Snap! We got RDNH’d!

It is satisfying to see that the Panel critically reviewed the Complainant’s claim of common law rights. All too often Panels will give a Complainant an undeserved pass under this part of the three-part UDRP test, but here, the Panel declined to find common law rights based upon a close look at the provided evidence, which apparently consisted of recent documents and a business registration. The Panel properly noted that proof of a mere registration of a company with a corresponding name, without more, is not enough to demonstrate that common law rights have been established. Read commentary…

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 3.45), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Snap! We got RDNH’d! (snapmobile .com *with commentary)

‣ Panelist Catches a Whiff of Enterprising Respondent (enterprise .ir *with commentary)

‣ ‘Discrepancies’ Led to Independent Research by Panelist (wechat .ai *with commentary)

‣ When is a RedFig Just a Redfig? (redfig .com *with commentary)

‣ Nominative Fair Use or Impersonation in Furtherance of an Unlawful Act? (snapbreaker .com *with commentary)

—-

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

Snap! We got RDNH’d!

<snapmobile .com>

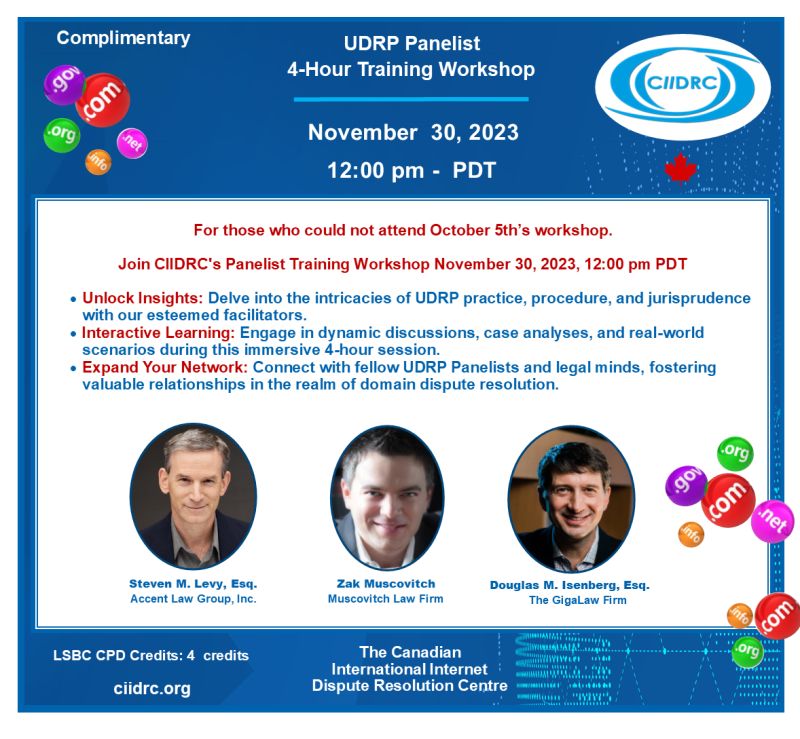

Panelist: Mr. Douglas M. Isenberg (Chair), Mr. Martin Schwimmer and Honorable Mr. Charles Kuechenmeister

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 2014, operates a “group-based digital fundraising platform… which has led to over 100,000 teams, clubs, and organizations across the United States raising over USD $700 million. The Complaint claims common law rights throughout the United States since at least as early as 2014 to its trademark SNAP! MOBILE. In support thereof, the Complainant provides a number of articles, business profiles, press releases and social media posts, and a certificate of liability insurance, all referring to “Snap! Mobile,” “Snap Mobile” or “Snap Mobile LLC.” The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is not using the disputed Domain Name to provide a bona fide offering of goods or services or a legitimate non-commercial or fair use” and instead has “attempt[ed] to sell the domain for nearly USD $400,000 since at least as early as 2018.” The Complainant further adds that bad faith exists pursuant to paragraph 4(b)(i) of the Policy and paragraph 4(b)(ii) of the Policy.

