We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (Vol. 3.21), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with commentary from our Director, Nat Cohen and General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch.

‣ Typo Domain Name Used for Genuine Criticism (vallhallan .com *with commentary)

‣ What is the Standard for “Plausibility” when the Disputed Domain Name is Passively Held? (fbsolution .info *with commentary)

‣ Respondent Attempted to Impersonate the Complainant (booking-skyscanner .com *with commentary)

‣ Was Respondent’s Explanation Credible? (indiaknowledgeacademy .org *with commentary)

‣ Language for the Proceedings: Fundamental Fairness is of Paramount Importance (ruckusnow .com *with commentary)

Complimentary CIIDRC Webinar Series on Friday, May 26, 2023 at 1:30 pm EST

Register at: https://bit.ly/3VAJB6C

——-

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

Typo Domain Name Used for Genuine Criticism

Valhallan, LLC v. Casey Strattan, WIPO Case No. D2023-0977

<vallhallan .com>

Panelist: Mr. Robert A. Badgley

Brief Facts: The Complainant does not describe its business in the Complaint, however, the Complainant owns a UK trademark for VALHALLAN registered on April 11, 2022. Additionally, it filed a USPTO application on February 8, 2022, in connection with “entertainment in the nature of e-sports competitions”, with a claimed date of first use in commerce of January 21, 2022. According to the Complainant, this USPTO application “is still pending.” The Complainant claims, without any supporting evidence, that it “has clearly demonstrated a right to a common law trademark in the US.” The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 18, 2022, (ten days after the Complainant filed its USPTO trademark application) and resolves to a website entitled, “VALHALLAN FRANCHISE REVIEW.”. Below this header is the large-print text: “OWNED BY AN ASSHOLE”. More text appears below that disclaims affiliation with the Complainant and contains further criticism of the Complainant and its business.

The Respondent contends that he was a franchisee of a company that the Complainant’s president owned before it “failed”. Prior to initiating this proceeding, Complainant’s president had approached the Respondent (through the latter’s domain broker) with an offer to purchase the Domain Name for USD $250. The Respondent refused with a statement that he would sell the Domain Name for USD $10,000, to which the Complainant made two more offers, including the final offer for USD $5,000. The Respondent challenges Complainant’s alleged common law trademark rights and asserts that he has the right to criticize the Complainant and its president, to make prospective consumers and franchisees aware of what the Respondent believes to be unscrupulous business practices and asks for a finding of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking against the Complainant, largely due to the allegedly false statements and factual omissions contained in the Complaint.

After the Complaint was commenced, the Complainant’s president sent at least two emails to the Respondent, one threatening to file a federal lawsuit against the Respondent (with the president’s comment that “I have unlimited time and resources”), and the other rescinded the USD $5,000 offer. In the latter missive, the president offered to withdraw the UDRP complaint if the Respondent would sign a non-disparagement and non-interference agreement and transfer the disputed Domain Name. The Respondent further contends that the Complainant omitted from its Complaint that the USPTO took a “Non-final Office Action” on November 23, 2022, which refused the Complainant’s application to register VALHALLAN. This USPTO notice, which was addressed to the Complainant’s counsel in this proceeding, confirmed that the application had been rejected.

Held: The Respondent is obviously no fan of Complainant’s president, and he makes this as clear as possible on the website. The unflattering headline, the comment, and the content make it clear that the site is unaffiliated with the Complainant. The Panel also notes for completeness that this is not a case where the disputed Domain Name is identical to the concerned mark (which may trigger the impersonation test, e.g., as described in section 2.5.1 of the WIPO Overview), but is a typo. The Panel finds Respondent’s free-speech criticism of the Complainant and its president – using a typo domain name – to be genuine and not pretextual. The fact that the Respondent rebuffed the Complainant’s unsolicited offers to buy the Domain Name, and the Respondent’s setting a price of USD $10,000 as an asking price, does not alter this determination. To the extent it matters, it was the Complainant who approached the Respondent to discuss a sale, and not the other way around.

Moreover, albeit somewhat as an aside (noting that this is a typo case, and there is no evidence it presents a pretext for cybersquatting), in its apparent reply to the USPTO’s rejection of the VALHALLAN trademark application, the Complainant itself states that there is little chance of consumer confusion (between the VALHALLAN mark and the existing VALHALLA VALKYRIES mark) because the Complainant’s customers are sophisticated and by implication not susceptible to confusion. The Complainant did not establish that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests. Hence, the Panel need not address the Bad Faith issue, given its ruling above that this case does not present a situation of cybersquatting masked as free speech.

