Three-Letter .COM Registered in 1993, But No RDNH

DNW .COM wrote about this case in its article. “GSF.com cybersquatting dispute should have been reverse domain name hijacking”. I understand the frustration expressed by DNW.com in criticizing the absence of an RDNH finding; “But despite this innocent domain owner having to hire a lawyer to defend against a baseless case, and despite that domain owner asking for a finding of reverse domain name hijacking, and despite the Complainant being represented by counsel, the panelist denied a finding of reverse domain name hijacking”. I also understand DNW.com’s criticism of the panelist’s brief explanation for not finding RDNH: “Based on the available record, the Panel sees insufficient basis on balance to conclude that the Complaint was brought in bad faith and accordingly declines to make a finding here of reverse domain name hijacking”. Read commentary.

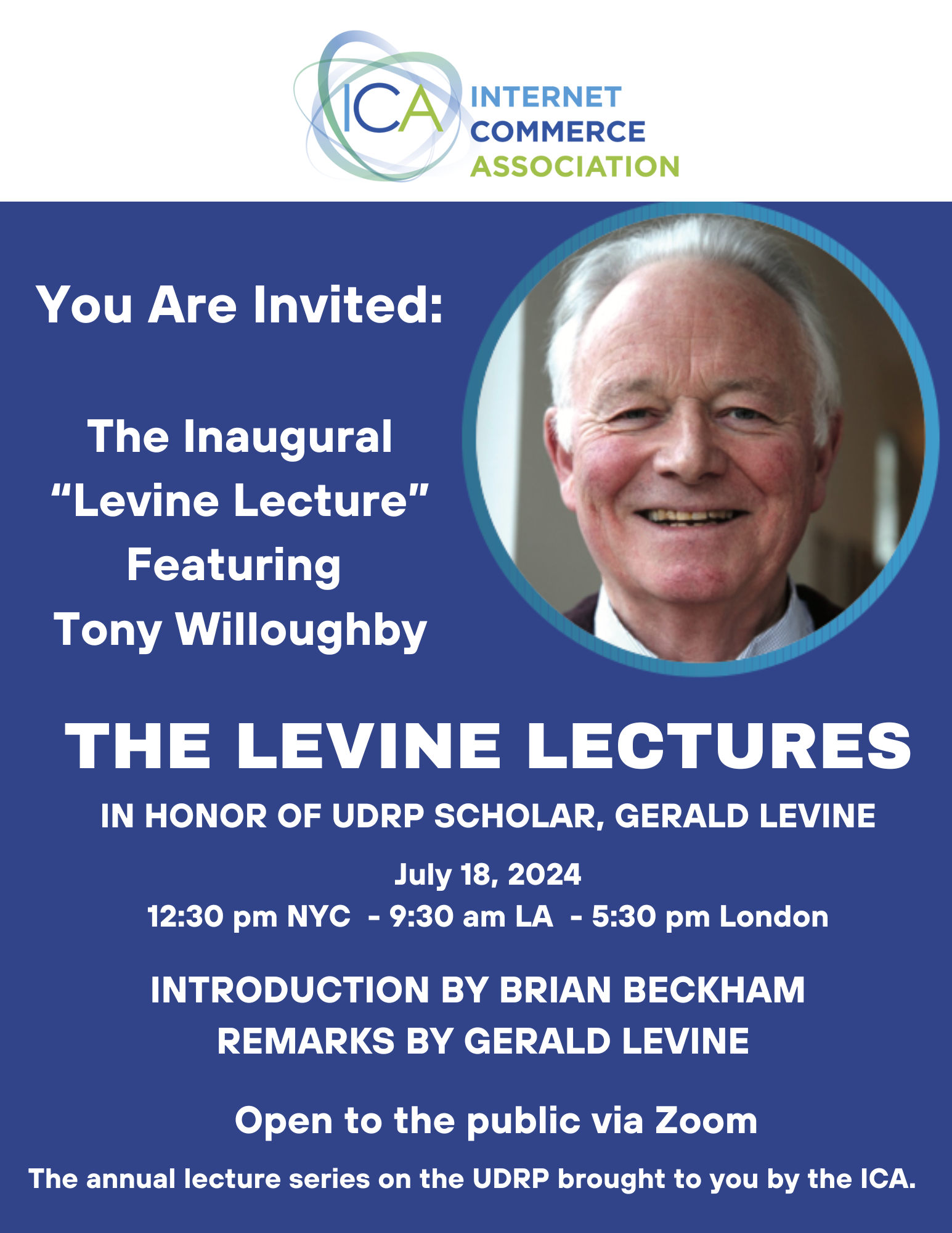

SIGN UP FOR THE INAUGURAL “LEVINE LECTURE” HERE

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.25), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Three-Letter .COM Registered in 1993, But No RDNH (gsf .com *with commentary)

