Undefended AKU .COM Transferred Despite No Evidence of Targeting

This inactive high-value domain name is capable of a multitude of non-infringing uses and was never used to target the Complainant. How did it end up transferred?

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (Vol. 3.30), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with commentary from our Director, Nat Cohen; General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch and Editor, Ankur Raheja. We invite guest commenters to contact us.

‣ Undefended AKU .COM Transferred Despite No Evidence of Targeting (aku .com*with commentary)

‣ Moving Beyond the Impersonation Test (thejw .org *with commentary)

‣ “Bad Faith Use” and “Unclear” Bad Faith Registration (habank .com*with commentary)

‣ Factually Misleading Allegations Without Legal Basis, Lead to RDNH(healthyr .com*with commentary)

‣ Who Would Have Guessed that ROAD LAW was a Registered Trademark? (roadlaw .com)

—–

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

Undefended AKU .COM Transferred Despite No Evidence of Targeting

<aku .com>

Panelist: Mr. Nick J. Gardner

Brief Facts: The Italian Complainant manufactures and sells a range of outdoor footwear under the brand name AKU, since 1983 and has an online presence at <aku .it>. It operates three production plants in Europe and has an annual turnover of almost EUR 23 million. The Complainant owns various trademarks for the word AKU or which include the word AKU, the earliest Italian trademark was registered on November 2, 1993. The Chinese Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name not earlier than November 25, 2016, and there is no evidence that it has ever been used in any way. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name at some time after 2017 and relies on the doctrine of passive holding of a domain name corresponding to a well-known trademark.

The AKU international trademark has designated China as a territory since 2005. The Complainant has carried out business in China through appointed distributors since 2010. Its turnover in 2015 was approximately EUR 330,000 and in 2016 approximately EUR 134,000. Its products under the brand name AKU have been promoted on various Chinese-language websites. It has been exhibited under the brand name AKU at various Chinese exhibitions. Its footwear has won awards in China – for example one of its shoes won an “Outside Gear of the Year” award in China in 2015.

The Complainant alleges at the relevant time, a simple search on one of the publicly-accessible trademark databases such as the USPTO, or a search on Google would have immediately revealed to the Respondent that the term “aku” is and already was a registered and widely-used trademark of the Complainant. It also alleges that MX records are configured for the disputed Domain Name which means there is a strong likelihood of it being (or potentially being) used for phishing or other fraudulent activities. Lastly, the Complainant relies on the Respondent having provided inaccurate registrant information and effecting a “Russian dolls” arrangement obscuring the registrant’s identity. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The Panel considers that the Complainant has established it has a significant reputation in the AKU trademark in relation to outdoor footwear and that reputation subsists internationally. It has also filed evidence which establishes that it had a significant reputation in China prior to the acquisition of the disputed Domain Name by the Respondent. In those circumstances, the Panel considers that an inference can be drawn that the Respondent’s registration of the disputed Domain Name was made with knowledge of the Complainant’s reputation and with intent to take advantage of that reputation. The Panel thinks it likely, as the Complainant says, that had the Respondent carried out a simple Google search when it acquired the disputed Domain Name it would have identified the Complainant and its AKU trademark. The Panel concludes that the Complainant’s case is sufficient to have expected the Respondent to explain relevant facts if it contended it had a legitimate interest unrelated to the Complainant, and it has failed to do so.

Overall it does not generally matter that the Respondent has not as yet used the disputed Domain Name. However, “Passive holding” can itself amount to bad faith registration and use where the holding involves a domain name deliberately chosen because of its association with the Complainant. See: Telstra Corporation Limited v. Nuclear Marshmallows, WIPO Case No. D2000-0003. The above reasoning is sufficient for the Panel to conclude that the disputed Domain Name has been registered and is being used in bad faith. For completeness, the Panel also considered the other points raised by the Complainant as regards the “Russian Doll” situation and configured MX records. However, due to a lack of proper information, the Panel attaches no weight to either of them.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Modiano & Partners, Italy

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

Undefended AKU .COM Transferred Despite No Evidence of Targeting

This inactive high-value domain name is capable of a multitude of non-infringing uses and was never used to target the Complainant. How did it end up transferred?

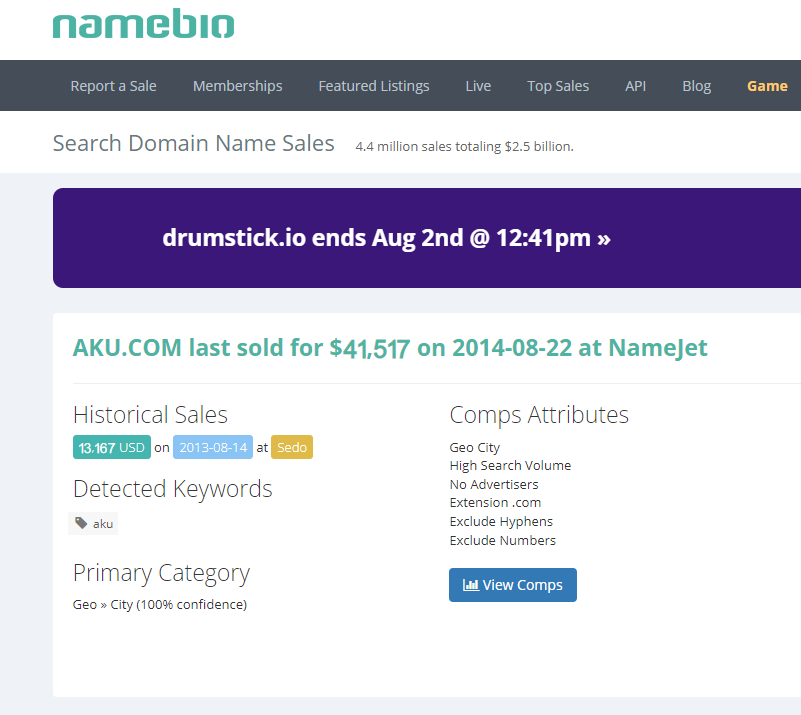

But first, congratulations are in order for my friend and colleague, Dr. Fabrizio Bedarida, who successfully represented the Complainant. His client, an Italian shoe company must be ecstatic about obtaining such a valuable three-letter .com domain name through the UDRP since it would otherwise have likely cost them hundreds of thousands of dollars to purchase it. Although online appraisal tools are notoriously unreliable, Estibot.com values this Domain Name at USD $144,000 and GoDaddy’s appraisal tool says that it is “too high to estimate”. DNJournal tracks secondary market domain name sales and shows that in 2023 three-letter .com domain names have commanded very high premiums on the secondary market, with for example, ECL .com fetching USD $600,000 (March 29, 2023), PFP .com fetching USD $353,000 (March 1, 2023), TXT .com fetching USD $300,000 (February 1, 2023, and most recently, HDL .com fetching USD $260,000. More useful data on three-letter .com sales is available at Embrace.com. The disputed Domain Name was in fact purchased and sold on August 22, 2014 for USD $41,517 according to secondary market sales tracked by NameBio.