The Respondent, domain name investor, contends that it did not register or use the disputed Domain Name in bad faith because, inter alia, “I never knew about this company because they never even used a ‘snap mobile’ name anywhere, [w]hen I have a[c]quired [the disputed Domain Name]”; “[w]e are in the business of selling, developing and [m]anaging domain names” and “[i]t is well settled that a general offer to sell a domain name in and of itself does not constitute bad faith”; “offering it for sale as part of our stock in trade under the circumstances present in this case is entirely within our rights, regardless of Complainant’s claims to the Domain Name.” The Respondent further contends that the Complainant is a fundraising company operating in the USA, for only a specific class. It shows no evidence of the nature or extent of its operations, however, and shows no evidence of any presence in Canada.

Held: The Complainant states that it was founded in 2014, the documents that it provided do not show usage of the SNAP MOBILE trademark that might qualify as trademark usage until much more recently (those documents showing the use of the SNAP MOBILE name as Complainant’s corporate name are irrelevant here). Further, although the Complainant has provided some information about the scope and size of its business, it is unclear whether this business is associated with the alleged SNAP MOBILE name or with something else, such as what the Complainant has called “its first product — Snap! Raise.” Finally, although not required, the Complainant has provided no evidence of the degree of actual public recognition of the alleged SNAP MOBILE name or consumer surveys. Accordingly, the Panel has no basis on which to conclude that the Complainant has rights in the SNAP MOBILE name as a trademark.

As set forth in section 2.1 of WIPO Overview 3.0, this appears to be a case in which, “generally speaking, panels have accepted that aggregating and holding domain names (usually for resale) consisting of acronyms, dictionary words, or common phrases can be bona fide and is not per se illegitimate under the UDRP.” In this case, there is no evidence that the Respondent was (or should have been) aware of the Complainant and the alleged SNAP MOBILE trademark or that the Respondent registered or used the disputed Domain Name because of its possible value as a trademark. Indeed, the only use of the disputed Domain Name contained in the record is the Respondent’s attempt to sell it, which, as set forth above, can be bona fide under appropriate circumstances. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complainant has not established that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

Here, the Complainant has cited bad faith specifically under paragraphs 4(b)(i) and 4(b)(ii) of the Policy. With respect to paragraph 4(b)(i): The Complainant has provided as an annex a printout of a web page advertising the disputed Domain Name for sale for USD $399,888, an allegation that the Respondent does not appear to materially dispute. The question under this paragraph is whether the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name “primarily for the purpose of” selling it to the Complainant or to a competitor of the Complainant. Here, there is no such evidence, given that the Respondent has denied knowing of the Complainant or the alleged SNAP MOBILE trademark, a denial that seems plausible under the facts of this case, including especially because the Complainant has failed to establish trademark rights, as discussed above. Further, with respect to paragraph 4(b)(ii): Although the Respondent has admitted that it has registered many domain names, the Complainant has not alleged, nor is there any evidence in the record, that the Respondent has engaged in a “pattern of… conduct” targeting trademark owners, as the paragraph requires.

Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complainant has not established that the Respondent registered and is using the disputed Domain Name in bad faith.

RDNH: The reasons articulated by panels for finding RDNH as set forth in section 4.16 of WIPO Overview 3.0 and given the undertakings in paragraphs 3(b)(xiii) and (xiv) of the UDRP Rules, some panels have held that a represented complainant should be held to a higher standard. Herein the Complainant (which is represented by an attorney) still needs to establish even one of the three elements of the Policy. The Complainant (via its attorney) knew or should have known that it could not succeed in this proceeding – at least not based on the arguments and evidence submitted. As a result, the Panel finds that the complaint was brought in bad faith, in an attempt at RDNH.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Richard Alaniz of Lowe Graham Jones PLLC, Washington, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

It is satisfying to see that the Panel critically reviewed the Complainant’s claim of common law rights. All too often Panels will give a Complainant an undeserved pass under this part of the three-part UDRP test, but here, the Panel declined to find common law rights based upon a close look at the provided evidence, which apparently consisted of recent documents and a business registration. The Panel properly noted that proof of a mere registration of a company with a corresponding name, without more, is not enough to demonstrate that common law rights have been established. It is also interesting to see that the Panel undertook limited factual research to see if the Complainant had any pending US trademark registration, since after all, the Complainant had claimed use since 2014 and one would have thought that by now it would have at least applied for a registration, which it had not.

I also appreciate how the Panel found that the Complainant had not established an absence of Respondent rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name, since as the Panel noted that there was no evidence that the Respondent was or should have been aware of the Complainant’s alleged SNAP MOBILE common law trademark. This is the essence of a cybersquatting Complaint; not that the Complainant has a mark, but rather whether the Complainant’s mark was specifically targeted. Without evidence of a sufficient reputation at the material time of the Respondent’s Domain Name registration, there was simply no basis to find targeting and without targeting, there is no cybersquatting, generally speaking.