‣ A Recital of Law on Domain Name Investing (proibs .com *with commentary)

‣ Why Was the Respondent’s Website Considered to be “Passive Holding”? (icessna .com *with commentary)

‣ Cybersquatting or a Genuine Business Dispute? (tommystatefarm .com) *with commentary)

‣ Appropriately Deferring to the Courts (claimshield .com) *with commentary)

Three-Letter .COM Registered in 1993, But No RDNH

Golden State Foods Corp v. Greg Foltz / GSF Consulting, NAF Claim Number: FA2404002095736

<gsf .com>

Panelist: Mr. Sozos-Christos Theodoulou

Brief Facts: The Complainant asserts rights in the GSF mark based upon a registered trademark with the USPTO (applied for on June 27, 1989 and registered on March 31, 1992). In addition, the Complainant refers to three other US trademark registrations, two for GOLDEN STATE FOODS / one for GOLDEN STATE FOODS CORP. The Complainant essentially contends, in the sense of paragraph 4(a) of the Policy, that the disputed Domain Name is confusingly similar to its GSF and/or GOLDEN STATE FOODS/GOLDEN STATE FOODS CORP trademarks. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has not demonstrated any use of the disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods and services or a legitimate non-commercial or fair use of the disputed Domain Name; and that, the disputed Domain Name has been registered and is being used in bad faith, as an inactive website.

The disputed Domain Name was registered on August 11, 1993 by the Respondent. The Respondent contends that the Complainant, despite the disputed Domain Name being identical to the Complainant’s trademark GSF, has no trademark rights on the disputed Domain Name, as the Respondent is not a competitor of the Complainant in the same field of business. The Respondent further contends that the Respondent has rights and legitimate interests to the disputed Domain Name since its registration back in 1993, and that he registered and used the disputed Domain Name in good faith, for his own business and/or family. The Respondent also claims that the Complainant has shown behavior consistent with reverse domain name hijacking.

Held: In view of the foregoing, the Panel is satisfied that the Complainant has established a prima facie case that the Respondent lacks rights and legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name. In order to rebut Complainant’s arguments, the Respondent had the possibility to make its own defence. Hence, the Respondent argued on the basis of his registration of the disputed Domain Name back in 1993, and presented evidence of legitimate use of the disputed Domain Name in more than 30 years, for both his own business and his family. He may not have used it for a website, but the use did include email addresses for him and for his family members.

This time, the Respondent’s argument that, there is no direct competition between him / his business and the Complainant meets the Panel’s agreement, as it confirms the legitimate character of the disputed Domain Name’s use, without any proven intent to mislead consumers towards the Respondent’s business by taking advantage of any likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s business. Although it could be interesting to look into the theory of latches, the Panel finds it unnecessary to refer here to the theory. In view of all the above, the Panel concludes that the Complainant has not satisfied Policy ¶ 4(a)(ii), because the Respondent has proven rights and/or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Rosaleen Chou of Knobbe Martens Olson & Bear LLP, California, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Christopher Newberg of KUIPER KRAEMER PC, Michigan, USA

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: DNW .COM wrote about this case in its article. “GSF.com cybersquatting dispute should have been reverse domain name hijacking”. I understand the frustration expressed by DNW.com in criticizing the absence of an RDNH finding; “But despite this innocent domain owner having to hire a lawyer to defend against a baseless case, and despite that domain owner asking for a finding of reverse domain name hijacking, and despite the Complainant being represented by counsel, the panelist denied a finding of reverse domain name hijacking”. I also understand DNW.com’s criticism of the panelist’s brief explanation for not finding RDNH: “Based on the available record, the Panel sees insufficient basis on balance to conclude that the Complaint was brought in bad faith and accordingly declines to make a finding here of reverse domain name hijacking”.