According to the decision in this matter, the Domain Name was “likely acquired in late 2016”, over six years ago. That means that it likely changed hands since it was purchased in 2014 for $41,517 and accordingly, the Respondent in this case likely purchased it for more than that amount, which is a particularly handsome sum to pay for a “cybersquatted” domain name. It is also a lot of money to pay to sit on the domain name for over 6 years without making any apparent solicitation to the targeting of the cybersquatting, namely the Italian shoe company Complainant. It is similarly a long length of time to have apparently not used the Domain Name in any way to capitalize on the Italian company’s goodwill, such as infringement or passing off. Nevertheless, the Panel was able to determine that despite such facts, the Respondent clearly was a cyberquatter who targeted the Complainant.

From the decision, we can see that the Complainant’s counsel conducted historical Whois research, provided evidence of trademark rights, and presented evidence of sales volumes and reputation in order to demonstrate that it was the victim of cybersquatting. That however is not always sufficient when it comes to three-letter .com domain names, as the Panelist noted inter alia, “short-letter expressions that have meanings other than those claimed by the complainant” may mean that no one company has exclusive rights to the term (See in this regard Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena S.p.A v. Charles Kirkpatrick, WIPO Case No. D2008-0260 concerning the domain name <mps.mobi>. Indeed, as noted by the Panelist; It is also the case that registration of a short acronym can itself establish a legitimate interest where the registration is effected for its so-called inherent value – as opposed to its value because of its likely association with a particular trademark holder”.

Transfers of three-letter .com domain names are indeed difficult to obtain and exceptional. As ICA Director Nat Cohen noted in his CircleID article (October 26, 2022), of the 80 disputes on three-letter .com domain names since January 1, 2012 where cybersquatting was alleged, 77 were denied and RDNH was found 20 times. Nat Cohen also notes that of the three transfer decisions, two (namely, ado[.]com and imi[.]com – which was inadvertently not defended at the UDRP level) were challenged in court and overturned at the cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars, and one (ehf[.]com) was still pending in court.

Given the difficulty in using the UDRP to obtain a three-letter .com, the best hope that a Complainant generally has, is that the case isn’t defended and that it draws a particularly helpful Panelist. The odds are not good that a valuable three-letter .com domain name will go undefended, but the odds are great that a helpful Panelist will be drawn. At WIPO for example, the roster is generally limited to Panelists who act exclusively for trademark owners with none that regularly represent domain name registrants or act for both parties. Moreover, in this case the Complainant had the advantage of being represented by a WIPO Panelist. Fortunately WIPO did not appoint a Panelist who had previously served on a Panel with the Complainant’s counsel, and thereby attempted to avoid the appearance of bias.

Nevertheless, the Complainant got lucky, for there was no Response. It drew one of the most experienced and respected WIPO Panelists, Nick Gardner, who has acted for many “well known names [such] as Amstrad, British Gas, BSkyB, the FIA, Harrods, IBM, Intel, the Motion Picture Association, Nokia, and Unilever”. In previous issues of the Digest we noted and commented favorably upon Mr. Gardner’s excellent work as a presiding panelist in:

The zydus .com case; and

The colombiancoffee .com case.And we also covered favorably several cases where he was a co-panelist:

The gaggle .com case;

The dagi .com case; and

The kosmos .com case.It is with Mr. Gardner’s excellent past record as a Panelist in mind that it is so surprising that he came to such a questionable decision in this particular case, even with the expert representation provided by the Complainant’s counsel who undoubtedly did his utmost to provide robust evidence supporting his client’s allegations.

The Panelist stated:

“the Panel considers that the Complainant has established it has a significant reputation in the AKU trademark in relation to outdoor footwear and that reputation subsists internationally. It has also filed evidence which establishes that it had a significant reputation in China prior to the date the Disputed Domain Name was acquired by the Respondent. In those circumstances the Panel considers that an inference can be drawn that the Respondent’s registration of the Disputed Domain Name was made with knowledge of the Complainant’s reputation and with intent to take advantage of that reputation.”

Given the evidence of very modest sales and some tradeshow exhibitions etc, I can charitably accept the Panelist’s conclusion that the Complainant had a “significant reputation in China prior to the date that the Domain Name was acquired by the Respondent”. But a “significant” reputation isn’t a “major” reputation, as the Complainant doesn’t have a particularly well known, let alone famous mark, given paltry sales and relatively minimal exposure to the Chinese market at the material time. Indeed, the Panelist acknowledged that there are “some three letter trademarks where the evidence of fame and reputation is well established on a world-wide basis and it is generally straightforward to at least draw an inference that registration of a corresponding domain name will have been targeting that trademark holder” such as BMW, but this is not one of them.

Crucially, however, mere knowledge of a Complainant’s trademark does not equate to targeting of that Complainant, particularly when the Complainant’s trademark is not particularly well known and especially when it is not shown to be the sole or even predominant user of that mark. After all, if you were to register ABC .com, and there was an ABC cologne maker with a “significant” but not well known reputation, could it be inferred that it was the target of your registration, when there are many other ABC companies out there? Surely there would have to be some evidence that shows the targeting of this particular ABC company for such an inference to be reasonably drawn. The Panelist was specifically aware of this consideration when he stated;

It might also however conceivably have identified that there were other organisations which used the acronym “aku” . There is however no evidence to suggest that any other such organisation had any reputation in China, unlike the Complainant.”