RDNH: The Panel finds that the Complainant indulged in Reverse Domain Name Hijacking given that the Complainant offered no evidence to support its bald claim that it has “clearly demonstrated” common law rights in the U.S. for the VALHALLAN mark. Further, the Panel notes that the Complainant entirely omitted the fact that the Complainant initiated discussions with the Respondent about a possible sale of the Domain Name and that the Respondent thrice refused to sell. This omission is not as serious, in this case, as the failure to disclose the USPTO refusal notice, but it underlines an apparent strategy by the Complainant here to keep the Panel on a “need to know” basis.

Most importantly to this finding, the fact that Complaint omitted the USPTO refusal from its pleading, and even referred to the USPTO application as “still pending,” is, to put it most gently, highly misleading. It is not the job of a UDRP complainant’s counsel to make out the Respondent’s case for him, but a modicum of candor is required, particularly given the lack of discovery, cross-examination, and so forth in UDRP cases. The represented Complainant (indeed, the same counsel who received the USPTO refusal notice), has abused this process by concealing the true status of the USPTO application. If there had been no Response filed in this action, the Panel would have been under the false impression that the USPTO application was sailing along smoothly, with no obstacles in its way.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

Interestingly, the Panelist distinguished between a domain name that is identical to a Complainant’s mark and a typo of it, noting that an “impersonation” test only applies “where the disputed domain name is identical to the concerned mark”. The Panelist cited Section 2.5.1 of the WIPO Overview for this and indeed the Overview does refer to “identical” marks only when evaluating risk of implied affiliation: “Generally speaking, UDRP panels have found that domain names identical to a complainant’s trademark carry a high risk of implied affiliation” [emphasis added]. I don’t think however, that this is a meaningful distinction as surely if a typo of a complainant’s brand was used to impersonate a complainant, the fact that the domain name was not “identical” would not avoid a finding of impersonation or bad faith use. I think rather, that the Panelist expressly made this observation “for completeness” and this finding was ultimately not what the Panelist’s decision turned on. Nevertheless, this serves as a good reminder that the WIPO Overview has not been updated since 2017, is not the product of wide stakeholder input and consensus, and is not authoritative. The Overview can be very helpful for guiding panelists but it is no substitute for the actual case law. I often see the Overview misused by panelists quoting it like it was actual law when in reality it is a secondary source and reflects an incomplete though often useful perspective of the authors.

In any event, to Panelist Robert Badgley’s credit in this case, he found that the Respondent’s free speech criticism of the Complainant and its president using a typo domain name, to be genuine and not pretextual. I think that this may be the best yardstick from which to judge criticism cases; Is the criticism genuine or pretextual. If it is pretextual, that would usually mean that this is a case of cybersquatting, but if it is genuine, it is not cybersquatting – and the UDRP only addresses cybersquatting. As a result, any non-cybersquatting cases are not within the scope of the UDRP and must be dismissed, regardless of whether the content is pejorative, arguably defamatory, inappropriate, or whatnot. Those non-cybersquatting complaints are for courts to make, not UDRP panelists.

Now, some may argue that if the domain name is identical, then that is a bridge too far and that is where the line should be drawn regardless of whether it is used for genuine criticism. As noted in Nat Cohen’s article, “Does the UDRP Interfere With Free Speech Rights? – TheStopSpectrum.com Decision” (Cohen, CircleID, December 19, 2022 at footnote #2), there is a sharp divergence of views on this issue, as also noted in section 2.6.2 of the WIPO Overview: “In certain cases involving parties exclusively from the United States, some panels applying US First Amendment principles have found that even a domain name identical to a trademark used for a bona fide noncommercial criticism site may support a legitimate interest”. I am sympathetic to the view of some panelists that an identical domain name for criticism is a bridge too far and is unfair to the Complainant. This view often considers “initial interest confusion”, i.e. the impression that the identical domain name makes even before visiting the associated website. Nevertheless, even if this is considered “unfair”, that is a matter for courts and not for the UDRP, simply because this is not “cybersquatting” as understood by the UDRP per se. Rather, when even an identical or typo domain name is used for genuine criticism, i.e. “legitimate noncommercial or fair use”, then the Respondent has safe habor under Paragraph 4(c)(iii) of the Policy and has “demonstrated” rights and legitimate interest:

How to Demonstrate Your Rights to and Legitimate Interests in the Domain Name in Responding to a Complaint.