Nevertheless, I take a somewhat different view of the decision and the result. I firstly appreciate that the Panel even dealt with the claim of RDNH as sometimes Panels shirk their duty to even consider RDNH despite the requirement under the Rules that RDNH be considered where appropriate (Rule 15e: “If after considering the submissions the Panel finds that the complaint was brought in bad faith, for example in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking or was brought primarily to harass the domain-name holder, the Panel shall declare in its decision that the complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding” [emphasis added]). Here however, the Panel did in fact consider RDNH as it should have but determined that it was not called for in this case. Sometimes the existence of RDNH is so apparent and egregious that a Panel’s failure to find RDNH is simply unacceptable. But in other cases, such as here, there is at least a credible basis for denying RDNH.

Yes, the case was doomed to fail, but was this apparent only after the Response was filed or was it apparent to the Complainant before the Response was filed? Here, arguably the Complainant did not have the factual basis to realize that its case was doomed to failure because the Domain Name was not outwardly used by the Respondent and it was at least conceivable that it had been registered by the Respondent to target the Complainant. But there was no evidence of targeting whatsoever – over the course of a 30 year registration. And given the ubiquity of three-letter acronyms, on what reasonable basis could the Complainant have believed that it, from the entire universe of potential uses and meanings of the term, was the actual target of the registration? And what explanation did the Complainant have for waiting thirty years to bring the UDRP? Does that not suggest severe weakness and a lack of merit in its Complaint? These questions indeed point to possibility of RDNH. If the Panel reasonably decided that despite these points, “on balance” there was “insufficient basis” to conclude that the Complaint was brought in bad faith, then I believe it owed the Respondent a better and fuller explanation of ‘why’.

It is important to remember that legal decisions are primarily written for the unsuccessful party. Here, care was taken to explain to the unsuccessful Complainant why it did not succeed, but equal care should have been taken to explain to the Respondent why it was unsuccessful in not obtaining a declaration of RDNH. Moreover, if the Panel had undertaken a more robust and express analysis of the reasons for denying RDNH, then the process may have conceivably compelled the Panel to ultimately determine that RDNH was in fact warranted.

At the heart of the issue here, in my opinion, not the ultimate outcome of whether RDNH existed or not per se, but rather, short changing the Respondent from an appropriately detailed and reasoned basis for denying the Respondent’s “counter-claim”. A claim for RDNH deserves as much attention and consideration as a claim for bad faith registration and use. It is difficult to conceive of a Panelist denying a Complaint with such brevity as was employed in denying the Respondent’s claim for RDNH – even if on balance, RDNH was not appropriate as the Panel determined.

A Recital of Law on Domain Name Investing

Calmino group AB v. Domain Administrator, DomainMarket .com, WIPO Case No. D2024-1579

<proibs .com>

Panelist: Mr. John Swinson

Brief Facts: The Swedish Complainant is a healthcare company with focus on gut health. According to the Complainant’s website, it “was founded in 2003 and in 2010 we launched a product for the dietary management of IBS under the brand PROIBS”. IBS is an acronym for “irritable bowel syndrome” which is a common functional bowel disorder affecting the large intestine. The Complainant owns a portfolio of trademark registrations for PROIBS including Swedish Registration (May 15, 2009), and United States Registration (July 22, 2014). The Complainant markets its PROIBS product on its websites located at <proibs .eu> and <proibs .se>. The disputed Domain Name was registered by the Respondent on April 3, 2011, by the Respondent, who is in the business of creating, buying, and selling domain names. The Respondent offers domain names for sale through a secondary marketplace at <domainmarket .com> and lists its Domain Names for sale with third party sales channels, including Afternic and GoDaddy. At the time the Complainant was filed, the website at the disputed Domain Name listed the disputed Domain Name for sale at a proposed price of USD $194,888.