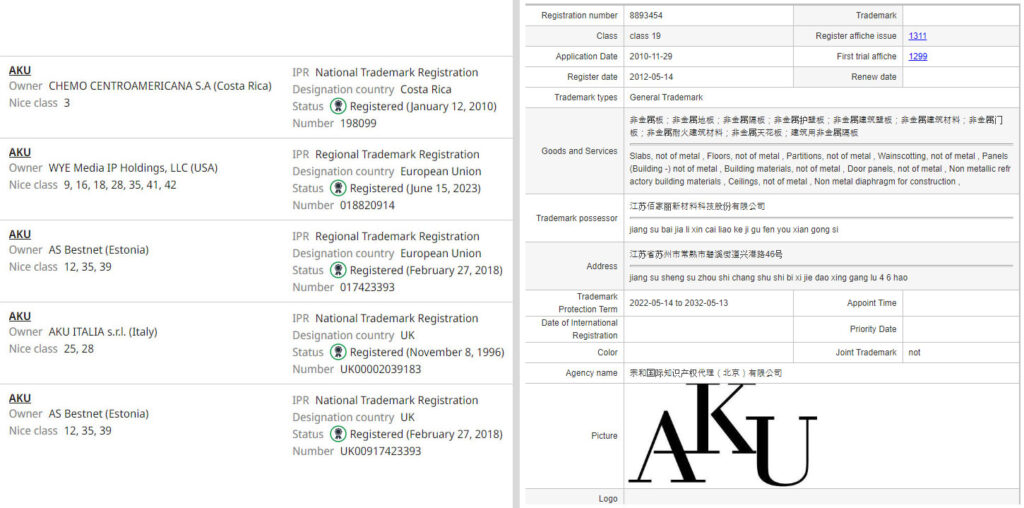

Now, if the Respondent had defended as it should have, the Respondent would likely have been able to show that there were numerous other trademark owners in China for AKU in connection with a variety of goods as there are throughout the world. But what obligation did the Complainant have in this regard? The Complainant must have been aware that there are numerous third party trademarks for AKU throughout the world that have nothing to do with the Complainant, including in China itself. Yet the Panelist concluded that “there is no evidence that any such organisation had any reputation in China” and puts the blame on the Respondent for not providing any such evidence. The Respondent is indeed responsible for its own defense, however the onus is on the Complainant to prove its case via evidence, and if its entire claim rests on it being the target then it is obliged to provide evidence that either; a) it is the exclusive or predominant user of the mark and therefore was the likely target; or b) there are no other companies that have a significant reputation in China or the world making it the likely target; or c) there was actual proof that it was the target, such as solicitations, infringement, passing off, targeted advertising, etc.

In the present case however, the Complainant apparently provided none of that evidence despite such evidence being well within its ability and control. For instance, the Complainant could have provided the Panel with a WIPO Global Brand Database and China trademark registry search showing that it was the only user of AKU, however such searches would have revealed numerous third party trademark owners other than the Complainant, including in China itself, such as the below examples:

The Complainant could have provided Baidu and Google searches from China from the material time or even currently, showing that it was the only company with any significant reputation in the world and in China in particular, making it the likely target, but it apparently did not nor likely could it have proven that its relatively modest reputation was far beyond any of the other third parties at the material time. The Complainant could have provided evidence that it was solicited by the Respondent or that the Respondent had a website targeting the Complainant, but it did not because the Respondent apparently never did.

Yet despite the Complainant apparently failing to provide any evidence of targeting whatsoever, the Panelist drew an “inference” that it was the target. When it comes to three-letter acronyms which any experienced Panelist would immediately realize are commonly used by numerous parties, one would have certainly expected the Panelist to demand evidence of targeting but unfortunately the Panelist just made a very helpful and totally unsupported “inference”. The Panelist appears to have sought comfort in his unsupported inference, because the Respondent did not defend, stating, “given the lack of Response that inference has not been rebutted”. However, given that there was no evidentiary basis to make such an inference since the Complainant failed to provide any evidence that it and not anyone else, was the likely target, there was no reasonable inference for the Respondent to rebut. Moreover, given that three-letter .com acronyms are known to be very valuable and that this one was owned by the Respondent for nearly six years, the absence of any evidence of solicitations or infringing use of it surely casts doubt on the Complainant’s weak and self-serving contentions.

Fundamentally, the error that the Panelist made here and which resulted in a windfall for the Complainant, was misapprehending the appropriate standard in no-response cases. By “inferring” without adequate evidence, that the Complainant was the target of the registration and then holding that inference “has not been rebutted”, the Panelist created what amounts to a “default judgment” which runs contrary to the Policy which demands sufficient evidence even in the absence of a Response. In other words, the Complainant’s case must stand on its own and not rely on the absence of a rebuttal for it to have efficacy. Here, an extraordinarily weak case for targeting only survived because the Panelist let it stand in the absence of a Response when he ought to have concluded that the Complainant simply failed to prove targeting.

The key consideration in undefended three-letter .com domain names where there is no evidence of targeting, was noted by Panelist Warwick Smith in Think Service, Inc. v. Juan Carlos aka Juan Carlos Linardi, WIPO Case No. D2005-1033 <hdi.com>. Panelist Smith stated that “there is no evidence of the Domain Name being in any degree distinctive” and crucially noted that:

“one can readily imagine that there would have been many individuals or corporations around the world (many of whom would not have had existing trademark or service mark rights), who would have been interested in acquiring such a domain name. That factor really makes it impossible for the Panel to conclude that the Respondent must have been aware of the Complainant’s mark, and acquired the Domain Name with the bad faith purpose of “extorting” money from the Complainant.” [emphasis added]

Remarkably, Panelist Gardner referenced the undefended pco .com case in his decision (PCO AG v. Register4Less Privacy Advocate, 3501256 Canada, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2017-1778), but apparently failed to follow its solid reasoning, only noting that in the PCO case the Complainant had failed to supply evidence that it was widely known by PCO. Panelist Adam Taylor in PCO .COM noted that “a number of UDRP cases relating to three-letter domain names reflect the fact that such terms are generally in widespread use as acronyms or otherwise and it is entirely conceivable that a respondent registered such a domain name for bona fide purposes”, and asked himself the critical question;

“So is there any evidence here which suggests that the Respondent registered the disputed domain name with the Complainant in mind?”

This is the question that Panelist Gardner apparently failed to ask himself, instead demanding of the Respondent that the Respondent rebut an “inference” that was bereft of supporting evidence.