Any of the following circumstances, in particular but without limitation, if found by the Panel to be proved based on its evaluation of all evidence presented, shall demonstrate your rights or legitimate interests to the domain name for purposes of Paragraph 4(a)(ii):

…

(iii) you are making a legitimate noncommercial or fair use of the domain name, without intent for commercial gain to misleadingly divert consumers or to tarnish the trademark or service mark at issue.

So to reiterate, the yardstick should be, whether the criticism is genuine or pretextual. Otherwise it is outside the limited scope if the UDRP. Moreover, as I noted in my Comment on SouthWoke .com case in Volume 3.20, panelists should consider themselves ill-suited to adjudicate this kind of more subjective, complex, and fraught dispute which may involve national free speech law, regardless of whether the content is pejorative or derogatory.

Lastly, regarding the RDNH finding in this case, the Panelist aptly said that while “it is not the job of a UDRP complainant’s counsel to make out the respondent’s case for him, but a modicum of candor is required, particularly given the lack of discovery, cross-examination, and so forth in UDRP cases”. Sometimes counsel for complainants as well as counsel for respondents, get tripped up on this, incorrectly believing that since this is an adversarial system that it is up to the other side to clear up any false impressions left by one’s submissions. That is not the case with the UDRP as the certifications required under the Rules require a higher standard than may otherwise exist outside of the UDRP:

“Complainant [or Respondent] certifies that the information contained in this Complaint is to the best of Complainant’s knowledge complete and accurate, that this Complaint is not being presented for any improper purpose, such as to harass, and that the assertions in this Complaint are warranted under these Rules and under applicable law, as it now exists or as it may be extended by a good-faith and reasonable argument.”; and

Practice Tip: After many years of practice I have learned that being forthcoming with imperfections or weaknesses in one’s case and addressing them is far preferable than concealing them. UDRP Panelists are usually quite experienced and adept at sniffing out lack of candour and will treat an entire submission with scepticism where a lack of candour even on one aspect has been found. For complainants, a lack of candour sometimes occurs in relation to disclosing similar third party trademarks, changes in corporate names or structure, lapses in trademark registrations, and as seen in this case, trademark office refusals. For Respondents, a lack of candour sometimes occurs in relation to disclosing the registration date when it is different than the creation date and the reason for registering the domain name. I have found that panels will indirectly give credit and respect a party that is forthcoming and making an extra effort in this regard is well worth it, not just because of the ethical obligations to do so but also because it can actually help.

What is the Standard for “Plausibility” when the Disputed Domain Name is Passively Held?

FB SOLUTION v. Nurcan Öztürk, WIPO Case No. D2023-1110

<fbsolution .info>

Panelist: Dr. Kaya Köklü

Brief Facts: The French Complainant, founded in 2004, is active in baking and delivery of bread, pastries and cakes to professional customers such as airline and railway catering companies and to hotels and restaurants in various markets. The Complainant owns various word and figurative trademark registrations for FB SOLUTION, among others, the European Union Trademark (registered on February 21, 2006) for the word mark FB SOLUTION. Since 2010, the Complainant further owns and operates various domain names incorporating its FB SOLUTION trademark, such as <fbsolution .fr> and <fbsolution .com>. The Turkish Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name on September 12, 2022, not associated with an active website.

Held: The Complainant makes available prima facie evidence that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests, particularly no license or alike to use the Complainant’s FB SOLUTION trademark in a confusingly similar way within the disputed Domain Name. The Panel notes that the nature of the disputed Domain Name carries a high risk of implied affiliation or association, as stated in section 2.5.1 of the WIPO Overview, considering that the disputed Domain Name is identical to the Complainant’s trademark.

The Panel is convinced that the Respondent was aware of the Complainant’s FB SOLUTION trademark when registering the disputed Domain Name in September 2022. At the date of registration, the Complainant’s FB SOLUTION trademark was already registered and used for many years. Bearing in mind the inherently misleading nature of the disputed Domain Name, it is obvious to the Panel, that the Respondent deliberately chose the disputed Domain Name to target the Complainant and mislead Internet users who particularly are searching for information on the Complainant and its provided goods and services. Consequently, the Panel has no doubt that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith.