The Complainant alleges that the only possible intent for registering the disputed Domain Name is for the Respondent to make commercial gain misleadingly to divert consumers or to tarnish the trademark or service mark at issue. According to the Respondent, a representative of the Complainant contacted the Respondent and made inquiries about purchasing the disputed Domain Name in September 2011. Supposedly, the price at that time was USD $8,000. No sale took place. The Respondent owns approximately 50 domain names that start with “pro”, such as <proall .com>, <protelco .com>, <prosewer .com>, and <probeds .com>. The Respondent contends that “IBS” is a common acronym for “irritable bowel syndrome”, and provided examples of health products (apparently not associated with the Complainant) called or advertised using the terms PRO IBS and that it registered the disputed Domain Name in connection with its legitimate business of reselling premium domain names, which is a bona fide offering of goods and services that has an accepted place in the domain name industry.

Held: Dealing in domain names in the secondary market is a legitimate trading activity. By its very nature, it is speculative. A domainer usually has the intention of reselling domain names at a price in excess of the purchase price. Some domain names sell, and some sit on the shelf unsold; in either event, trying to make a profit by reselling domain names is not bad faith per se. The Complainant has not shown that the Respondent registered or used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith given that the disputed Domain Name was selected because of its potential association with irritable bowel syndrome, or potentially other “IBS” related terms. Moreover, the Respondent is in the United States and the Complainant is in Sweden. It is plausible that the Respondent was not aware of the Complainant’s 2009 trademark registration at the time that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in 2011. It is unclear when the Complainant first used its trademark, and there is no evidence before the Panel as to use or reputation of the PROIBS trademark in 2011 when the disputed Domain Name was registered. In addition, the Respondent owns 50 other domain names starting with “pro”. The fact that the Respondent registers domain names with a “pro” prefix suggests that the Respondent may not have been targeting the Complainant but registered the disputed Domain Name due the Respondent’s interest in “pro” domain names. As a result, the Panel cannot conclude that the Respondent was aware or should have been aware of the Complainant or the PROIBS trademark at the time of registration of the disputed Domain Name.

Furthermore, the Respondent offered the disputed Domain Name for sale for USD $194,888. An argument could be made that only the Complainant would be prepared to pay such a price, and so the Respondent is in fact targeting the Complainant. In some circumstances, the price of the disputed Domain Name could be a factor that may allow the panel to infer that because only a business of the size of the complainant could or would pay that price, the respondent is targeting the complainant. On the other hand, if the disputed Domain Name in fact is registered without knowledge of the complainant and otherwise in good faith, then setting a high price would be a matter purely for the respondent in view of its business plans. In the present case, if any such inference could arise, the Respondent provided credible evidence and a signed declaration to rebut any such inference that the Respondent was aware of the Complainant when registering the disputed Domain Name. The Panel also notes that the sales price of the disputed Domain Name was initially USD $8,000, which does not suggest that in 2011 the Respondent considered that the value of the domain name derived primarily from the Complainant’s trademark rights. On the balance of probabilities, there is no evidence presented by the Complainant to conclude that the Respondent intentionally targeted Complainant and its PROIBS trademark when the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in 2011.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: Brian Leventhal, Attorney at Law, P.C., United States

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

First, I want to highlight the excellent recital of the law of evidence in the UDRP as set out by the Panelist:

“An asserting party needs to establish that it is more likely than not that the claimed fact is true. An asserting party cannot meet its burden by simply making conclusory statements unsupported by evidence. To allow a party to merely make factual claims without any supporting evidence would essentially eviscerate the requirements of the Policy as both complainants and respondents could simply claim anything without any proof. For this reason, UDRP panels have generally dismissed factual allegations that are not supported by any bona fide documentary or other credible evidence. Snowflake, Inc. v. Ezra Silverman, WIPO Case No. DIO2020-0007; Captain Fin Co. LLC v. Private Registration, NameBrightPrivacy.com / Adam Grunwerg, WIPO Case No. D2021-3279.”

This is a great reminder for Panelists to keep this in mind when adjudicating cases.

Second, I also want to highlight the Panelists focus on what I consider the key element in a UDRP case:

“Generally speaking, a finding that a domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith requires an inference to be drawn that the respondent in question has registered and is using the disputed Domain Name to take advantage of its significance as a trademark owned by the complainant. Fifth Street Capital LLC v. Fluder (aka Pierre Olivier Fluder), WIPO Case No. D2014-1747.

…

In short, the Complainant has not shown with evidence why the Respondent would have known of and targeted it.