I also appreciate how the Panel referenced the correct and established principles supporting domain name investing under the Policy; a) “generally speaking, panels have accepted that aggregating and holding domain names (usually for resale) consisting of acronyms, dictionary words, or common phrases can be bona fide and is not per se illegitimate under the UDRP”; b) “as long as the domain names have been registered because of their attraction as dictionary words, and not because of their value as trademarks, this is a business model that is permitted under the Policy.”

This decision would have been a good decision even if the Panel’s analysis and conclusions ended there. But the Panel also fulfilled its additional duty of considering RDNH. The Panel concluded that since the Complainant, who was “represented by an attorney, failed to established even one of the three elements under the Policy”, the Complainant via its attorney knew or should have known that it could not succeed in this proceeding – at least not based on the arguments and evidence submitted”, and accordingly declared that the Complainant was brought in bad faith.

Panelist Catches a Whiff of Enterprising Respondent

Enterprise Holdings, Inc. v. Izak Sedighpour, WIPO Case No. DIR2023-0009

<enterprise .ir>

Panelist: Mr. Assen Alexiev

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a privately owned American car rental company founded in 1957. It operates several car rental brands, including Enterprise Rent-A-Car, National Car Rental, and Alamo Rent-A-Car. Together with its affiliated companies, the Complainant operates in more than 100 countries through over 8,000 offices and employs about 80,000 persons. The Complainant is the owner of a number of trademark registrations for the sign ENTERPRISE, including the Iranian trademark ENTERPRISE (registered on April 28, 2001). The Complainant is also the owner of the domain name <enterprise .com>, which resolves to its principal e-commerce website for online vehicle rental. The disputed Domain Name was registered on July 19, 2010, and resolves to a parking webpage in Persian, which invites visitors to send a price offer to the owner of the disputed Domain Name if they want to buy it.

The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Name misappropriates sufficient textual components from the Complainant’s name, so that an ordinary Internet user who is familiar with this name would, upon seeing the disputed Domain Name, think that an affiliation exists between it and the Complainant. The Complainant further notes that on April 10, 2023, it sent a cease-and-desist letter to the Respondent, asking him to transfer the disputed Domain Name to the Complainant, to which the Respondent did not reply. The Respondent did not reply to the Complainant’s contentions during these proceedings as well.

Held: The Respondent has chosen not to submit a Response, and there is no evidence that it has responded to the Complainant’s cease-and-desist letter either. The Respondent has neither referred to the dictionary meaning of the word “enterprise”, nor shown or even alleged that he has genuinely used or has intended to use the disputed Domain Name in connection with its dictionary meaning, and not to trade off third-party trademark rights. The disputed Domain Name is not actively used but resolves to a parking webpage containing an invitation to interested parties to submit offers for purchase of the disputed Domain Name. Considering the above, and in the absence of any argument or explanation from the Respondent, the Panel finds no basis for a conclusion that the Respondent has rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name solely by virtue of the fact that “enterprise” is a dictionary word, and not only a trademark of the Complainant.

Having reviewed the record, the Panel finds the absence of active use of the disputed Domain Name does not prevent a finding of bad faith in the circumstances of this proceeding. WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.3. The Panel notes the reputation of the Complainant’s ENTERPRISE trademark, the fact that the disputed Domain Name is identical to it, the absence of active use of the disputed Domain Name and the notice that it is for sale, coupled with the failure of the Respondent to submit a response, to provide any evidence of actual or contemplated good-faith use of the disputed Domain Name or to refer to any plausible good faith use to which the disputed Domain Name may be put. Therefore, the Panel finds that in the circumstances of this case, the passive holding of the disputed Domain Name does not prevent a finding of bad faith under the irDRP. Based on the available record, the Panel therefore finds the third element of the irDRP has been established.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Saba & Co. Intellectual Property s.a.l. (Offshore) Head Office, Lebanon

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Guest Case Comment by ICA Director, Nat Cohen:

Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

The Complainant Enterprise Holdings is a global company and by far the most dominant user of the dictionary word “Enterprise” as a brand. It owns an extensive portfolio of Enterprise domain names, including domain names comprised of the word “Enterprise” and the country code TLD (ccTLD) of most of the major countries in the world. According to the Enterprise-Car-Rental web site, it operates in nearly 100 countries around the world – but Iran is not one of them. Due to an extensive sanctions regime imposed by the United States on Iran dating back to shortly after the Iranian revolution in 1979, it has long been impermissible for companies with a nexus in the United States to conduct business in Iran. Enterprise Holdings has no locations in Iran.