In dismissing the Complaint, Panelist Taylor noted that like in the present case, “there is no evidence of any active website at the disputed domain name” and that the Complainant had “failed to establish passive holding in bad faith”, since the term PCO [like AKU], “is far from uniquely identified with the Complainant” and the Complainant overstated its case when it claims that there is no conceivable good faith use to which the disputed domain name could be put”. Panelist Taylor then rightly concluded;

“While the Panel takes account that, for whatever reason, the Respondent has not appeared in this proceeding to contest the Complainant’s allegations, this is outweighed by the fact that the disputed domain name is common three-letter acronym and there is no evidence whatever to link the Respondent’s selection of the disputed domain name with the Complainant. The Complainant’s key conclusions are unsupported and conclusory.”

Unlike Panelist Taylor’s proper application of the concept of “passive holding” as described above, Panelist Gardner unfortunately misapprehended the Telstra test. The Telstra test and the concept of “passive holding” specifically involves a highly distinctive and famous mark and requires that there be no “plausible actual or contemplated active use of the domain name by the Respondent that would not be illegitimate”. Here, it was obvious that not only was this mark not famous or distinctive, but there are potentially numerous possible legitimate uses of the Domain Name other than the Complainant given that its an acronym and nearly all, except for the most famous ones, are used by numerous third parties contemporaneously.

When UDRP decisions make unsupported transfers of valuable domain names, it is very likely that they will be overturned in court and I would not be surprised if that is the case here. The lesson to be learned from this case is that Panelists must maintain the onus on the Complainant to make its case via evidence and not rely on the absence of a Response to “rebut” an insufficient case. Secondarily, when it comes to obviously valuable domain names that are capable of being registered and used for a multitude of legitimate purposes, Panelists should be circumspect in ordering a transfer without firm and specific evidence of targeting. The aforenoted PCO .com and HDI .com cases should be foremost in mind when deciding undefended three-letter .com cases so as to avoid the injustice of transferring an inactive domain name capable of non-infringing use by a multitude of parties where there isn’t an iota of evidence of actual targeting.

Moving Beyond the Impersonation Test

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania v. Vincent Moore, WIPO Case No. D2023-2034

<thejw .org>

Panelist: Mr. Sebastian M.W. Hughes

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a non-profit corporation, which supports the worldwide religious, educational, and charitable activity of Jehovah’s Witnesses, which includes publishing Bibles, Bible-based publications, and other religious and educational materials. The Complainant has been using its JW trade mark since 1931 in connection with providing educational services and associated materials relating to the tenets of Jehovah’s Witnesses. The Complainant is the owner of trademark registrations in several jurisdictions worldwide, including the United States (registered on October 31, 2017). The Complainant has also registered and used the domain name <jw .org> since 1999 in respect of the Complainant’s website, which averages more than 2 million visitors per day. The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 5, 2020, and resolves to a website that contains content critical of the Complainant.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is not making any legitimate or fair use of the disputed Domain Name, as the disputed Domain Name illegitimately impersonates the Complainant for the purpose of misleading and diverting Internet users in search of the Complainant’s website and educational services and materials to the Respondent’s unrelated Website. The Complainant relies upon the decision in Netblocks Group v. Collin Anderson, WIPO Case No. D2020-2240, in contending that the use of the disputed Domain Name to impersonate the Complainant for the purpose of misleading and diverting Internet users “constitutes registration and use in bad faith, which cannot be cured by the content of the Respondent’s [W]ebsite”.

The Complainant further alleges that the disputed Domain Name itself does not in any way signal to potential visitors that the Website contains critical content. The Respondent contends that the Complainant in its teachings and theology views the definite article “the” as significant and that the Respondent has chosen to use the definite article “the” in the disputed Domain Name and on the Website in order to parody the Complainant’s teachings. The Respondent further contends that he has not registered and used the disputed Domain Name for commercial purposes, which the Website is not a commercial website, and it does not have a donation page.

Held: The central issue in this proceeding is whether the Respondent is able to establish, for the purposes of the Policy, that he is making a legitimate non-commercial or fair use of the disputed Domain Name. The Panel finds that even a general right to legitimate criticism does not necessarily extend to registering or using a domain name identical to a trademark, even where such a domain name is used in relation to genuine non-commercial free speech, panels tend to find that this creates an impermissible risk of user confusion through impersonation.

The Panel finds that the Respondent’s criticism of the Complainant on the Website is genuine and non-commercial, and not pretextual for cybersquatting, commercial activity or tarnishment. The disputed Domain Name is not identical to the trademark – it consists of the trademark prefaced by the word “the” – but neither does it consist of the trademark together with a derogatory term. Whilst the use of the definite article “the” in the disputed Domain Name and on the Website might be understood by a Jehovah’s Witness as parody, the Respondent’s evidence in this regard is not convincing, and certainly it is unlikely in any event that any such parody would be readily apparent to Internet users who are not Jehovah’s Witnesses. The decision relied upon by the Complainant is not directly on point, as it was a decision involving domain names identical to the complainant’s relevant trade mark.

In the present proceeding, the Panel finds that it would be readily apparent to Internet users (including Jehovah’s Witnesses) upon visiting the Website that it is not the Complainant’s website, but is rather a website critical of the Complainant. In all the circumstances, the Panel finds that a holistic approach assessing the totality of factors, in this case, supports the Respondent’s claim to a right or legitimate interest for the purposes of the second element of the Policy. In light of the Panel’s finding, it is not strictly necessary for the Panel to make any finding in respect of bad faith. The Panel nonetheless considers that the Respondent’s acknowledged use of the disputed Domain Name in respect of his criticism Website does not amount to bad faith registration and use for the purposes of the third element of the Policy.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Ruggiero McAllister & McMahon LLC, United States

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA Director, Nat Cohen:

Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.The reasoning in the decision on the criticism site, TheJW.org, points to a way forward that may resolve the long-standing schism between two conflicting views on the proper balance between trademark rights and free speech rights under the UDRP. Panelist Sebastian Hughes relied on the “totality of circumstances” or “holistic approach” proposed by Panelist Georges Nahitchevansky in the MomsDemand.org decision (“Everytown for Gun Safety Action Fund, Inc. v. Contact Privacy Inc. Customer 1249561463 / Steve Coffman, WIPO Case No. D2022-0473). Nahitchevansky proposes a multi-pronged analysis that factors whether the content of the website is legitimate, non-commercial criticism. Zak Muscovitch, in his comment on the MomsDemand.org decision, described it as a “significant contribution to the case law” (see here).