…

On the balance of probabilities, there is no evidence presented by the Complainant to conclude that the Respondent intentionally targeted Complainant and its PROIBS trademark when the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in 2011.”

The Panel noted that “the Complainant provided no factual evidence or arguments to support the Complainant’s assertion of bad faith.” As the Panelist correctly suggested, a Complainant must do more than merely assert targeting, but must prove it with evidence. The coincidence of a domain name and trademark alone is insufficient in some cases.

Thirdly, I want to highlight a very clear and plain recital of the law on domain name investing, as expressed by the Panelist:

“Dealing in domain names in the secondary market is a legitimate trading activity. By its very nature, it is speculative. A domainer usually has the intention of reselling domain names at a price in excess of the purchase price. Some domain names sell, and some sit on the shelf unsold; in either event, trying to make a profit by reselling domain names is not bad faith per se. Sage Global Services Limited v. Narendra Ghimire, Deep Vision Architects, WIPO Case No. DAI2023-0010.” [emphasis added]

Lastly, I want to highlight the Panelist’s nuanced understanding of domain name pricing in the UDRP:

“In some circumstances, the price of the disputed Domain Name could be a factor that may allow the panel to infer that because only a business of the size of the complainant could or would pay that price, the respondent is targeting the complainant.

On the other hand, if the disputed Domain Name in fact is registered without knowledge of the complainant and otherwise in good faith, then setting a high price would be a matter purely for the respondent in view of its business plans.”

Bookmark this case. It is an important example of how to approach domain name investing cases which showcases how a nuanced approach to the facts is required rather than a knee-jerk reaction and transfer.

Why Was the Respondent’s Website Considered to be “Passive Holding”?

Textron Innovations Inc. v. Robert Becker, NAF Claim Number: FA2404002095234

<icessna .com>

Panelist: Mr. David P. Miranda, Esq.

Brief Facts: The Complainant is the owner of the CESSNA marks that it licenses exclusively to Textron Aviation. The complainant holds several U.S. trademark registrations for the brand CESSNA, with the oldest one dating back to April 1, 1969. ‘Cessna Aircraft’, formed in 1927, is today owned and operated by Textron under its Textron Aviation business segment. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is not using the disputed Domain Name in connection with any bona fide offering of goods and services or for any legitimate or fair use because the disputed Domain Name does not resolve to an active website. Furthermore, the Respondent both registered and is using the domain name at issue in bad faith to intentionally disrupt the business of the Complainant and in an intentional attempt to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to its website.

The Respondent is a licensed Single and Multi-Engine Commercial pilot, a Certified Flight and Instrument Instructor, a licensed Airframe and Powerplant mechanic and he holds FAA Inspection Authorization. The Respondent contends that he has over 20 years of experience in the aviation industry and through a wholly owned company, he owns five Cessna aircraft. The Respondent further contends that his plans when registering the disputed Domain Name and expending significant web development costs (approx. $10,000) to date on the site hosted at the disputed Domain Name was to create a marketplace for third-party aviation professionals to be able to post Cessna aircraft, its parts and related services for sale. The Respondent’s website is currently operating in beta mode and is otherwise incomplete.

Held: The Complainant has met its initial burden of showing that the Respondent having no rights or legitimate interests in the domain name at issue and that its purpose for registering the disputed Domain Name is to utilize these domains to divert traffic to its website, capitalize upon the confusion that consumers will likely have when navigating to this domain and unfairly profit from these illegitimate and unauthorized uses of the CESSNA mark in this Domain Name. The passive holding of a domain name does not show a legitimate use or bona fide offering of goods or services. The Respondent’s contention that it has created a beta site does not sufficiently establish its rights or legitimate interests.

