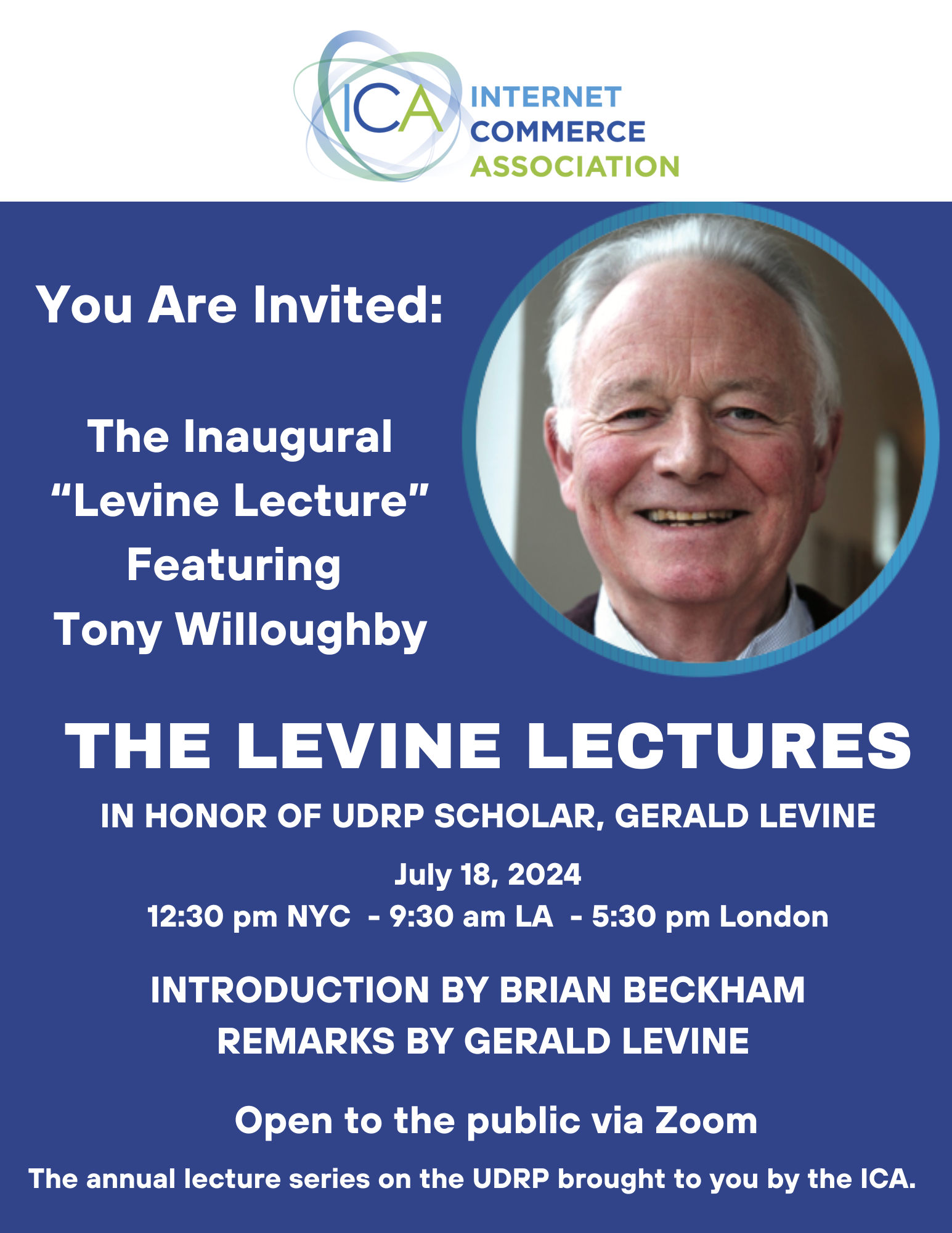

Last Call: Sign Up Now for FREE to Thursday’s Levine Lecture on Zoom:

SIGN UP FOR THE INAUGURAL “LEVINE LECTURE” HERE

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.28), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Panel: Complainant’s Representatives Likely Knew Case Bound to Fail (keylodge .com *with commentary)

‣ Domain Name Hijacked, Respondent Demands US $15k (sawnee .com *with commentary)

‣ Panel: ‘Impossible for Respondent to Have Registered Domain in Bad Faith’ (gigpig .com *with commentary)