As more fully discussed in WIPO Overview 2.0, Section 2.4, UDRP jurisprudence on criticism sites has long been subject to a schism between two conflicting approaches – a View 1, that a critic may not “impersonate” the Complainant’s trademark by using an exact match domain name regardless of the legitimacy of the non-commercial criticism, and a View 2, that legitimate non-commercial criticism establishes a legitimate interest regardless of the domain name.

Version 3.0 of the WIPO Overview at Section 2.6.2 attempted to elevate View 1 to the prevailing view with View 2 a possible exception to the general approach for parties that were exclusively located in the U.S. (WIPO Overview, Section 2.6). Yet as Igor Motsnyi notes in his comment on tibtecag .com (see comment here), this is at best a “seeming consensus” in favor of View 1, such that the WIPO Overview 3.0, which dates back to 2017, may have been premature in assessing a lack of continuing strong support for View 2, or variations thereof.

One problem with View 1 is that it conflicts with the Policy. This is compellingly articulated by David Bernstein in his dissent in <dellorusso.info>, Joseph Dello Russo M.D. v. Michelle Guillaumin, WIPO Case No. D2006-1627 (emphasis added):

The alternative view, which has been adopted by the majority here, is not supported by the Policy or by United States trademark law. As the majority notes, paragraph 4(c)(iii) provides as an example of how to demonstrate rights or legitimate interests in a domain name that the registrant is “making a legitimate noncommercial or fair use of the domain name, without intent for commercial gain to misleadingly divert consumers or to tarnish the trademark or service mark at issue.” It may be correct, as the majority notes, that use of <dellorusso.info> might misleadingly divert consumers to Respondent’s website, but it is undisputed that Respondent has exhibited no “intent for commercial gain” through her website. In these circumstances, even if a <trademark.TLD> domain name might initially divert consumers, and even if that diversion might be misleading because the domain name does not, on its own, communicate that the website is not operated by the trademark owner, the exception of paragraph 4(c)(iii) cannot apply because there is no intent for commercial gain, and that phrase is a critical component of paragraph 4(c)(iii).

Bernstein accurately reads the Policy here. When there is no “intent for commercial gain” and the registrant is “making a legitimate noncommercial” use of the domain name, the registrant is not violating the Policy. There are no exceptions to this, not even for an exact match “impersonating” domain name.

He further elaborated on these views in <SermoSucks .com>, (Sermo, Inc. v. CatalystMD, LLC, WIPO Case No. D2008-0647), where he recognized that the UDRP may inevitably be in conflict with some national laws if either View 1 or View 2 is universally adopted, as some national laws do not permit a criticism site to “impersonate” a mark, while some do, with the United States being the most prominent example. He therefore argued that panelists ought to be guided by the national laws applicable the parties by considering “the principles of law that it deems applicable”, as provided for in Paragraph 15(a) of the Rules, such that the UDRP may gain in predictability what it loses in consistent application of either View 1 or View 2.

This Panel rejects the notion that the choice here is between consistency and “chaos”. 1066 Housing Association Ltd. v. Mr. D. Morgan, WIPO Case No. D2007-1461. Either way, an inconsistency will be introduced into the application of the Policy. If, for example, all Panels “interpret[ed] the Policy in as uniform a manner as possible regardless of the location of the parties”, id., and consistently applied “view 1” of the Decision Overview, the result, at least in the U.S., would likely be a string of legal challenges by losing Respondents under paragraph 4(k) of the Rules. Based on the U.S. precedents listed above, the expected result would be that the courts would find that the domain name does not violate the Lanham Act and the courts would refuse to uphold the transfers ordered by the UDRP Panels. Similarly, if all panels consistently applied view 2 regardless of the location of the parties, one would expect trademark owners in non-U.S. jurisdictions to challenge the domain names in court rather than through the UDRP, where they would obtain transfer orders that would be inconsistent with the legal principals underlying view 2 of the Decision Overview. Thus, either way, UDRP decisions would be inconsistent with the expected results in some countries’ courts…

It is thus common for panels to consider the relevant national laws in assessing whether Complainant has established trademark rights; there is no reason why panels cannot also consider national laws in assessing whether Respondent has established a fair use right.As he goes on to say, to adopt View 1 could place the UDRP in conflict with the Lanham Act, the Anti Cybersquatting Protection Act (ACPA), and perhaps even in conflict with constitutionally protected free speech rights. Under the ACPA, there is no carve out for “impersonating domain names” to the legitimacy of offering genuine, non-commercial, criticism:

(ii) Bad faith intent described under subparagraph (A) shall not be found in any case in which the court determines that the person believed and had reasonable grounds to believe that the use of the domain name was a fair use or otherwise lawful.

(https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/15/1125)View 1 also conflicts with the original goals and limitations of the UDRP. The Final Report of the First WIPO Internet Domain Name Process April 30, 1999 (see here), in paragraph 34 states (emphasis added):

34. It is further recognized that the goal of this WIPO Process is not to create new rights of intellectual property, nor to accord greater protection to intellectual property in cyberspace than that which exists elsewhere. Rather, the goal is to give proper and adequate expression to the existing, multilaterally agreed standards of intellectual property protection in the context of the new, multijurisdictional and vitally important medium of the Internet and the DNS that is responsible for directing traffic on the Internet 25. The WIPO Process seeks to find procedures that will avoid the unwitting diminution or frustration of agreed policies and rules for intellectual property protection.

Adopting View 1 as the consensus approach frustrates WIPO’s stated goals for the UDRP. Especially for parties based in the U.S., View 1 DOES create new rights of intellectual property, and DOES accord greater protection for intellectual property that is found in the U.S. legal code. Further View 1 DOES NOT give proper expression to the multilaterally agreed standards of intellectual property, as the U.S. legal system is in direct conflict with View 1.

In the DoverDownsNews .com case from 2019, David Bernstein retreats from his earlier support of View 2 and casts his lot with View 1 in the interests of promoting a consistent approach to the issue that is not fragmented based on the countries to which the parties belong and which also does not require panelists to interpret national laws that they may not be familiar with. Bernstein offers an in-depth discussion of the issues which is worth reading in full.