Regarding bad faith registration, the panels have found that registration of a confusingly similar domain with knowledge of a Complainant’s rights in a mark constitutes bad faith under Policy ¶ 4(b)(iii). Furthermore, the use of a confusingly similar domain name to compete with a complainant or to attract customers to a site for commercial gain to constitute bad faith use and registration pursuant to Policy ¶ 4(b)(iv). See, for example, MathForum.com, LLC v. Weiguang Huang, D2000-0743 (WIPO Aug. 17, 2000) finding bad faith under Policy ¶ 4(b)(iv) where the respondent registered a domain name confusingly similar to the complainant’s mark and the domain name was used to host a commercial website that offered similar services offered by the complainant under its mark.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Jeremiah A. Pastrick, Indiana, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Rachel Young Fields of Hunter, Maclean, Exley & Dunn, P.C., Georgia, USA

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: CESSNA is a well-known trademark. The addition of an “i” to the trademark within the Domain Name does indeed arguably fail to “mitigate the confusing use of the trademark” as the Panelist found. Moreover, use of a “confusingly similar domain name to compete with a complainant or to attract customers to a site for commercial gain” can indeed constitute bad faith use and registration as the Panel found. But is that the end of the inquiry?

Here, the Respondent was genuinely an experienced and certified pilot, flight instructor, and mechanic and indirectly owns five Cessna aircraft. Moreover, the Respondent expressly claimed that prior to notice of the dispute, he had expended approximately $10,000 on developing a website and in fact, the website exists and existed prior to notice of the dispute, albeit in “beta mode” and is currently incomplete. As such, these facts trigger a consideration of Paragraph 4(c) of the Policy which expressly states that a Respondent can demonstrate its rights and legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name if “before any notice to you of the dispute, your use of, or demonstrable preparations to use, the domain name or a name corresponding to the domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services”. Clearly the Respondent had made both use and demonstrable preparations to use the Domain Name as evidence by his website.

Why was this left totally unconsidered by the Panelist? Indeed, why did the Panelist expressly consider this to be a case of “passive holding” despite the existence of the Respondent’s website?:

“The passive holding of a domain name does not show a legitimate use or bona fide offering of goods or services. Respondent’s contention that it has created a beta site does not sufficiently establish its rights or legitimate interests”.

This was not passive holding. It was actual use. The Panelist’s conclusion therefore doesn’t make any sense and appears to mischaracterize and ignore the fact that a website existed. Moreover, the decision appears to ignore the safe harbor provisions of the Policy under Paragraph 4(c). Now, the Panelist could have possibly considered the Respondent’s website not to be “bona fide” use under Paragraph 4(c), but no such consideration was expressed in the decision. Panelists have a duty to follow the Policy, explain their reasons, and not write overly brief decisions which fail to credibly take into account the facts and arguments present.

Unfortunately, this does not appear to be the case here. That is not to say that the overall outcome was necessarily incorrect, but the route to getting there must be fair and also be perceived to be fair. Fairness requires a Panelist to adequately base its decision on the requirements of the Policy and to satisfactorily explain the basis for the decision in a manner which takes into account both the Policy and the facts and arguments raised by the parties.

Cybersquatting or a Genuine Business Dispute?

State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company v. Tommy Brooks, NAF Claim Number: FA2405002096979

<tommystatefarm .com>

Panelist: Mr. Terry F. Peppard

Brief Facts: The Complainant submits that since 1930, it has become and remains a prominent marketer of insurance products and financial services. The Complainant holds a registration for the service mark STATE FARM, on file with the USPTO (registered on August 22, 2017). The Complainant has done business online at the address <statefarm .com> since 1995. The Respondent is an independent contractor agent for the Complainant and registered the domain name <tommystatefarm .com> on February 9, 2024. The Complainant alleges that it has never authorized the Respondent to register the Domain Name or to use Complainant’s STATE FARM mark for purposes other than those specifically permitted under the agency agreement between them. The Complainant further alleges that the domain name resolves to a parked web page featuring click-through links to other web pages offering for sale various products and services, some of which are in competition with the business of the Complainant. The Respondent failed to submit a Response in this proceeding.

Held: The pivotal facts alleged in the Complaint are that the Complainant has never authorized Respondent to register the disputed <tommystatefarm .com> domain name or to use Complainant’s STATE FARM mark for purposes other than as specifically permitted under the agency agreement between them, and the domain name is not so permitted. Importantly, the document(s) constituting that agency agreement are not attached to the Complaint. From the review of the exceptionally spare contentions set out in the Complaint and accompanying papers, it is clear that this is not a dispute within the contemplation of the Policy, which is intended solely to address instances of “cyber-squatting,” by which is meant the abusive registration and use of Internet domain names.