With respect to the use of the disputed Domain Name in bad faith, the disputed Domain Name still needs to be linked to an active website. Nonetheless, and in line with the previous UDRP decisions (Telstra Corporation Limited v. Nuclear Marshmallows, WIPO Case No. D2000-0003) and section 3.3 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, the Panel believes that the non-use of a domain name does not prevent a finding of bad faith use. Applying the passive holding doctrine as summarized in section 3.3 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, the Panel believes that the Complainant’s FB SOLUTION trademark is sufficiently distinctive and assesses that the composition of the disputed Domain Name, which fully incorporates the Complainant’s FB SOLUTION trademark, is inherently misleading. In view of the Panel, this makes any good faith use of the Complainant’s FB SOLUTION trademark within the disputed Domain Name unlikely and implausible.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Scan Avocats AARPI, France

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Comment by Nat Cohen. Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of https://UDRP.tools/ and https://www.rdnh.com/, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

Is the “passive holding” jurisprudence dating back to the earliest days of the UDRP due for an update?

The Complainant in the <fbsolution .info> dispute is a French-based bakery company, FB Solution, which has operations across much of the globe, including a related company based in Hong Kong. The Complainant alleges that the disputed domain name, <fbsolution .info>, despite being inactive, was registered and is being used in bad faith to target its mark. The Panel in this dispute, therefore, looked to the consensus approach to resolving disputes involving “passively held” domain names.

The question of when “non-use” can be considered “use” for the purposes of the Policy was addressed in the third-ever decision issued by WIPO. In Telstra Corporation Limited v. Nuclear Marshmallows, WIPO Case No. D2000-0003, (“Telstra”), the disputed domain name, telstra.org, was inactive. Panelist Andrew Christie held that an inactive domain name could be found to meet the criteria for bad faith registration and use if five “particular circumstances” were present. The most notable of these circumstances is that “it is not possible to conceive of any plausible actual or contemplated active use of the domain name by the Respondent that would not be illegitimate”. This is a sensible approach since if it is not possible to conceive of any use of the domain name that would be legitimate then, even in its inactive state, it is reasonable to infer that the disputed domain name was registered in bad faith to target the Complainant’s mark.

Telstra is still followed today. It is one of the most influential decisions in all UDRP jurisprudence and has been cited in thousands of other decisions. Unsurprisingly, the consensus view on passively held domain names as presented in section 3.3 of the WIPO Overview 3.0 is essentially a restatement of Telstra. The Overview renders Telstra’s lack of plausibility criterion as, “the implausibility of any good faith use to which the domain name may be put”.

Telstra’s influence is manifested in the 12 cases that WIPO lists as relevant cases for its statement of the consensus approach towards passive holding as laid out in Section 3.3 of the Overview. Telstra is listed first. Most of the other listed cases directly cite Telstra. The ones that don’t directly cite Telstra circularly cite back to the passive holding section of the Overview that is based on Telstra. (The one exception is a case where the primary issue is not passive holding but domain names that precede the Complainant’s trademark rights.)

The essential criterion used to assess bad faith use of an inactive domain name has survived from the earliest days of the UDRP to the present day. That essential criterion is whether it is plausible that the inactive domain name could be put to legitimate use.

Yet absent from Telstra and from the Overview is clear guidance on how plausibility is to be determined, especially in the absence of a response. On what basis should a panel determine whether it is “possible to conceive” of a legitimate use or whether there is “the implausibility of any good faith uses”?

A Panel is faced with two choices for determining plausibility. A Panel can look inward and confer with itself. Or a Panel can look outward and observe in the real world whether terms that are similar to the disputed domain name are being put to legitimate, good faith uses independently of any reference to the Complainant’s marks.

In the <fbsolution .info> dispute, the Panel chose to look inward. It conferred with its own mind and determined it had “no doubt that the Respondent has registered the disputed domain name in bad faith”, that the <fbsolution .info> domain name is “inherently misleading” and that any possible good faith use of <fbsolution .info> is “unlikely and implausible”. Based on this assessment, the Panel found that the domain name was registered and used in bad faith and ordered the cancellation of the Respondent’s rights to the disputed domain name and that the disputed domain name be transferred to the Complainant.

If instead, the Panel had looked to the real world to determine the plausibility of a good faith use for the domain name <fbsolution .info>, the Panel would have found many examples of legitimate uses for “FB Solution” unrelated to the Complainant.