Yet if the goal is adopting a clear, consistent approach across the UDRP, View 2 has a much stronger claim than View 1 as the choice for the consensus approach. Of the two, only View 2 is consistent with the language of the Policy. Of the two, only View 2 is consistent with WIPO’s goals stated in the Final Report not to create new intellectual property rights and not to accord greater protection for intellectual property than would exist otherwise. The Final Report justifies the adoption of the UDRP as a distillation of multilateral agreed standards for intellectual property. When there is no such multilateral agreement on an issue, such as the legitimacy of using an impersonating domain name for non-commercial criticism, this argues for a more limited scope to the rights granted under the UDRP rather than a more expansive scope. View 1 grants trademark holders more expansive rights than View 2. In the absence of multilateral agreement on those rights, View 2 should prevail.

If the goal is to have a consistent approach and the options are View 1 or View 2, then who will be disadvantaged and to what extent will depend on which view is adopted as the consensus approach.

If View 1 is chosen, individual critics will be disadvantaged, their lawful right to free expression will be suppressed, and the remedy of filing in court will likely be beyond their means.

If View 2 is chosen, some visitors looking for a brand owner may experience a few seconds of confusion, and the brand owner will likely have ample means to pursue a legal action in the relevant national court if they believe they have been harmed to that great an extent.

Those who favor View 1 over View 2 value avoiding a momentary confusion on the part of a company’s customers over the free speech rights of individuals.

The most troubling argument that the Panelist advances in DoverDownsNews .com in favor of adopting View 1 as the consensus approach is the following (emphasis added):

Because these facts are more difficult to assess in the context of the UDRP, which provides expedited proceedings with no opportunity for discovery or cross-examination, there are rational policy reasons for using the impersonation test – which is relatively easy to apply – and leaving these more difficult factual disputes to a court should parties from the United States wish a more robust assessment of their rights under the Lanham Act and under the First Amendment. For example, if Respondent takes issue with the Panel’s decision (which, to be clear, is applying the UDRP, not United States trademark law), Respondent remains free to seek judicial review by filing an action in a state or federal court in the location of mutual jurisdiction (here, Fort Davis, Texas, which is within the jurisdiction of the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas) within ten business days of the Panel’s decision in order to prevent transfer. In any such action, Respondent would be free to argue that his conduct, while possibly violative of the UDRP’s impersonation test, is nevertheless permitted under the Lanham Act because the initial interest confusion here does not violate the Lanham Act, or that his conduct is protected speech under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. The court would thereafter have the opportunity to weigh all the likelihood of confusion factors in considering how to treat the initial interest confusion in this case, and could balance Respondent’s potential First Amendment interests against Complainant’s concerns that Respondent’s conduct is causing confusion of consumers. Both parties would be afforded the opportunity to engage in discovery and to confront witnesses—procedural mechanisms unavailable in UDRP proceedings.

While the Panelist acknowledges that the adoption of View 1 may violate the legal rights, and perhaps even the Constitutional rights, of some respondents, unfortunately the remedy proposed to cure this violation is impractical. It is not realistic to expect that an individual who is critical of a large corporation will voluntarily enter into a hugely expensive Federal Court battle with a corporation merely for the purpose of using an exact match domain name for a criticism site. The practical consequence of the consensus adoption of View 1 would be the successful, unlawful, suppression of the free speech rights of many respondents, particular in the United States, for the benefit of brand owners who do not like their brands being incorporated into domain names used for criticism sites.

View 1 as a consensus unjustifiably limits the free speech rights of registrants who are unlikely to have practical recourse available, thereby unbalancing the UDRP in a damaging manner.

“Bad Faith Use” and “Unclear” Bad Faith Registration

Webster Financial Corporation v. Rune Straus, NAF Claim Number: FA2305002046207

<habank .com>

Panelist: Ms. Francine Tan

Brief Facts: The Complainant is one of the largest administrators of health savings accounts in the U.S. and holds approximately USD $22 billion in assets. It provides business and consumer banking, mortgage, investment, trust, insurance and other financial services and has an online presence at <hsabank .com>. The Complainant has rights in the HSA BANK mark through its registration of the mark with the USPTO (earliest registered on October 24, 2006). The Complainant has since at least as early as December 10, 2003, through its licensee Webster Bank, National Association, exclusively, continuously and on a widespread basis used and promoted the HSA BANK mark in commerce. The disputed Domain Name was registered on October 9, 2005.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent’s website brings Internet users to a website containing links to the Complainant’s competitors which offer services in direct competition with those offered by the Complainant and that the Respondent engages in typosquatting. The Respondent contends that he acquired the disputed Domain Name 18 years ago and if a domain name was registered in good faith, it cannot, by changed circumstances, the passage of years, or intervening events, later be deemed to have been registered in bad faith. The Respondent further contends that he has been living in China and had no knowledge of the Complainant’s business and is using the disputed Domain Name to generate advertisement links for all banks, and not just HSA banks. Acquiring domain names to trade them for profit or to exploit them for pay-per-click revenue is not, in itself, objectionable in the absence of any targeting of the Complainant.

Held: Pursuant to Section 2.9 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, “panels have found that the use of a Domain Name to host a parked page comprising PPC links does not represent a bona fide offering where such links compete with or capitalize on the reputation and goodwill of the complainant’s mark or otherwise mislead Internet users”. In this case, the PPC links are related to the Complainant’s trade mark, albeit there is an omission of the letter “s”, and generate search results with competing goods/services to those offered by the Complainant. In the Panel’s view, such use does not confer rights or legitimate interests to the Respondent.

The specific combination of the disputed Domain Name which contains the term “bank” and features letters which are confusingly similar to the letters “HSA” in the Complainant’s trade mark is strongly indicative of bad faith as well. The Complainant had common law rights in the HSA BANK trade mark since December 10, 2003, which is a date preceding the Respondent’s registration of the disputed Domain Name. The Panel also notes that the evidence in the case file shows that the disputed Domain Name was being offered for sale.

The fact that the disputed Domain Name resolves to a webpage that contains links to the Complainant’s competitors shows, in the Panel’s view, that the Respondent has intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to the site, and to trade off the reputation of the Complainant’s trade mark, in this case through typo-squatting. The offering of links to competitor websites is a disruption to the business of the Complainant’s business and evidence of bad faith registration and use.