Rather, this is a dispute as to the proper interpretation and application of a business agreement, which should be confided to the jurisdiction of the appropriate local or national courts. See, for example, Nintendo of America Inc. v. Alex Jones, D2000-0998 (WIPO November 17, 2000): “It is not the function of an ICANN Administrative Panel to resolve all issues concerning the use of intellectual property rights. Matters beyond the narrow purview of the Policy are for the courts…”. The Panel is aware that this dispute may now be brought before the appropriate court, and believes that it is prudent to leave the decision on its merits to such a decision-maker, with the benefit of a full evidentiary record and the ability to construe and interpret the contractual terms which will ultimately govern this dispute.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Sherri Dunbar of State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company, Illinois, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: I generally have a lot of respect of Panelists who take a restrained approach to the UDRP by deferring to the courts where a case exceeds the limited scope of the UDRP. As the Panel noted, the UDRP “is intended solely to address instances of “cyber-squatting” and not “the proper interpretation and application of a business agreement, which should be confided to the jurisdiction of the appropriate local or national courts”.

Here, the Respondent did not respond and the Domain Name resolved to a standard registrar parking page with insurance related PPC links. Conceivably, the Respondent may have used the Domain Name for email for his insurance brokerage business under contract with State Farm, the Complainant though it would have been very recent use since the Domain Name was only registered a four months ago on February 9, 2024. Nevertheless, there was no evidence of any usage of the Domain Name by the Respondent whatsoever, nor was there any explanation of why the Domain Name was selected by the Respondent. Ostensibly, it could have been registered to use for the Respondent’s insurance brokerage business, but this was not claimed, though arguably implicit.

On the other hand, the Complainant’s Complaint was “spare” according to the Panel, though it did apparently refer to an agency agreement between the parties that did not permit the Respondent to register a STATE FARM Domain Name.

So is this a case of cybersquatting or a business dispute outside the scope of the UDRP, as the Panelist found? At first this might seem like it should have been treated as a case of mere cybersquatting, considering no explanation or evidence of use was provided by the Respondent, despite being an agent of the Complainant and especially considering that such registration was apparently prohibited by the agency agreement. But the Panelist noted that given the business relationship between the parties as disclosed by the Complainant itself, the Complaint was insufficient. The Panel noted in particular (citing inter alia, Schneider Electronics GmbH v. Schneider UK Ltd., D2006-1039 (WIPO October 21, 2006) that:

In situations such as the present case, where the parties have entered into and maintained a long-standing commercial relationship, Panels tend to impose on the Complainant a heavier burden of proof for bad faith, generally requiring more comprehensive evidence than that which may be necessary in the typical dispute between unrelated adversaries. At a minimum, the Complainant must provide full disclosure of the history of the relationship, and in particular, the relevant agreements and contractual terms which have governed their joint enterprise…. It is also important to bear in mind that the Policy was designed to prevent cases of cybersquatting and it cannot be used as a means to litigate broader disputes involving domain names (citations omitted).

I think that the Panel was correct in that where there is a broader business dispute involving contracts and a longstanding relationship (as in the Schneider case), it is likely a dispute that is not properly dealt with by the UDRP. Nevertheless, the Schneider case was a fully defended proceeding where there were apparently numerous factual and legal questions involving a Distribution Agreement, a purported settlement, an incomplete record of contractual dealings, and an unexplained 6 year delay in raising an objection to the domain name. That led the Panelist in the Schneider case to find that the case is “most properly characterized as a dispute between parties formerly joined in a long-standing commercial relationship” and the termination raised “contested issues of fact and the construction of contractual provisions which go beyond the issue of cybersquatting”.

I think the Schneider case is therefore distinguishable from the present case as in that case, there were serious factual and legal issues raised by the Respondent, whereas here, there were no issues raised by the Respondent beyond the fact that the Complainant acknowledged that the Respondent was its agent. Now, that single fact alone could arguably give rise to the scope issue, but it is a close one. I think that something more than that fact could be required in order to determine that the case was outside the scope. On the other hand, the Complainant’s “sparse” Complaint might have led to the Panel cautiously punting the case because the Complainant left too many unknowns. On the other hand, had the Complainant provided additional information and documentation, that could have served to reinforce the nature of the dispute as being a contractual dispute rather than cybersquatting. It is difficult to say what the right decision was here. I can see both perspectives on it, and when there are two perspectives, one should probably treat it as an unclear case to be dismissed as the Panel did in this case. On the other hand, without the Respondent coming forward with an explanation, the mere fact that he is an agent is not necessarily inconsistent with also being a cybersquatter. A tough call.