‣ Domain Name ‘Transferred by Former Employee’ Without Authorization (paxful .com *with commentary)

‣ Complainant “Well Aware” of Respondent’s Long-term ‘Descon’ Business (desconllc .com *with commentary)

‣ Domain Name Subject of Concurrent Court Proceedings (alternativepods .com *with commentary)

Panel: Complainant’s Representatives Likely Knew Case Bound to Fail

Lotus SAS v. Domain is For Sale, Call 1-833-878-5115, WIPO Case No. D2024-1995

<keylodge .com>

Panelist: Mr. Adam Taylor

Brief Facts: The French Complainant is a property management company that has offered holiday rental intermediary services under the mark KEYLODGE since 2018. A company called Lotus Developpment SAS, owns a figurative French trade mark for KEYLODGE, filed on October 20, 2021, and registered on February 11, 2022. The Complainant operates a website at <keylodge .fr>. The disputed Domain Name was registered on April 13, 2000, and is listed for sale in various places including for USD 3,999 and USD 4,598.85. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent never used the disputed Domain Name and even the future use is likely to create a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s mark.

The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name “primarily for the purpose of selling, renting or otherwise transferring it”, which constitutes bad faith use and that the Respondent has engaged in a pattern of cybersquatting. On the other hand, the Respondent contends that the disputed Domain Name consists of two common words and is generic and descriptive. It was registered 21 years before the Complainant registered its trade mark in 2021 and the registration of such terms can be part of a legitimate business strategy. The Respondent further contends that the Complainant is guilty of reverse domain name hijacking as the 21-year temporal disparity indicates that the Complainant knew or should have known that it could not prove one of the essential UDRP elements.

Held: It is not disputed that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name in 2000, whereas the Complainant’s earliest claimed trade mark rights only arose in 2018. As the Complainant and its rights did not exist in 2000, the disputed Domain Name could not have been registered in bad faith. This is fatal to the Complainant’s case, irrespective of the nature of any later use of the disputed Domain Name because the Complainant must prove both registration and use in bad faith. Contrary to the Complainant’s claim, there is nothing objectionable about registering a domain name for sale in the absence of any intent to target the Complainant or a competitor, which could not have happened in this case as the Complainant did not exist in 2000. Similarly, none of the other Complainant’s arguments is relevant despite the Complainant’s assertions otherwise – non-use of the Domain Name; future use of may create the likelihood of confusion; Respondent used a privacy service; Respondent has engaged in a pattern of cybersquatting (as to which the Panel makes no finding).

RDNH: The Panel consider that factors articulated by panels for finding RDNH, as set out in section 4.16 of WIPO Overview 3.0, apply in this case. The Complaint acknowledges that the disputed Domain Name was registered in 2000. The Complaint adds that the disputed Domain Name was “updated” on January 11, 2023, but does not contend that the disputed Domain Name changed hands at that time. To the Panel, this unexplained reference to the “updated” date indicates that the Complainant’s representatives knew they were advancing on shaky ground. Furthermore, the Complaint contains many references to previous UDRP decisions, indicating that the Complainant’s representatives were likely familiar with established Policy precedent and that they therefore knew that their case was bound to fail. Based on the available record, the Panel finds that the Complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Coriolan, France

Respondents’ Counsel: Law Offices of Grant G. Carpenter, U.S

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: To the Panel’s credit, the dismissal and finding of RDNH was of course entirely justified as a result of the domain name registration preceding the Complainant’s trademark rights by 16 years. But why did the Respondent have to deal with a case this meritless? Yes, meritless cases are part and parcel of any field of law, including in civil courts and we have to live with them. But in civil courts, there are often severe sanctions for abuse of the court’s process, such as fines and even sanctions or disbarment. In the UDRP, we do not have any of that so we must wonder whether the lack of serious sanction is itself one of the reasons that parties – particularly those represented by counsel – believe that they can file abusive and meritless complainants with relative impunity, free from the threat of severe sanctions like what they would face in court systems for similar misconduct.