While it may be unclear why the disputed Domain Name was initially registered, and even if the Respondent were a domainer (which has not been established by the Respondent), the Panel considers these points irrelevant where the domain name is subsequently used to attract Internet users by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s mark, and bad faith can be inferred.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Gail Podolsky of Carlton Fields, P.A., Georgia, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: We had the honour of Panelist Francine Tan, who is a former INTA Director, participate in the first ever UDRP Moot Hearing which the ICA held in conjunction with INTA. If you haven’t seen it yet, you must see it! Counsel were Georges Nahitchevansky (Complainant) and Karen Bernstein (Respondent). Panelists were Steve Levy, Gerald Levine, and Francine Tan.

Unfortunately, my time this week has been taken up by the above AKU .com case, so my comments here will be very brief. Two things stand out to me; 1) If it was unclear why the domain name had been initially registered, can there be registration and use in bad faith, as is required by the Policy?; and 2) Could it be that the PPC links did not target the Complainant but rather showed competitors to the Complainant just because the word “bank” was in the Domain Name?

Lastly, note that the Complainant previously lost two related cases:

hssbank.com NAF 1705353 2017-01-06 Claim Denied hsbank.com NAF 1704955 2017-01-03 Claim Denied

Factually Misleading Allegations Without Legal Basis, Lead to RDNH

Healthyr, LLC v. Jonathan Curd, WIPO Case No. D2023-1802

<healthyr .com>

Panelist: Mr. Lawrence K. Nodine

Brief Facts: The Complainant is an online health provider, specifically offering at-home tests, telehealth services, and pharmacy services. The Complainant use the Domain Name <behealthyr .com> (registered on April 20, 2022) and uses the corresponding website to offer its services in the United States. Additionally, the Complainant has a pending US trademark for the mark HEALTHYR (filed on September 29, 2022) that claims a first use date of September 21, 2022. The Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name on August 24, 2006, and it currently resolves to a pay-per-click (“PPC”) webpage featuring links for “medical products”, “food supplement”, and “nutritional supplements”. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name while the Complainant was preparing to launch its business, and shortly before the Complainant filed its application for registration with the USPTO.

The Complainant also attempted to purchase the disputed Domain Name from the Respondent through a GoDaddy broker on or around September 21, 2022. The Respondent refused Complainant’s final USD $5,000 offer and counteroffered USD $7,500, which the Complainant did not accept. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent intends to ransom the disputed Domain Name to the highest bidder, which does not constitute legitimate, non-commercial fair use. The Respondent contends that it has rights and legitimate interest in the disputed Domain Name because the disputed Domain Name is a phonetic equivalent of the generic word “healthier”, and the Respondent has used the disputed Domain Name in relation to its generic meaning for monetization in connection with health-related topics. The Respondent further contends that it registered the disputed Domain Name seventeen years ago in 2006, long before the Complainant claims to have first used the HEALTHYR mark.

Held: UDRP panels have recognized that the use of a domain name to host a page comprising PPC links would be permissible and therefore consistent with respondent rights or legitimate interests under the UDRP – where the domain name consists of an actual dictionary word(s) or phrase and is used to host PPC links genuinely related to the dictionary meaning of the word(s) or phrase comprising the domain name, and not to trade off the complainant’s (or its competitor’s) trademark (see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.9). In this sense, the Panel notes that the disputed Domain Name is the phonetic equivalent of the dictionary term “healthier” and that the Respondent has used the disputed Domain Name to host PPC links related to health.

The Complainant has failed to prove registration in bad faith. The record shows that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name in August 2006, seventeen years before the Complainant first used the HEALTHYR mark. Therefore, the Respondent could not have registered the disputed Domain Name to profit from the Complainant’s mark or to interfere with the Complainant’s business. Further, the record shows Respondent’s final offer for the disputed Domain Name was USD $7,500. While this likely exceeds the price, the Respondent paid to purchase the disputed Domain Name, there is no per se rule that an asking price over out-of-pocket costs constitutes definitive evidence of bad faith use of a domain name. “If the Respondent’s interest in the disputed Domain Name is legitimate he is entitled to seek whatever price he wishes.” [see Reindl Gesellschaft m.b.H. v. Stanley Pace, WIPO Case No. D2019-0160].

RDNH: The Panel finds Reverse Domain Name Hijacking because the Complainant made factually misleading allegations and key arguments that lacked a plausible legal basis. The Complainant had no basis for its critical allegation that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name while the Complainant was preparing to launch its business… and therefore registered the Domain Name for the sole purpose of extracting a large sum of money from the Complainant. The Complainant knew that this was incorrect. In fact, the Complainant expressly alleged that the disputed Domain Name “was created 7/25/05”. Further, it was misleading for the Complainant to affirmatively rely on later records, but omit the earlier records, or to at least acknowledge their content, when basing arguments on the evolution of the negotiations, especially given that these negotiations form the foundation of the Complainant’s allegations of bad faith.

Based on the record evidence, the Complainant was well aware of the Respondent’s ownership of and use of the disputed Domain Name on the same date it first used the HEALTHYR mark in United States commerce and before the Complainant filed its trademark application for the same. In light of the above, the Panel finds that the Complainant brought the Complaint in bad faith, within the meaning of Rule 15(e), in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Burr & Forman LLP, United States

Respondents’ Counsel: John Berryhill, Ph.d., Esq., United States

Comment by Newsletter Editor Ankur Raheja: This is a well-reasoned decision by Panelist Lawrence K. Nodine, that upholds the Respondent’s legitimate interest in the Domain Name which was used for health-related PPC links related to the meaning of the Domain Name’s phonetic equivalent, in terms of the WIPO Overview 3.0, section 2.9. The said position has been upheld in numerous previous decisions; see for example TranScrip Partners LLP, TranScrip Limited v. Abstract Holdings International Ltd, Domain Admin, WIPO Case No. D2021-2220:

Here, “transcrip” is an obvious reference to “transcript” and the PPC links refer to transcribing activities and transcriptions. They do not refer to or target the pharma and biotech industries in which Complainant operates as a service provider.

Respondent’s business model of “registering generic, descriptive, misspelling of common words, and acronym domain names” has been held to be a legitimate endeavor, so long as targeting of another’s trademark is not found. Monetizing domain names because of and in relation to their dictionary value is not in itself illegitimate, so long as there is no targeting of trademarks.