Nor does Enterprise Holdings own the ccTLD for “enterprise” in every country in which it conducts business. Enterprise Holdings is apparently not the registered owner of enterprise .jp (Japan), enterprise .com .au (Australia), enterprise .ru (Russia), enterprise .ng (Nigeria), enterprise .bg (Bulgaria) and enterprise .it (Italy), among others.

The Panel in Enterprise .ir recognized that since “enterprise” is a dictionary-word it is not exclusively associated with any one company. The Panel looked for guidance to the relevant section, 2.10.1, of the WIPO Overview. Section 2.10.1 reads in relevant part as follows:

2.10.1 Panels have recognized that merely registering a domain name comprised of a dictionary word or phrase does not by itself automatically confer rights or legitimate interests on the respondent; panels have held that mere arguments that a domain name corresponds to a dictionary term/phrase will not necessarily suffice. In order to find rights or legitimate interests in a domain name based on its dictionary meaning, the domain name should be genuinely used, or at least demonstrably intended for such use, in connection with the relied-upon dictionary meaning and not to trade off third-party trademark rights.

Guided by the WIPO Overview, the Panel found that the Respondent had no legitimate interest in enterprise .ir:

The Respondent has neither referred to the dictionary meaning of the word “enterprise”, nor shown or even alleged that he has genuinely used or has intended to use the disputed domain name in connection with its dictionary meaning, and not to trade off third-party trademark rights. The disputed domain name is not actively used, but resolves to a parking webpage containing an invitation to interested parties to submit offers for purchase of the disputed domain name.

Yet WIPO Overview’s coverage of this issue is incomplete. According to its guidance, a domain name registrant has a legitimate interest in a dictionary word domain name used in its dictionary sense, but not in a dictionary word domain name used to trade off third-party rights. But what of domain name investors? If a domain name investor owned desk .com and merely offered the domain name for sale, the domain name investor is neither using the domain name in its dictionary sense to sell desks, nor is the domain name being used to trade off third-party rights. The desk .com domain name has inherent value. The word “desk” has independent meaning rooted in a widely shared language and belongs to no one entity such that no entity can claim a monopoly on all commercial use of a dictionary word. Does not a domain name investor have a legitimate interest in owning desk .com as a business asset in order to conduct his legitimate business of dealing in inherently appealing domain names? Why is the WIPO Overview unwilling to acknowledge the legitimate interest of domain name investors in dealing in domain names that have inherent value outside of any third-party rights?

It raises questions about the agenda underlying the WIPO Overview that it fails, even in the third edition published at the late date of 2017, to acknowledge that domain name investors could have a legitimate interest in a dictionary word domain name, such as desk .com, despite not operating a business selling desks at the domain name.

Zak Muscovitch offered a close examination of this issue in his comment on the sage.ai decision in Digest issue 3.37, which is well worth reading in full. In particular, he cites Panelist Willoughby who addresses this deficit in the WIPO Overview by recognizing that a Respondent may have a legitimate interest in a dictionary-word domain name even if it is not used in its dictionary sense:

Panelist Willoughby expressly states that he does not accept the argument that “because the Respondent is not using the disputed domain name for a use based on the dictionary meaning of “sage”, the Respondent cannot have a legitimate interest in respect of it” and believes that this argument is misconceived. I could not agree more.

In analyzing the bad faith element, the Panel invokes the doctrine of passive holding and correctly notes that a key aspect of the doctrine is whether the domain name could plausibly be put to a good faith use. According to the doctrine of passive holding, if the disputed domain name could plausibly be put to a good faith use, a finding of bad faith use cannot be justified.

Yet since the non-responding Respondent failed to appear to make the argument that there could plausibly be a good faith for <enterprise .ir>, the Panel finds that the passively held <enterprise .ir> domain name is being used in bad faith. The Panel in effect makes the counterfactual finding that there is no plausible good faith use to which the enterprise .ir domain name could be put.