In the context of the UDRP, meritless and abusive proceedings are indeed relatively rare, with only 500 RDNH cases as of 2022, out of some 100,000 cases since 1999. But in absolute terms, that is not an insignificant number. 500 cases where a Complainant, usually represented by counsel, filed a meritless and abusive claim in order to get a coveted and often valuable domain name for itself from an innocent domain name owner. This is of course, cause for concern but what I wonder is why must a Respondent have to deal with such cases – at significant effort and expense – even if they are ultimately vindicated by a just Panel? We should seriously consider whether Providers should be required to provide a “blunt warning” to potential filers so that there is no question that they are aware of the obligation to not abuse the system and in particular, to alert them to the futility of filing a Complaint in respect of a domain name that was registered prior to trademark rights being acquired. Yes, we would still face Complaints filed by parties and lawyers who conscientiously abuse the system despite having received a blunt warning, but at least we might face fewer abusive Complaints and thereby lessen the chances of innocent domain name owners having to pay to respond to meritless and abusive Complaints.

Domain Name Hijacked, Respondent Demands US $15k

Sawnee EMC v. faris ALMALKI, WIPO Case No. D2024-2087

<sawnee .com>

Panelist: Mr. Assen Alexiev

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1938, is the eighth-largest electrical distribution cooperative in the United States, operating about 12,000 miles of distribution lines in seven counties. The Complainant is the owner of the United States trademark SAWNEE, registered on July 20, 1999. The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 2, 1996, by the Complainant and until recently used for the Complainant’s official website. According to the Complainant’s affidavit, on April 29, 2024, the ownership of the disputed Domain Name was transferred from the Complainant. On May 4, 2024, the Respondent offered to sell the disputed Domain Name to the Complainant for US $15,000. According to the Complainant, the fact that the Respondent reached out directly to the Complainant with an offer and pressed it to make a quick decision indicates that it was fully aware of the Complainant and its trademark and of the urgency that the hijacking of the disputed Domain Name had caused to the Complainant.

The Complainant adds that the Respondent used the Complainant’s Network Solutions account to change the access details to lock the Complainant out of its account and then threatened to auction the disputed Domain Name to a third party if the sum asked for was not paid immediately. The Complainant submits that its customers have been impacted severely because the Respondent’s actions caused the disruption of its billing portal at the disputed Domain Name and cut them off from important updates regarding the electricity of their homes and businesses. The Respondent did not formally reply to the Complainant’s contentions. With its informal communication to the Center on May 30, 2024, the Respondent only asked “What are you trying to do?”

Held: The factual allegations are supported by an affidavit issued by an employee of the Complainant and by printouts of the communication exchanges between the same employee and the Respondent. The Respondent does not dispute the contentions of the Complainant or the evidence submitted by it. Further, the Respondent does not provide any evidence that it has legitimately acquired the disputed Domain Name. Considering the above, the Panel concludes that the Complainant’s prima facie case that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name has not been rebutted.

Having reviewed the record, the Panel finds the Respondent’s registration and use of the disputed Domain Name constitutes bad faith under the Policy. The Complainant submits that the Respondent illegally transferred the disputed Domain Name to itself by hacking the Complainant’s account with the then registrar of the disputed Domain Name, and then approached the Complainant with a demand for payment of US $15,000 for its return to the Complainant. These allegations are supported by evidence and have not been disputed by the Respondent, which has not provided any plausible explanation or evidence as to how and why it acquired the disputed Domain Name and why its actions should be regarded as legitimate.

In the Panel’s view, the above supports a conclusion that the Respondent more likely than not illegally acquired control over the disputed Domain Name, targeting the Complainant in an attempt to receive financial gain by selling it back to the Complainant.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: ZeroFox, United States

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Domain name theft is not directly dealt with by the UDRP absent meeting the established three-part test. But where the three-part test is met, the UDRP can assist a Complainant who had its domain name stolen, as was the case here. Nevertheless, valuable domain names – particularly those actively used for an important business such as an electrical distribution system like the Complainant in this case – should not rely upon the UDRP to protect their domain name. Rather, it is important to consider what pre-emptive steps and precautions one may take to safeguard a domain name from theft. One such step and precaution is to employ a “registry lock”. Verisign, the operator of the .com gTLD, explains its service as follows:

“Registry-level locking of domain names provides additional levels of authentication between the registry and the registrar of the domain name. If an end customer requests a change to a Registry Locked domain name, an authorized individual at the registrar must submit a request to Verisign to unlock the domain name. This requester is then contacted by Verisign via phone and required to provide an individual security phrase in order for the domain name to be unlocked. This “out-of-band” step helps protect against automation errors and system compromises.”