However, the Panel in the UDRP matter of <habank .com> (reported above) took quite a contrasting approach, wherein as well the resolving webpage displayed links in relation to banking, based upon the keyword ‘bank’ incorporated in the disputed Domain Name.

Further, in the present matter, the disputed Domain Name <healthyr .com> was registered seventeen years before the Complainant first used the HEALTHYR mark. Therefore, given the conjunctive requirement of the Policy, the Complainant could never prove registration in bad faith. See South32 Limited v. South32, South32 is a trademarked film company, WIPO Case No. D2023-1808: “Given the conjunctive requirement of proving both registration and use in bad faith, the Complaint must fail and the question of use in bad faith is moot.” Also, there is nothing wrong in entering negotiations for the Domain Name when approached by the Complainant, as it is not a breach of the Policy unless Domain Name was acquired “primarily for the purpose of selling, renting, or otherwise transferring the domain name registration to the complainant… ” or if otherwise, the Respondent has legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name [see Reindl Gesellschaft m.b.H. v. Stanley Pace, WIPO Case No. D2019-0160]. In short, there was no ground on which Bad Faith could be held against the Domain Name registrant.

Additionally, the Panel upheld this as a matter of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking (RDNH), given that the “Complainant made factually misleading allegations and key arguments that lacked a plausible legal basis”. The Panel relied upon the reasons articulated by panels for finding RDNH under WIPO Overview 3.0, section 4.16: (iv) “the provision of false evidence, or otherwise attempting to mislead the panel”; and (v) “the provision of intentionally incomplete material evidence–often clarified by the respondent”. Indeed, firstly the Complainant was well aware of the Domain Name creation date and secondly, the Complainant omitted the earlier records, when basing arguments on the evolution of the negotiations. Otherwise as well, given the undertakings in paragraphs 3(b)(xiii) and (xiv) of the UDRP Rules, UDRP Panels have held that a represented complainant should be held to a higher standard [WIPO Overview 3.0, section 4.16]. See for example Voys B.V. v. Thomas Zou [WIPO Case No. D2017-2136]: and in Majid Al Futtaim Properties v. Domain-It!, Inc. [WIPO Case No. D2021-0591].

Who Would Have Guessed that ROAD LAW was a Registered Trademark?

Truckers Choice Services, Inc. v. Brad Klepper, Drivers Legal Plan, Ltd., WIPO Case No. D2023-1117

<roadlaw .com>

Panelists: Mr. Evan D. Brown, Mr. W. Scott Blackmer and Mr. Brian J. Winterfeldt

Brief Facts: The Complainant is in the business of providing legal services to commercial truck drivers accused of violating traffic laws. It owns the trademark ROAD LAW registered with the USPTO (April 11, 2000). The Complainant asserts that it has used the ROAD LAW mark in commerce since at least as early as June 1, 1998. The disputed Domain Name was registered on September 11, 2002, by the Respondent law firm “dedicated to protecting the rights of truck drivers, and therefore the interests of trucking companies”. The disputed Domain Name redirects Internet users to the Respondent’s website found at <driverslegalplan .com>. The Respondent contends that it registered and used the disputed Domain Name because of its highly descriptive properties and that it did not target the Complainant, shown by the fact that the Respondent registered and used other domain names purportedly descriptive of the services that the Respondent provides. The Respondent asks the Panel to find that the Complainant engaged in Reverse Domain Name Hijacking and that the Panel also consider the equitable doctrine of laches.

The Complainant asserts that the “Respondent’s bad faith registration and use of the disputed Domain Name is further evidenced by the fact that Respondent was fully aware Complainant operates under the name, ROAD LAW because Complainant’s founders were employed by an entity which was affiliated with the Respondent before they left to create Truckers Choice Services, LLC in 1998. Truckers Choice Services, LLC merged to Truckers Choice Services, Inc. in 2000. The owners of the affiliated entity were aware of the Complainant’s company when they left and had adequate knowledge of the ROAD LAW mark as early as the late 1990s.” The Panel issued an Administrative Panel Procedural Order, inviting the Complainant to submit evidence and any additional argument concerning the above assertions in the Complaint. The Procedural Order also stated that the Panel would be interested in seeing evidence that corroborates the assertions that “Respondent was fully aware Complainant operates under the name, ROAD LAW” as asserted in the Complaint.

Held: The Complainant has provided evidence apparently uncontroverted of its longstanding use and registration of the ROAD LAW trademark. Even if the Panel were to find that the ROAD LAW mark is descriptive, the more than 20 years of use, and the registration of the mark, would have caused the mark to have acquired distinctiveness in the marketplace. Despite the Respondent’s claims of deriving value from the use of the disputed Domain Name, any rights arising from such use do not alter let alone prevail over the rights that the Complainant has in the ROAD LAW mark due to the Complainant’s over 20 years of consistent and uninterrupted use. The Respondent further argues that laches should guide the Panel in denying the Complaint. The Panel reiterates that the UDRP does not contain a specific limitation period, and there is a consensus view that delay in bringing a complaint does not of itself prevent a Complainant from filing under the UDRP, nor from potentially succeeding on the merits. Hence, the Panel rejects the Respondent’s laches arguments.

The Complainant asserts that the Respondent knew about the Complainant and its ROAD LAW mark and provides assertions in support. Many of the assertions relating to the Respondent’s knowledge of the disputed Domain Name are from 20 years or more ago. Accordingly, it is not unreasonable to conclude that the Respondent may have no specific recollection of knowledge of the ROAD LAW mark from that time period in the past. Nonetheless, the Panel finds it more likely than not that the Respondent was aware of the Complainant and its ROAD LAW mark when it registered the disputed Domain Name in 2002. Given the various connections between the Parties, it is hard to explain the Respondent’s decision to register the disputed Domain Name as not in relation to the Complainant and its rights. The Panel finds this to be bad faith registration.

The Respondent further admits that it is using the disputed Domain Name for commercial purposes. The Panel finds this use of the disputed Domain Name which is identical to the Complainant’s mark registered more than 20 years ago and has been used extensively in commerce to be a bad faith effort to seek to trade on the Complainant’s trademark rights. This is bad faith use of the disputed Domain Name.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Dunlap Codding, P.C., United States

Respondents’ Counsel: McAfee & Taft, United States