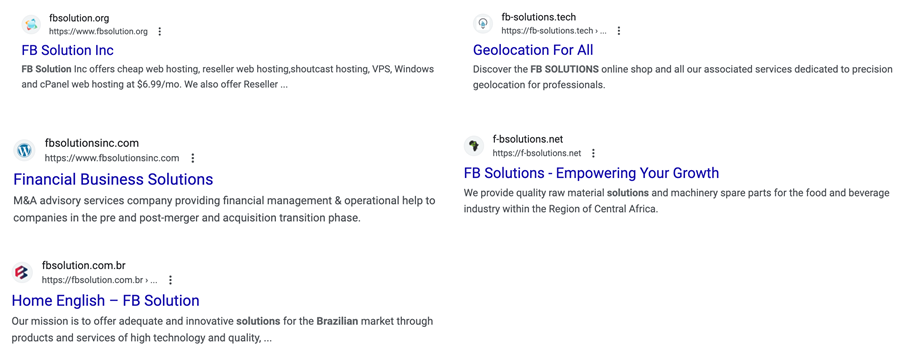

If the Panel had conducted a Google search on “FB Solution” it would have found the results:

If the Panel had conferred with the free DotDB.com database for domain names that start with “fbsolution”, it would have discovered that “fbsolution” is registered in 15 extensions, some associated with the Complainant and others associated with independent third parties including companies appearing in the Google results above:

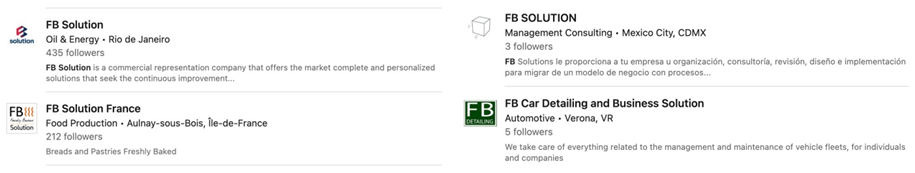

If the Panel had conducted a search on LinkedIn it would have found some additional evidence of third-party use:-

This brief investigation would have demonstrated, well beyond a balance of probabilities standard, that there are indeed many plausible legitimate, good faith uses to which the domain name <fbsolution .info> could be put, such that the circumstances for finding that a passively held domain name was registered and used in bad faith are not met here and that a transfer is not justified.

All of this information was available to the Panel with less than three minutes of effort.

Yet this research itself raises difficult questions. When is it appropriate for a Panel to conduct independent research? Is it appropriate for a Panel to make a case that the defaulting Respondent should have made for itself?

I believe that the answer to these questions is inherent in the jurisprudential consensus. The plausibility of whether a term can be put to a legitimate good faith is not determined by a Panel searching its own mind when the Panel may not have the necessary information, but only by the Panel conducting a real-world search of how that term is actually used. To do otherwise would mean the Panel is derelict in its duty to accurately determine the plausibility of a legitimate use for the domain name. The consensus approach relying on “plausibility” demands a real-world assessment of that plausibility.

A failure to look to the real world to determine the plausibility that a disputed domain name could be put to a legitimate, good-faith use would undermine the credibility and reliability of the UDRP. To offer an analogy, if someone who is entrusted with the considerable power and responsibility of a Panelist and yet is unfamiliar with rap music is asked to determine the plausibility that Travis Scott is a popular rapper and that person answers, “Well, I’ve never heard of Travis Scott, therefore, I have no doubt that it is implausible that Travis Scott is a popular rapper”, such an approach would be less credible than performing a Google search that would instantly provide the information that Travis Scott is indeed one of the most popular rappers in the world.

Yet this raises another difficult question. How is a Panel to know what it does not know? In other words, how is a Panel able to self-assess that it does not possess sufficient knowledge to make an assessment about plausibility when it is not even aware of its own ignorance?

In the <fbsolution .info> dispute, the Complainant FB Solution is apparently well-known in Europe where the Panel is based and it was likely the only business named “FB Solution” that the Panel had ever come across and “FB Solution” is not a dictionary term nor a descriptive phrase, and the Respondent had not replied to present any contrary evidence, so it is not surprising that the Panel based on its own experience had “no doubt” that the Respondent was intending to target the Complainant with its registration of the <fbsolution .info> domain name.

Yet from the perspective of a U.S.-based domain name investor, when I saw <fbsolution .info> listed on the daily report of WIPO decisions as a transfer, I thought it notable enough that it deserved further investigation. I had no current awareness of the Complainant. More to the point, as a domain name investor, when I see the domain name <fbsolution .info>, I see a two-letter acronym combined with a common business term, which I view as an inherently non-distinctive and inherently appealing domain name that could and would appeal to a wide variety of businesses. Indeed, as the research above demonstrates, such terms are widely used.