Having served on the ICANN Transfer Policy Working Group, it became clear to me that although ICANN is able through policy and procedure, to assist in safeguarding domain names in some respects, overall, these policies and procedures should be considered minimum standards and therefore registrants may sometimes need to pay for greater protection, such as with a registry lock services or bespoke security services provided by a registrar.

Panel: ‘Impossible for Respondent to Have Registered Domain in Bad Faith’

GigPig Ltd v. Gigpig Inc, WIPO Case No. D2024-2003

<gigpig .com>

Panelist: Ms. Kathryn Lee

Brief Facts: The UK-based Complainant, incorporated in March 2022, operates a live music marketplace and platform at <gigpig .uk> that gives bookers and venue managers access to verified local artists to book and manage live music. The Complainant has a pending trademark application for the GIGPIG mark and two pending trademark applications for GIGPIG and Design, filed in the United Kingdom on February 14, 2024. The disputed Domain Name was registered on September 19, 2001, and resolves to a website displaying PPC links to terms such as “becken,” “birdy grey bridesmaid dresses,” and “drum kits.” The Complainant points out that the ownership of the disputed Domain Name changed from “Jinsoo Yoon” to “Gig Pig Inc.” in 2017 (while the email address remained the same) and that the individual “Jinsoo Lee” who is or is associated with the Respondent has engaged in a pattern of conduct, evidenced by the 25 or so UDRP decisions rendered against him involving domain names incorporating well-known marks.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name to unfairly capitalize on the Complainant’s up-and-coming trademark rights for GIGPIG, as the Complainant made preparations to launch the GigPig brand from 2012 to when the company was established in 2021. The Complainant further alleges that it contacted the Respondent, and the Respondent requested US $48,500 for the purchase of the disputed Domain Name, which is more than the Respondent’s documented out-of-pocket costs. The Respondent contends that it is a company named “Gigpig” which was established around 20 years ago, and that as the disputed Domain Name was registered in 2001, well before the Complainant was established in 2021, the Respondent did not have any bad faith intention in the registration or use of the disputed Domain Name.

Held: The presented evidence in the case file does not indicate that the Respondent’s aim in registering the disputed Domain Name was to profit from or exploit the Complainant’s trademark. The record shows that the disputed Domain Name was registered in 2001, while the Complainant was established in and commenced use of GIGPIG only in 2022. Therefore, the Respondent could not have registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith. The Complainant asserts that it started making preparations to launch the GigPig brand in 2012 and that there was a change of ownership of the disputed Domain Name in 2017, suggesting that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name to trade on the forthcoming fame and goodwill associated with the mark since it was aware of the Complainant’s plans to launch a business using GIGPIG.

However, the Complainant has not provided sufficient evidence to show the reputation of its predecessor/founder by the alleged time the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name, or how the Respondent would have been aware of the Complainant’s business plans. Rather, given that the email address for the domain name registrant remained the same before and after this supposed transfer, it would seem that there was no actual transfer of the disputed Domain Name. There is also no evidence of the use of the disputed Domain Name in bad faith. The price that the Respondent demands for the disputed Domain Name may be viewed as excessive, but an offer to sell a disputed Domain Name without additional supporting factors showing an intent to take advantage of a trademark does not necessarily indicate bad faith. See Section 3.1.1 of the WIPO Overview 3.0.

Finally, for the sake of completeness, while the Complainant argues a pattern of cybersquatting, every decision shall be based on its own merits, and here, the facts do not support a finding of registration and use in bad faith.

RDNH: Here, the disputed Domain Name was registered well before the Complainant even came into existence, so it would have been impossible for the Respondent to have registered the disputed Domain Name to target the Complainant and its “nascent” mark. The Complainant should surely have known that the Complaint could not succeed based on these facts, and proceeding with this Complaint can only be viewed as an attempt to deprive a registered domain-name holder of a domain name. Therefore, the Panel finds that the Complaint was brought in bad faith, in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking, and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: In my above comment on the keylodge case, I suggested that prospective Complainants be given a blunt warning to warn them off filing an abusive and meritless case such as where the domain name clearly predates the trademark right relied upon. Would such a blunt warning have worked here? In this case the Complainant was apparently not represented by a lawyer, so perhaps a blunt warning to the Complainant could have served to dissuade the Complainant from filing this woeful and abusive case. As the Panel noted:

“Here, the disputed domain name was registered well before the Complainant even came into existence, so it would have been impossible for the Respondent to have registered the disputed domain name to target the Complainant and its “nascent” mark. The Complainant should surely have known that the Complaint could not succeed based on these facts, and proceeding with this Complaint can only be viewed as an attempt to deprive a registered domain-name holder of a domain name.”