Why did the Respondent not respond? We do not know. We do know that the Respondent is identified as a resident of Iran, that the registrar IRNIC is based in Iran, and that the domain name resolved “to a parking webpage in Persian”. This would suggest that according to UDRP Rule 11, and as a matter of basic fairness to the Respondent, that the Complaint be provided to the Respondent in Persian so that the Respondent could understand the allegations against him. The decision does not address the question of the language of the proceedings.

The Panel likely sensed that something was amiss with the registration, and in the absence of a response, viewed a decision to transfer the domain name as a just outcome. Indeed, the same Respondent in the <enterprise .ir> dispute, Izak Sedighpour, has a history of being found guilty of cybersquatting for registering .ir domain names corresponding to the well-known brands of poclain .ir, merz .ir, and alfalaval .ir. As no mention is made of Sedighpour’s prior history in the decision, it appears likely that this was not submitted into evidence by the Complainant, nor that the Panel uncovered it through independent research.

Here the experienced Panel had an accurate sense of smell in recognizing that something was off. Yet to reach an outcome that is apparently justified considering this additional information, the Panel had to reach a conclusion that was not justified by applying the Policy to the evidence in the record.

It is decisions such as this that led me to write a CircleID article entitled “Smells like Cybersquatting? How the UDRP “Smell Test” Can Go Awry. The article starts off:

The UDRP has the form of a substantive Policy, but it operates as a “smell test”.1 If the evidence smells bad, the panel will likely order a transfer. If it doesn’t, the panel won’t.

If the UDRP only amounts to a smell test, ownership rights of domain names become subject to unreliable decision-making.

‘Discrepancies’ Led to Independent Research by Panelist

Tencent Holdings Limited v. Ravi Shrestha, WIPO Case No. DAI2023-0021

<wechat .ai>

Panelist: Mr. Warwick A. Rothnie

Brief Facts: The Complainant has operated the “WeChat” instant messaging, social media, and mobile payment application since 2011. By 2018, it had over 1 billion active users around the world. The Complaint owns at least three registered trademarks for WECHAT including EU Trademark (March 21, 2012); US Trademark (December 3, 2013); and China Trademark (March 7, 2015). According to the Whois record, the disputed Domain Name was registered on December 16, 2017, while the Respondent contends that he registered it in March 2016, “to ideate upon my exploratory curiosity” and that the Respondent’s idea has morphed over time and he is now working on creating a crowdsourced conversational AI bot. The Respondent further contends that the Complainant was not involved in AI initiatives in 2016 and that “we chat” is a common expression in English like “we sign” or “we talk” and claims he never thought about the Complainant or its “ancillary” products when registering the disputed Domain Name.

According to the Complaint, the disputed Domain Name does not resolve to an active website. However, at the time of this decision, it resolves to a website which appears to host a number of “posts” on an eclectic range of subjects. A notable feature of the landing page is that the first five posts are dated in 2019, there are then other posts dated in 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, and with the first post being dated September 19, 2010. In order to examine these discrepancies, the Panel consulted the Wayback Machine. It shows that a website at the disputed Domain Name has been crawled six times between May 25, 2017 and March 19, 2023. The Panel was unable to retrieve the pages archived on the two dates in 2017. The pages archived on March 14, 2018, and May 4, 2019, appear to be provided by the Registrar or host and are headed “Future home of […] wechat .ai”. The pages on December 26, 2021, and March 19, 2023, redirect to the Dan .com page headed “The name wechat .ai is for sale”.

Held: The Respondent does not include evidence such as business plans, correspondence related to business formation, or the like which might corroborate its various claims. If as the Respondent says the idea of creating a crowdsourced conversational AI bot was something that morphed and developed over time, it is difficult to accept that idea explains his choice of the disputed Domain Name when he registered it and it is also inconsistent with the Wayback Machine evidence. In these circumstances, it is not open to the Panel to accept the Respondent’s purported explanation for the adoption and proposed use of the disputed Domain Name. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complainant has established the required prima facie case under the Policy that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

Generally speaking, a finding that a domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith requires an inference to be drawn that the respondent in question has registered and is using the disputed Domain Name to take advantage of its significance as a trademark-owned by (usually) the complainant. Even in 2016 and 2017, it seems very likely that “WeChat” was very well and widely known around the world, not just in China. In light of that, the Panel considers it much more likely that the Respondent was well aware of the Complainant and its trademark when registering the disputed Domain Name and did so to take advantage of its resemblance to the Complainant’s trademark. In those circumstances, therefore, the Panel finds that the disputed Domain Name was registered in bad faith contrary to the Policy.