Appropriately Deferring to the Courts

Z and J Enterprise Inc. v. andrew fusco, NAF Claim Number: FA2405002098362

<claimshield .com>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith

Brief Facts: The US-based complainant has offered loss recovery and insurance consultation services under the CLAIM SHIELD brand since January 1, 2017. It owns a trademark for CLAIM SHIELD with the USPTO, registered on December 24, 2019. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has not used the Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services. Rather, the Respondent is passing off as the Complainant or affiliated with the Complainant in order to divert consumers to its competing services. The Complainant further alleges that the respondent registered and uses the domain name in bad faith, having acquired it after the complainant’s first use of the CLAIM SHIELD mark. Additionally, given the offering of insurance services Respondent had actual or constructive knowledge of the Complainant’s rights in the CLAIM SHIELD mark at the time of registration.

The Respondent contends that he is a public loss adjuster and consultant with 31 years of experience in the insurance industry. He acquired the disputed Domain Name from the previous owner to offer insurance services under the CLAIM SHIELD name through Claimshield LLC and Claimshield Holdings Inc. As a result, the Respondent is commonly known by the Domain Name as the Domain Name aligns with its corporate entity. The Respondent further contends that the Respondent is not disrupting the Complainant’s business but making a bona fide offering of services from its website under a Domain Name which corresponds to its registered company name in Puerto Rico.

Held: The Respondent’s Website does not either explicitly or implicitly make any reference to the Complainant or otherwise suggest an affiliation (other than the shared use of the mark/mark elements “CLAIM SHIELD” for insurance services). In particular, the Panel rejects Complainant’s unsupported assertions that the Respondent’s Website mimics the Complainant’s Website (or the device mark displayed on the Respondent’s Website is in any way similar to the device elements in the CLAIM SHIELD Mark). The Panel accepts the Respondent’s submission that the terms “claim” and “shield” are commonly used in the insurance industry and hence there is a reason for the use of the “claim shield” term absent any connection with the Complainant and acknowledges that the evidence of the Respondent’s other domain name registrations of marks containing the “claim” element supports the submission that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name for its inherent meaning rather than any connection with the Complainant. The Panel also notes that there is no other evidence of any conduct engaged in by the Respondent that suggests the use of the Domain Name is anything other than for a bona fide offering of services, such as phishing e-mails, misleading statements, a pattern of conduct of abusive registrations or the like.

The Panel has concerns with the extent of the Respondent’s evidence of its business, given that the Respondent’s Website is a fairly limited website with limited functionality. While acknowledging the limitations of the Respondent’s evidence, in the Panel’s evaluative judgement of the evidence before it, the Panel is not satisfied that the Respondent lacks rights and legitimate interests. The Panel considers that any questions of fact regarding the nature and legitimacy of the Respondent’s business and company registration are better resolved in a venue that has explicit forensic powers which a Panel under the Policy does not have. The Panel acknowledges that the Respondent’s conduct may infringe Complainant’s CLAIM SHIELD mark (while noting that the CLAIM SHIELD mark is a device mark rather than a word mark) or amount to passing off and the Panel wishes to make it clear that other remedies may be available to the Complainant in a different forum, and that nothing in this decision should be understood as providing a definitive finding on the respective mark rights of the parties, beyond the narrow question determined under this proceeding. The Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy is designed to deal with clear cases of cybersquatting.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Neil Peluchette of Taft Stettinius & Hollister LLP, Indiana, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Jean Vidal-Font, Esq. of Ferraiuoli LLC, Puerto Rico, USA

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: I think the Panelist handled this case exactly right. The Panelist gave credit to the Respondent for having an apparently bona fide business as a result of its website but expressed concerns regarding the extent of it. The Panelist also noted that there could be an issue of trademark infringement. But to the Panelist’s credit, he took an appropriately restrained approach and did not wade into a dispute which deserved the more robust procedures and scope available via a court case.