If the Complainant had been warned and still proceeded headlong, it would have made this an even clearer attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking, so either way, a blunt warning could have served an important purpose. Such RDNH cases are more often than not, brought by parties who are inexperienced with the UDRP and do not take the time to familiarize themselves with the case law and available guidance. That is their own fault and not an excuse. But the goal should be to avoid abusive Complaints in the first place, rather than penalize (in a rather weak fashion, mind you) Complainants after the fact as the latter does very little to assuage the harm and cost that an innocent Respondent must go through once a case is filed, even if they are ultimately “victorious”.

Domain Name ‘Transferred by Former Employee’ Without Authorization

Paxful Holdings, Inc. v. Eric Petters, NAF Claim Number: FA2406002101716

<paxful .com>

Panelist: Mr. David E. Sorkin

Brief Facts: The Complainant operates a cryptocurrency marketplace with more than 12 million customers around the world. The Complainant has used the PAXFUL mark in connection with its services since at least as early as 2015. The Complainant owns a United States trademark for PAXFUL in standard character form. The Complainant registered the disputed Domain Name <paxful .com> in 2015. In May 2024, the Complainant discovered that an unauthorized request to change the registrant contact details for the domain name had been made in January 2023 by a former employee of the Complainant who was later affiliated with one of the Complainant’s competitors. As a result, the Complainant was stripped of ownership and control of the domain name, although the domain name continues to point to the Complainant’s primary website. The Complainant asserts that the Respondent is not commonly known by the domain name, has no relationship with the Complainant, and is not authorized to use the Complainant’s mark. The Respondent failed to submit a Response in this proceeding.

Held: The Respondent does not appear to have made any active use of the domain name, apart from pointing or redirecting it to Complainant’s website. Such use does not give rise to rights or legitimate interests under the Policy. The Complainant has made a prima facie case that the Respondent lacks rights and legitimate interests in the Domain Name, and the Respondent has failed to come forward with any evidence of such rights or interests. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complainant has sustained its burden of proving that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed Domain Name.

The circumstances outlined in paragraph 4(b) are not exhaustive; the totality of the circumstances must be considered in the assessment of bad faith. The Complainant’s allegations, supported by evidence and unchallenged by the Respondent, are that the disputed Domain Name was appropriated from the Complainant by a former employee for the benefit of a competitor. Such circumstances are indicative of bad faith registration and use under the Policy. See, e.g., Four E, LLC v. Bin Qin / Submit11, FA 2070278 (Forum Dec. 5, 2023) (finding bad faith registration and use in similar circumstances); Scientific Specialties Service, Inc. v. Marc Grebow / PrivacyProtect .org, supra (same); Vladislav Soklakov v. Domain Admin, Whois Privacy Corp, D2015-0794 (WIPO July 20, 2015) (same); Skyline Windows, LLC v. skylinewindows .com Private Registrant, FA 1525647 (Forum Dec. 10, 2013) (same); Anbex Inc. v. WEB-Comm Technologies Group c/o Domain Hostmaster, FA 780236 (Forum Sept. 19, 2006) (same).

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Jason Rawnsley, United States

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: In my above comment on sawnee case, I suggested that registrants should consider a “registry lock” to help prevent domain name thefts. Would such a lock have prevented the unauthorized transfer in this case? Probably not, as registry locks seem to be most effective at preventing “stranger thefts”, i.e. hacking by an unknown party who is a stranger to the registrant. But where the alleged unauthorized transfer is effected by a former employee, one could assume that the former employee might have leveraged its privileged access to and familiarity with the Complainant’s security systems to perpetrate the theft, notwithstanding a registry lock. For instance, the former employee could have telephoned the registry to remove the registry lock if the former employee was originally the person in charge of the domain name to begin with and as such had they ‘key’ to unlock the domain name and falsely authorize its transfer even upon ceasing to be an employee.