It is not in the best interests of the credibility and reliability of the UDRP as a Policy that the plausibility of a legitimate use for a passively held domain name be determined by a Panel that wilfully keeps itself in ignorance, but instead, the Panel should inform itself of the plausibility of such use by investigating it. In doing so, the Panel is not overstepping by conducting independent research to determine the accuracy of evidence submitted by the parties to the dispute but is instead properly fulfilling its obligations to knowledgeably apply the Policy as the Policy has been interpreted under the “passive holding” doctrine regarding the plausibility of a legitimate use for the disputed domain name.

Panels when assessing the plausibility of legitimate use in passive holding cases should not rely merely on their own perceptions but should conduct limited independent research to determine whether there is third-party use of the term in question.

Respondent Attempted to Impersonate the Complainant

Skyscanner Limited v. Wei Meng Chan, WIPO Case No. D2023-1073

<booking-skyscanner .com>

Panelist: Mr. Federica Togo

Brief Facts: The Complainant sells online travel agency services, which are available in over thirty languages and in seventy currencies. The Complainant uses the domain name <skyscanner .net> which resolves to its official website where it offers its services as a global travel search site. The Complainant is the registered owner of several trademarks for the term SKYSCANNER and claims that it enjoys a global reputation in its trademark. The registered marks include International Trademarks registered on March 3, 2006, and on December 1, 2009, respectively. The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 14, 2023, and resolved to a website allegedly offering its services as a global travel search site and reproducing without any authorization the Complainant’s trademark and logo which are identical to those displayed on the Complainant’s website.

The Complainant alleges that it is implausible that the Respondent was unaware of the Complainant when it registered the disputed Domain Name since it is well-known worldwide and the website to which the disputed Domain Name resolves implies that the services provided on it originate from the Complainant. There is no plausible explanation for the Respondent posing as the Complainant’s business, other than to deceive consumers into procuring travel arrangement services under the mistaken impression that they are procuring them from the Complainant. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The disputed Domain Name is clearly constituted by the Complainant’s registered trademark SKYSCANNER and the term “booking”, which clearly refers to the Complainant’s core business, tending to suggest sponsorship or endorsement by the Complainant. The Panel finds it most likely that the Respondent selected the disputed Domain Name with the intent to attract Internet users for commercial gain, which is confirmed by the content of the website to which the disputed Domain Name resolved. Such composition of the disputed Domain Name cannot constitute fair use if it effectively impersonates or suggests sponsorship or endorsement by the trademark owner (see section 2.5.1 of the WIPO Overview 3.0). This Panel finds, in the circumstances of this case, that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

In terms of paragraph 4(b)(iv) of the Policy, the Respondent by using the disputed Domain Name has intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to its website or other online location, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or endorsement of its website or location or of a product or service on its website or location. It is the view of this Panel that these circumstances are met in the case at hand. It results from the Complainant’s documented allegations that the disputed Domain Name resolved to a website allegedly promoting similar services to those of the Complainant and reproducing without any authorization the Complainant’s trademark and the logo.

Consequently, the Panel is convinced that the Respondent also knew that the disputed Domain Name included the Complainant’s trademark when it registered the disputed Domain Name. Lastly, the circumstances surrounding the disputed Domain Name’s registration and use confirm the findings that the Respondent has registered and is using the disputed Domain Name in bad faith (see WIPO Overview 3.0 at section 3.2.1).

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Lewis Silkin LLP, United Kingdom

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Why is this case noteworthy? For a kind of a funny reason. When you see the domain name, booking-skyscanner .com, what jumps out at you first? The SKYSCANNER trademark? Or how about the BOOKING trademark? For me it was both, as I recognized two respective trademarks in the domain name. Now, BOOKING alone is only a registered word mark of Booking.com BV, in one country, France according to the WIPO Global Brand Database, and the rest of its numerous marks are mainly for BOOKING.COM, so perhaps this is not the greatest example of a case where a disputed domain name includes two distinct brands owned by two distinct parties. But those cases would be interesting and if you are aware of any, please email me to let me know at Zak@InternetCommerce.org. I vaguely recall such cases being discussed at a WIPO workshop.

Was Respondent’s Explanation Credible?

The Knowledge Academy Holdings Limited v. Fal Pandya, WIPO Case No. D2023-0877

<indiaknowledgeacademy .org>

Panelist: Dr. Kaya Köklü

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a holding company of The Knowledge Academy Limited, which was incorporated in 2009 and is a provider of training solutions to the corporate, public sector, multinational organisations, and private individuals. The Complainant is the owner of THE KNOWLEDGE ACADEMY trademark, which is registered in various jurisdictions, including in the United States (registered on February 6, 2018), where the Respondent is reportedly located. The Complainant owns and operates domain names in .com and .co.uk extensions comprising its trademark. The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 20, 2023, and resolves to a default website of the Registrar. The Respondent did not submit any formal response.