The failure of the Respondent’s crowdsourced conversational AI bot claim and the offering of the disputed Domain Name for sale through Dan .com indicates that the current website form is merely colourable or pretextual. Moreover, the disputed Domain Name offered for sale involves opportunistic speculation on the value of the disputed Domain Name arising from its resemblance to the Complainant’s trademark. Accordingly, the Panel finds the Respondent has registered and used it in bad faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Kolster Oy Ab, Finland

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-reprsented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

The Panelist correctly seized upon the Respondent’s selection of “WeChat” for a domain name. Today, WECHAT is an extraordinarily well-known app particularly in China, but also elsewhere with 1 billion users. Surely, if the Domain Name had been registered today, there would be little doubt that the Respondent hadn’t coincidently registered it, but rather had done so with full awareness of the Complainant and his professed intended use of the Domain Name was a thinly veiled ruse. But the Domain Name was not registered recently. Rather, it was registered in 2016 or 2017 by the Respondent and the Panel therefore concluded that even at that time, it “seems very likely that “WeChat” was very well and widely known around the world, not just in China”. This does seem like a solid assumption given that the Complainant’s evidence was that by 2018, the Complainant had over 1 billion active users around the world. Nevertheless, this is a helpful lesson for complainants; it is important to prove registration at the material time, i.e. prior to the date of registration, rather than currently.

I do however want to take a moment to address the Panel’s use of archive .org to “examine [certain] discrepancies”, namely how it could be that the Respondent had web content purporting to be dated from as early as 2010, when the Respondent had only registered the Domain Name in 2016 or 2017. As noted by the Panel, “according to the Complaint, the disputed domain name has not resolved to an active website. The Complaint, however, did not include a screenshot to verify this”, which is unfortunate as a Complainant should have included evidence of this. That being said, the Complainant’s failure led the Panel quite properly reviewing the website himself to ensure that the Complainant’s allegation was correct.

Although it is generally a best practice to rely solely on the pleadings where possible, particularly in defended cases, it is well-established that a Panelist may conduct limited independent research of publicly available sources. An associated website would be the most obvious and most appropriate such source even if the Complainant had provided a screenshot, if only to see for oneself how the Domain Name was currently being used. The current use of a Domain Name is something that both a Complainant and a Respondent would have equal access to and could be addressed by a Complainant (even via a supplemental filing if the Domain Name’s use had changed subsequent to the original filing) and by a Respondent who of course would have access to its own publicly available website.

When visiting the website “at the time this decision is being prepared”, the Panel noted that the disputed domain name “resolves to a website which appears to host a number of posts” on an eclectic range of subjects” and that “a notable feature of the landing page is that the first five posts are dated in 2019, there are then four posts dated in 2018, four posts dated in 2017, three posts in 2015, 14 in 2014, 10 in 2013, and with the first post being dated September 19, 2010.” The fact that posts existed from a time frame prior to the Respondent’s own claimed registration date of 2016, constituted a “discrepancy” and the Panel noted that the Respondent “does not address this issue”. This issue however was not put into the record by the Complainant who did not submit a screenshot but had claimed that the Domain Name had not been used. On the other hand, the Respondent of course could have explained this issue had it been pointed out by the Complainant, or even by the Panel in a Procedural Order. There could have been an explanation for this discrepancy but the Respondent was not provided any opportunity to address it and was apparently expected to address it even though he was never put on notice of it.