Complainant “Well Aware” of Respondent’s Long-term ‘Descon’ Business

<desconllc .com>

Panelist: Mr. W. Scott Blackmer

Brief Facts: The Complainant is an engineering and consultancy company established in 1977 under the laws of Pakistan and subsidiaries established in UAE since 1984. The Complainant has numerous trademark registrations in several jurisdictions, including the DESCON (word) registered in Pakistan (March 18, 1980) and in UAE (April 3, 2012). The disputed Domain Name was created on February 7, 2002, and resolves to the Respondent’s website, offering system engineering, testing, and maintenance services for more than “two decades”. The Response includes a copy of a business license dated March 22, 1994, under the name “Descon Automation Control System”.

The Complainant alleges bad faith, as the Complainant’s mark was already established and in use, internationally and specifically in UAE, in the same line of business, when the Respondent registered and subsequently used the disputed Domain Name. The Complainant points to several projects in UAE in which the Complainant was involved from 1992-2000, as well as media articles in the UAE and worldwide, supporting the argument that the Respondent would necessarily be aware of the Complainant. The Complainant served a notice letter on the Respondent through court process on June 13, 2022, demanding that the Respondent cease using the Complainant’s DESCON mark and transfer the disputed Domain Name. The Parties met but did not agree to a transfer or a co-existence agreement.

The Respondent does not challenge the Complainant’s trademarks but argues that the Parties offer different services and have co-existed in UAE for decades, without customer confusion. The Respondent furnishes evidence that two of the Complainant’s UAE entities were customers of the Respondent for several years beginning in 2009, without questioning the Respondent’s use of the name “Descon”. The Respondent argues that it has rights or legitimate interests in using the disputed Domain Name, as it has been using it for a bona fide business for more than thirty years, a business that it has been licensed to operate in UAE under a “Descon” name.

Held: The Panel finds that for some twenty years, before notice to the Respondent of the dispute in 2022, the Respondent used the disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of services. Moreover, the record includes email correspondence from 2013 between one of the Complainant’s UAE entities and the Respondent, using the disputed Domain Name, in connection with the business they conducted together at that time. Further, the Panel finds that the Respondent has been commonly known by a name closely corresponding to the disputed Domain Name for over thirty years, as the Respondent has been licensed under a “Descon” name in UAE since March 1994. These facts support a conclusion that the Respondent has rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name that accrued before the dispute arose.

This conclusion would be undermined if there were persuasive evidence that the Respondent selected its company names, under which it was licensed to do business in UAE in 1994 and has operated commercially since, to exploit the Complainant’s DESCON trademark. In that case, this could not be deemed a “legitimate” interest in the disputed Domain Name for Policy purposes. But the burden of proof here is on the Complainant, and the evidence is hardly conclusive. The Complainant did not have a domain name corresponding to “Descon” until September 1996, two years after the Respondent was established. The Complainant further asserts that the Parties are in the “same line of business”, but the Respondent argues otherwise. The Complainant had a subsidiary with a “Descon” name licensed in UAE since 1984, but the descriptions of pre-1994 UAE projects attached to the Complaint tend to support the Respondent’s assertion that the Parties do not perform the same services.

On some occasions, the Parties serve the same clients, but it is not clear that they compete for the same work as the Complainant suggests. There is evidence in the record that the Parties have done business with each other, but there is no evidence in the record of actual customer confusion, intentional or otherwise. The Panel finds on this record that the Complainant has not demonstrated that the Respondent, more likely than not, set up its business in 1994 under a name imitative of the Complainant’s mark, which was not then registered in UAE, to exploit the Complainant’s reputation. Therefore, the Respondent had a legitimate interest in subsequently registering a corresponding domain name, which it maintains to this day for the same business.

RDNH: The Complainant was well aware of the Respondent’s long-term business under the “Descon” name and the corresponding domain name. Indeed, the Complainant’s entities in UAE had done business with the Respondent over a period of several years, long after the Respondent registered and began using the disputed Domain Name, including corresponding with the Respondent by email using the disputed Domain Name. The Complainant did not mention these facts in the Complaint or more than cursorily addressed the obvious impediment to the second element of the Complaint.