In a short email communication, the Respondent merely stated that it believes that the disputed Domain Name is distinctly different from the Complainant’s trademark. Further, the Respondent alleged by email, that its main purpose is to use the disputed Domain Name for teaching about the ancient civilization of India. In a later communication, the Respondent merely indicated that it wished to discuss the case, however but did not provide any formal response to the Complainant’s contentions.

Held: The Respondent’s brief allegation in its email communication of March 13, 2023, that it intends to use the disputed Domain Name for teaching on the “ancient civilization of India” is assessed by the Panel as a merely self-serving and unfounded assertion by the Respondent. The Panel is convinced that, if the Respondent had legitimate purposes in registering and using the disputed Domain Name, it would have substantially responded. At the date of registration, the Complainant’s THE KNOWLEDGE ACADEMY trademark was already registered, used, and widely known, including in the United States, where the Respondent is reportedly located. Therefore, the Panel concludes that the Respondent deliberately attempted to create a likelihood of confusion among Internet users and/or to free ride on the goodwill of the Complainant’s THE KNOWLEDGE ACADEMY trademark.

Furthermore, the Panel finds that the Respondent is using the disputed Domain Name in bad faith, even though the disputed Domain Name is linked to a default page of the Registrar only. In line with the opinion of numerous UDRP panels before (e.g., Telstra Corporation Limited v. Nuclear Marshmallows, WIPO Case No. D2000-0003) and section 3.3 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, the Panel believes that the non-use of a domain name does not prevent a finding of bad faith use. Applying the passive holding doctrine as summarized in section 3.3 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, the Panel assesses the Complainant’s THE KNOWLEDGE ACADEMY as sufficiently distinctive, so that any good-faith use of the Complainant’s trademark in the disputed Domain Name (being the mark plus a geographical term) by the Respondent appears to be unlikely. Taking the facts of the case into consideration, the Panel concludes that the disputed Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Michelmores LLP, United Kingdom

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

The Panelist inter alia stated that, “the Panel particularly accepts the failure of the Respondent to submit a substantive response to the Complainant’s contentions as an indication for bad faith”. It is important to put this statement in context. In this case, the Respondent did respond, but didn’t provide more than a “brief and unsubstantiated allegation with no evidence”, by email that it “intends to use the disputed domain for teaching about the ancient civilization of India”. As such, I can appreciate the Panelist’s conclusion that this was insufficient to overcome the Complainant’s allegations in the circumstances of this case. Nevertheless, this wasn’t a “no response” case, but rather an ‘inadequate response case’. In an inadequate response case such as this, it can be reasonable to draw the inference that had the Respondent something more persuasive to say or had the Respondent supporting evidence, that the Respondent would have included it in its otherwise paltry and inadequate response. But that kind of inference is different than drawing an inference that ‘failure to file any response is necessarily an indication of bad faith’. If failure to file a response could be equated with bad faith, then any no response case could result in transfer, regardless of the evidence that the Complainant submitted. For helpful information on how panelists should handle ‘no response’ cases, please see “UDRP Panelists: Getting the Standard Right Where No Response is Filed” (Muscovitch and Cohen, CircleID, March 7, 2019).

Language for the Proceedings: Fundamental Fairness is of Paramount Importance

Arris Enterprises LLC v. luo wen qiang, NAF Claim Number: FA2304002041165

<ruckusnow .com>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith

PRELIMINARY ISSUE: Language of Proceeding: The Complainant has requested that the language of the proceeding be English, however, the language of the Registration Agreement, in this case, is Chinese. It is established practice to take UDRP Rules 10(b) and (c) into consideration for the purpose of determining the language of the proceeding to ensure fairness and justice to both parties. Convenience and expense are important factors in determining the language of a UDRP proceeding. Of paramount importance, however, is fundamental fairness. Requiring a party to conduct a UDRP proceeding in a language in which it is not proficient enough to enable it to do so, to understand the claims and defences asserted by the other party and to assert its own claims and defences, is simply not fair.