The Panel then consulted archive .org to “examine these discrepancies”. He found that all available archived pages were either registrar ‘coming soon’ type pages or directed to a ‘for sale’’ page on domain name marketplace, Dan .com. In other words, there was no history of archived pages showing the website featuring posts, including from as far back as 2010, leading to the conclusion that the website had been erected since the filing of the Complaint and had even misrepresented the dates of the posts. The Panel accordingly concluded that “in these circumstances, it is not open to the Panel to accept the Respondent’s purported explanation for the adoption and proposed use of the disputed domain name”. The Panel appears to be correct and reached a reasonable and very likely conclusion. Nevertheless, should not this issue have been put to the Respondent for a possible exculpatory explanation, no matter how unlikely? Procedural fairness would tend to require that a Respondent be put on notice of all evidence upon which a Panel intends to rule and that a Respondent be given an opportunity to explain or refute evidence that a Panel himself found and which was not even relied upon by the Complainant, as was the case here. This is not to challenge the conclusion reached by the Panel but rather to draw attention to ensuring that the UDRP procedure, despite its expedited nature, should still attempt to afford both parties procedural fairness wherever reasonable possible. Here, if the Panel did not believe that the Complainant’s own case was sufficient, he should have dismissed or, having conducted his own research to uncover his own evidence, put such evidence to the Respondent if the Panel intended to rely upon it. In this case, the case could have probably been decided in favour of the Complainant without this additional Panelist-discovered research and in doing do, the Panel could have avoided this procedural fairness issue altogether.

When is a RedFig Just a Redfig?

Redfig LLC v. Bill Patterson / Reserved Media LLC, NAF Claim Number: FA2310002065116

<redfig .com>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith (Chair) and Mr. Steven M. Levy and Professor Mr. David E. Sorkin

Brief Facts: The Complainant uses the REDFIG mark to provide services relating to computer programming and software. The Complainant owns rights to a trademark consisting of the word “redfig” and a fig device mark through its registration with the USPTO (registered on March 24, 2020; first use: August 1, 2019). The Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name in auction, after its previous registration expired, on September 21, 2019. The Respondent contends that the Respondent’s registration of the Domain Name predates the Complainant’s registration of the REDFIG mark and at the time of acquisition, the Respondent was unaware of the Complainant and its use of or reputation in the REDFIG mark, which likely was minuscule at the date of registration.

The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Name is listed for sale on a third-party site for a sum which is well in excess of the cost of purchasing a domain name from a registrar. The Respondent further contends that the disputed Domain Name consists of a non-distinctive and non-exclusive two-word term and that the Respondent has registered various domain names consisting of two-word descriptive terms including <redbird .com>, <redsky .com>, and <blueapple .com>. The Complainant has not satisfied its burden of showing that the disputed Domain Name was registered and used in bad faith by the Respondent. Rather the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name following its expiry entirely for its descriptive properties.

Held: The Panel finds that the Complainant has failed to meet its burden of proof of bad faith registration and use under the Policy, as the Complainant provides no documentary evidence of any use of or reputation in the REDFIG mark at the time, the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name. Even if the Complainant’s stated date of first use of August 1, 2019, is accurate, the Complainant would only have used the mark for a matter of weeks prior to the September 21, 2019 date the disputed Domain Name was acquired by the Respondent. The Respondent provides information and a clear explanation about when it acquired the disputed Domain Name and the reason it acquired the Domain Name, i.e., based on it becoming available after a recent expiration. It also provides evidence supporting the claimed good faith reason, namely that the disputed Domain Name is completely consistent with the other descriptive domain names held by the Respondent.

The Complainant has thus failed to satisfy its burden to demonstrate, on a preponderance of the evidence, that the disputed Domain Name was registered in bad faith by the Respondent; i.e. registered with awareness of the Complainant and mal-intent instead of being registered because it consisted of a two-word descriptive term. As the Complainant cannot prove registration in bad faith as per Policy, the Respondent’s use of the disputed Domain Name is immaterial, as the Policy requires a showing of bad faith registration and use. Moreover, the fact that the Respondent is seeking to sell the Domain Name does not change the fact that the Complainant has failed to establish that the Domain Name was registered in bad faith, a requirement of the Policy. Therefore, the Panel finds the Respondent did not register the disputed Domain Name in bad faith.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Represented Internally

Respondents’ Counsel: John Berryhill, Pennsylvania, USA

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: This case presents a “classic” set of circumstances:

- The Complainant’s trademark corresponds to a descriptive term;

- The Complainant’s trademark registration post-dates the Respondent’s domain name registration;

- The Complainant provided no evidence of reputation from prior to its trademark registration that would suggest targeting; and

- The domain name was listed for sale for more than its registration fee.