The Complainant offered little to show that its mark, unregistered in UAE at the time, was nevertheless known to the Respondent and that the Respondent likely targeted the mark when the Respondent set up its company in the UAE in 1994. The Parties have done business together at times over the years since, and it was nearly 30 years before the Complainant decided to characterize the disputed Domain Name as an instance of cybersquatting. It appears more a case of RDNH, especially at this remove of time. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complaint has been brought in bad faith and constitutes an attempt at RDNH.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: United Trademark & Patent Services, United Arab Emirates (“UAE”)

Respondents’ Counsel: Gowling WLG (UK) LLP, UAE

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Bookmark this case for reference to an excellent discussion of “legitimate interest” in the context of identical marks. As the Panel observed, “the Respondent has been commonly known by a name closely corresponding to the disputed domain name for over thirty years, as the Respondent has been licensed under a “Descon” name in UAE since March 1994”. Interestingly however, the Panel also noted that “if there were persuasive evidence that the Respondent selected its company names…in order to exploit the Complainant’s DESCON trademark [then] in that case, this could not be deemed a “legitimate” interest” [emphasis added].

Domain Name Subject of Concurrent Court Proceedings

Kostel, LLC and Constantin Calugher v. mohamad atef, NAF Claim Number: FA2405002100428

<alternativepods .com>

Panelist: Mr. Charles A. Kuechenmeister, (Chair); Mr. Steven M. Levy; Mr. Douglas M. Isenberg

Multiple Complainants: Two parties filed this administrative proceeding as Complainants. The rules governing multiple complainants are Rule 3(a) and Forum’s Supplemental Rule 1(e). Previous panels have interpreted the Forum’s Supplemental Rule 1(e) to allow multiple parties to proceed as one party where they can show a sufficient link to each other. In this case, Complainant Constantin Calugher is the sole member of Complainant Kostel, LLC, as shown by the entity documents issued by the State of Illinois and the United States Treasury Internal Revenue Service. The Respondent confirms the accuracy of this evidence. This entity relationship demonstrates a sufficient nexus among the named Complainants to meet the requirements of Supplemental Rule 1(e). It is thus proper for both Complainants to file and prosecute a single Complaint.

Other Legal Proceedings: Two court cases involving these parties, the same business relationship they previously shared and the Domain Name, are currently pending. In both court actions, the parties assert conflicting claims, which are fact-sensitive, and fully at issue in the Illinois state court case. The Respondent argues that this Panel should dismiss the Complaint, allowing the judicial and USPTO proceedings to take their respective courses. The Complainant contests that argument. In addition to the two court cases, the Respondent has filed a cancellation proceeding with the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) seeking to cancel the Complainant’s USPTO registration of the ALTERNATIVE PODS mark.

In terms of Rule 18, the Panel thus has the discretion to terminate or continue with the UDRP administrative proceeding when outside litigation related to the domain name is pending. UDRP panels have often proceeded to a decision despite concurrent court proceedings when the domain name issues are ancillary to other issues in those proceedings and the domain name issues can be resolved without reference to the remedies at issue in the judicial proceedings. In this case, control of the domain name is central to the other remedies sought in the court cases, as it is the only means by which the parties’ customers can gain access to the parties’ retail outlets. More importantly, resolving the domain name issue in this case necessarily involves sorting through the same competing factual allegations that will determine the other issues in those cases.

The UDRP was intended to resolve cases of clearly abusive registrations. It was not intended to resolve complex factual disputes and by design provides none of the customary tools, such as discovery, rules of evidence, and evidentiary hearings with cross-examination, for performing that function. This case arises out of the dissolution of a previous business relationship. As such it is outside the scope of the UDRP, and resolving the factual issues involved in this matter is well beyond the limited means available for that purpose under the UDRP. The Panel will exercise its discretion in favor of terminating this proceeding.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Ilya R. Lapshin of IRL Legal Services, LLC, Massachusetts, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Neil Peluchette of Taft Stettinius & Hollister LLP, Indiana, USA

Comment by Newsletter Editor, Ankur Raheja: The 3-Member Panel’s decision to terminate these proceedings is in line with the intended scope of the UDRP, which is designed to address clear-cut cases of cybersquatting rather than complex factual disputes stemming from business dissolutions. Considering the ongoing judicial and USPTO proceedings that require detailed factual determinations essential for resolving the domain name dispute, the Panel appropriately exercised its discretion under Rule 18. This approach ensures that the more comprehensive judicial processes, equipped with discovery and evidentiary rules, are utilized to address the intricate matters at play. Also See: 891990 Ontario Inc., DBA Routes Car Rental v. Ashish Philip, CIIDRC Case Number 21833-UDRP, covered under vol. 3.46.