In this case, the registration agreement is in Chinese, the website to which the Domain Name resolves to appear to be inactive and the Respondent is based in China. The Complainant provided no evidence of the Respondent’s proficiency in English. The Complainant has merely asserted that the Respondent is capable of understanding English because the Domain Name consists of two English words (“rukus” and “now”) and the Respondent had to have sufficient familiarity with English to select those particular characters for registration. It is perfectly possible, with the aid of a dictionary, to identify words that exist in another language without having proficiency in that language. The Complainant’s assertions do not amount to evidence of a level of proficiency sufficient to enable a party to participate in a contested administrative proceeding in any meaningful or effective way.

Held: The Panel finds that the Complainant failed to produce sufficient evidence demonstrating that the Respondent has the capacity to understand the English language. If the English Language is adopted as the language of the proceedings, it would fail to comport with the Chinese language requirement in the available Registration Agreement and result in substantial prejudice towards the Respondent. The Complainant’s request for these proceedings to continue in English is DENIED.

Under the circumstances present in this case, the Panel concludes that ordering the Complaint to be translated into Chinese and proceeding from this point in Chinese, in which the Panel is not proficient, would be neither efficient nor productive. Accordingly, the Panel orders that the Complaint be dismissed, without prejudice. The Complainant may if it so desires file a new Complaint and proceed in the Chinese language, or provide persuasive, competent evidence that the Respondent is proficient in English.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: William Schultz of Merchant & Gould, P.C., Minnesota, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Much more could be written about this interesting subject matter, but for now I will focus on how the the Panelist has taken a decidedly different approach than usual, to ‘language of proceedings’. Often, a Complainant trying to get around the language of the registration agreement will simply say that ‘given the domain name is in English characters, the Respondent must know English, so lets proceed in English’.

More often than not, a Panel will accept such an argument and allow the dispute to proceed in English, especially in the absence of a response. Sometimes allowing the Complaint to proceed in English despite the language of the registration agreement may be a result of considering the merits of the case itself. For example, if the case appears to be a clear cybersquat with no response, how important is it that the Respondent have a good working knowledge of English? Moreover, if the Notice of Complaint was sent in the language of the registration agreement and still resulted in no response, does the consideration of expense and convenience tilt the balance in favor of proceeding in English? Is there an obligation of registrants not to mess around with famous marks in English if they are not prepared to face a UDRP in English? These are all valid considerations. On the other hand, a Panelist must not prejudge a case before giving the Respondent a fair opportunity to respond, and knowing enough English to register an English domain name does not by any means prove that the Respondent has sufficient capacity to respond to sophisticated legal English and ultimately the objective of the Rule is to afford the Respondent an opportunity to defend in its own language.

I think it is accurate to say that panelists have generally become a bit too loose with permitting a proceeding to be conducted in a language other than the language of the registration agreement. The default is the language of the registration agreement, and even taking into account the factors of “convenience and expense” as the Panelist in this case did, it is still incumbent upon the Complainant to provide a sufficient argument with sufficient supporting evidence in order to deviate from the default language. This ought to encompass more than ‘the domain name is in English, so…’ as otherwise the Rule would have been that ‘the dispute shall proceed in the language of the domain name’. Moreover, the Complainant’s argument and evidence should be strong enough to overcome the default position that fundamental fairness dictates that the Respondent be entitled to defend him or herself in his or own language, and despite this being inconvenient for some Complainants, it is of paramount importance in any credible legal dispute resolution regime.

In this case the Panelist reminds us that fairness is of the utmost importance and that some panelists have too readily deviated from the requirement that the language of the dispute match the language of the registration agreement. In Virgin Enterprises Limited v. Giannis Karanikolas, Karanikolas Ioannis, WIPO Case No. D2017-2290 (virgin1045 .com), the registrar was based in Greece and the Respondent wrote to WIPO after defaulting, as follows:

“I do not understand what you mean. I do not understand english. What happened with the domain name? I think now you make something illegal. This Domain name is mine and anyone who wants this have to buy it at least. You steal my Rights & my money. For which reason? Please contact with me Greek Language.”

The Panel made no comment or finding on the Respondent’s plea, one way or the other and proceeded in English. Did the Panelist consider the merits of the case here, including prior related cases, in concluding that he should proceed in English? Did the language of the website, which was in Greek get taken into account? Was the Respondent’s default the determinative factor? Should the Panelist have expressly considered the language of proceedings issue? The appropriate language of a proceeding is indeed a tricky issue and Panelist Nicholas Smith is a good example of a Panelist who takes seriously the issue of the “fundamental fairness” of the proceeding being in a language that is intelligible to the Respondent.