To the Complainant, this all apparently added up to a case worthy of bringing a UDRP. This kind of ‘case’ is brought with some regularity and puts the domain name registrant to considerable effort, expense, and risk, even if by and large such cases are easily batted down by UDRP Panels as was done here. It should be pointed out however, that although such cases are brought with some regularity, they do not represent a substantial percentage of UDRP cases brought overall, the vast majority of which are ‘no brainer’ cybersquats that the UDRP was intended to efficiently address. That being said, registrants must but up with this at their own cost as the unintended ‘collateral damage’ of the UDRP system. That is indeed unfair, though trademark owners also must bear constant cybersquats targeting their trademarks and are thereby forced to employ the UDRP at considerable cost and effort as well. In that sense, both trademark owners and bona fide registrants pay an unfair price when it comes to the UDRP.

Is there a solution to this problem? There could be. Meritless complaints could be better avoided with improved information and education directly tied to the Complaint-filing process so that the futility of some cases is front and center for prospective complainants prior to filing. RDNH also plays a role in exacting an admittedly mostly symbolic price on abusive complainants but can also potentially serve as a deterrent to complainants who would otherwise be able to abuse the Policy without any consequence. Yet more still must be done to assist bona fide registrants in avoiding the necessity of battling meritless complaints brought by simply covetous complainants.

To address the frustration of trademark owners who must constantly expend time and money in a seemingly never-ending battle against incessant cybersquatting, a fast-track for repeat complainants should be considered. There is no reason why a famous and highly distinctive brand like WELLS FARGO for example, should have to pay USD $1,500 to $,2000 and wait a month or more to obtain the transfer of a cybersquatted domain name. Look at the volume of UDRP cases that Wells Fargo has had to bring (132). An expedited and more cost effective procedure for complainants who bring repeated UDRPs in respect of the same trademark over and over again, should be seriously considered.

Nominative Fair Use or Impersonation in Furtherance of an Unlawful Act?

Snap Inc. v. jeronie sila, NAF Claim Number: FA2310002065981

<snapbreaker .com>

Panelist: Ms. Dawn Osborne

Brief Facts: The Complainant owns the SNAPCHAT and SNAP trade marks used since 2011 and a trade mark for its ghost logo for computer-related services all registered in, inter alia, the USA. The disputed Domain Name registered in 2015 has been used for a site offering competing software services purporting to allow access to Snapchat accounts featuring the Complainant’s SNAP and SNAPCHAT trademarks and very similar ghost graphic with a similar colour yellow to that used by the Complainant.

The Complainant alleges that using a trade mark to drive traffic to a competing website and gathering Internet user details for phishing purposes is not a bona fide offering of goods or services or a legitimate non-commercial fair use. The use on the Respondent’s website of the Complainant’s SNAP and SNAPCHAT marks and similar ghost logo with a similar yellow to that used by the Complainant shows that the Respondent is aware of the Complainant and its business. The Respondent failed to submit a Response in this proceeding. However, the Respondent had already removed the ghost graphic after being contacted by the Complainant.

Held: The website attached to the disputed Domain Name uses the Complainant’s SNAP and SNAPCHAT word marks and ghost logo and a similar yellow colour to that of the Complainant for a competing site purporting to offer access to Snapchat accounts. It does not make it clear that there is no commercial connection with the Complainant. The Panel finds this use confusing. The site further appears to be gathering information for phishing purposes. This cannot be considered a bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate noncommercial or fair use. The Respondent has not answered the Complaint or rebutted the prima facie case evidenced by the Complainant as set out herein. As such the Panelist finds that the Respondent does not have rights or a legitimate interest in the disputed Domain Name.

In the opinion of the panelist, the use made of the Domain Name in relation to the Respondent’s site is confusing and disruptive in that visitors to the site might reasonably believe it is connected to or approved by the Complainant. The use of the Complainant’s word marks, ghost logo and yellow trade dress and the reference to the Complainant’s services on the Respondent’s website shows that the Respondent is aware of the Complainant and has intentionally attempted to attract for commercial gain Internet users to its website by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s trademarks. The Respondent further uses the disputed Domain Name to engage in apparent phishing. As such, the Panelist believes that the Complainant has made out its case that the Domain Name was registered and used in bad faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Emily A. DeBow of Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP, California, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: This case raises the issue of when does use of a Complainant’s mark constitute nominative fair? And when does it constitute unauthorized use for impersonation? Here, the issue is somewhat muddled because of the nature of the purported service being offered by the Respondent, which if not unlawful, certainly doesn’t appear “bona fide”.