No RDNH Finding Leads to Questions About Treatment of Complainants Versus Respondents:

As noted by Andrew Allemann in an article in Domain Name Wire this past week, the primary allegations in the Complaint were unsubstantiated and the Complaint was essentially dead on arrival. Under the circumstances, the lack of an RDNH finding in the <gpi .com> decision is surprising.

It led me to think about the respective standards of conduct expected from respondents and from complainants under the UDRP and the inferences as to bad faith intent from a failure to comply with such standards. Read further commentary

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.8), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ No RDNH Finding Leads to Questions About Treatment of Complainants Versus Respondents (gpi .com *with commentary)

‣ Respondent fails “Oki Data” test but prevails on bad faith (airstreammarketplace .com *with commentary)

‣ Uninterrupted Chain of Ownership Precedes Complainant’s Trademark (ziip .com *with commentary)

‣ Panelist Dismisses, But Leaves Door Open for Refiled Complaint (silverpointequity .com *with commentary)

‣ Respondent Attempts to Pass Off as Complainant (stormtechshop .com)

—-

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

Follow this personal ICA series on domain investing by brandable domain investor and acquisition broker Sten Lillieström, and take the opportunity to gaze into the microcosm of domain investing.

The Brandable Idea

The Brandable Idea

– Mr. Sten Lillieström

In the previous article we examined the laws of tradition as they pertain to domain investing. According to the The legacy idea, datapoints such as search keyword metrics allegedly reveal if a domain name is valuable or not. At the same time, end user preferences indicate that there is more to the story. continue reading. continue reading

No RDNH Finding Leads to Questions About Treatment of Complainants Versus Respondents

Great Plains Ventures, Inc. v. CARQUEST, NAF Claim Number: FA2312002076391

<gpi .com>

Panelist: Ms. Nathalie Dreyfus

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1968, is the parent company of Great Plains Industries, Inc. It is respected globally for its high-quality fuel transfer pumps, fuel meters, flowmeters, and industrial instrumentation for fluid transfer pumps and liquid flowmeters. These products are offered under Great Plains’ GPI®, FLOMEC®, and GPRO® brands and serve industrial, commercial, and retail customers in various industries. The Complainant first began offering its products in commerce under the GPI brand at least as early as 1972. On May 13, 1976, it filed an application with the USPTO for the stylized GPI trademark, and on June 5, 1985, applied for the GPI word mark. It claims to have devoted extensive resources to advertising and marketing expenditures for its GPI brand of products. The Respondent is the parent of a large group of subsidiaries, which includes but is not limited to General Parts International, Inc. and its subsidiaries, including General Parts, Inc. The disputed Domain Name at issue <gpi .com> has been registered by Advance and its predecessors for over twenty years – initially registered by General Parts, Inc. long before its 2014 acquisition by the Respondent.

General Parts, Inc. first commenced using the name and trademark GPI at least as early as March 16, 1972. It obtained a US trademark registration for a GPI & Design mark on September 24, 1974, and renewed that GPI Registration multiple times, however, the trademark lapsed in 2014. The Respondent uses the subdomain <openwebs .gpi .com> to administer an e-commerce website for its B2B customers and also uses various other subdomains for external and internal uses. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent’s bad faith in registering the disputed Domain Name should be determined as of 2010 because the transfer of a domain name to a third party amounts to a new registration and that successive renewals of a domain name constitute re-registration. Therefore, the Respondent had actual and constructive notice of Complainant’s prior rights in the GPI mark at the time it registered the Domain Name.

Held: The Respondent has used the disputed Domain Name in connection with its business, the automotive aftermarket, which is different from the Complainant’s, an industry for fluid transfer pumps and liquid flowmeters. Moreover, the Complainant put forward no evidence demonstrating the Respondent’s will to divert the Complainant’s consumers or to tarnish the Complainant’s trademarks. The Panel accepts that GPI is an acronym for General Parts, Inc., as well as General Parts International, Inc. Indeed, the Panel finds that when the Domain Name was registered, General Parts, Inc., had long used GPI as a name and a trademark. General Parts is still referred to as “GPI” on Advance’s website and in press releases, as well as Advance’s SEC filings, and in many third-party articles and other media. The Panel finds the Complainant has not established that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

However, whilst it is well established that the transfer of a domain name to a third party does amount to a new registration, it is also generally accepted that such is not the case where there is evidence to establish an unbroken chain of underlying ownership by a single person. There was no transfer to a new and unaffiliated registrant in 2010, and Advance Auto Parts, Inc. did not acquire the General Parts companies until 2014. The Panel finds that there has been no break in the chain of possession of the disputed Domain Name. The Panel further agrees that the Complainant put forth no evidence that the Respondent had actual and constructive notice of Complainant’s prior rights in the GPI mark at the time it registered the Domain Name. If a domain name was registered in good faith, it cannot, by changed circumstances, the passage of years, or intervening events, later be deemed to have been registered in bad faith. The Panel finds that the Complainant has not satisfied its burden of showing bad faith registration. Besides, the disputed Domain Name is being used in good faith.

RDNH: The fact that the Complaint has failed is not sufficient in itself to support a finding of reverse domain name hijacking. The letters “GPI” have an obvious derivation from the General Parts, Inc., name. However, the Panel finds that the Complainant couldn’t ascertain if and how the Respondent was using the disputed Domain Name in the absence of a public-facing use such as a publicly accessible website. The fact that the use was not open to public inspection is a factor which must be taken into account in weighing the appropriateness under the Policy of the Complainant’s decision to bring the Complaint.

The Complainant owned incontestable Trademark registrations, the Respondent had no registration at the time of filing the Complaint, and the Respondent did not seem to be making any use of the GPI mark. Moreover, although the Panel understands that the Respondents’ offer to try to settle this dispute was a good-faith effort to avoid the expense and inconvenience of litigation, the Panel concludes that it did not bring the Complaint in bad faith.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Kelly Mulcahy of KRONENBERGER RESENFELD, LLP, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Jennifer Fairbairn Deal of Brient IP Law, LLC, USA

Case Comment by ICA Director and Domain Name Investor, Nat Cohen:

Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

As noted by Andrew Allemann in an article in Domain Name Wire this past week, the primary allegations in the Complaint were unsubstantiated and the Complaint was essentially dead on arrival. Under the circumstances, the lack of an RDNH finding in the <gpi .com> decision is surprising.

It led me to think about the respective standards of conduct expected from respondents and from complainants under the UDRP and the inferences as to bad faith intent from a failure to comply with such standards.

Some panelists hold that it is the responsibility of a prospective domain name registrant to search global databases of trademarks for marks that are similar to the domain name that she wishes to register and to avoid registering a domain name that is similar to any mark found therein. Fortunately, this approach has been widely discredited for it does not stand up to scrutiny. The essence of cybersquatting is that the registrant is aware of the mark holder prior to registering a domain name and registers the domain name in bad faith to target the mark holder’s goodwill. A domain name that is registered without awareness of the Complainant cannot be cybersquatting (though it remains up to the Panel to assess the veracity of the Respondent’s representation of lack of prior awareness, especially when the mark is globally famous).

Even a domain name registered for speculative resale with awareness of the Complainant is not necessarily cybersquatting. If a trademark search is conducted prior to the domain name being registered and a similar mark is found, that does not necessarily mean that the domain name is off limits for registration and for resale. Registration of a mark does not grant a global monopoly on all commercial uses. Especially if the mark is based on a dictionary-word or is otherwise non-distinctive, such that the term has widespread appeal independent of any trademarked use and is therefore inherently desirable and also in relatively short supply, a domain investor may have a legitimate interest in registering a similar domain name and offering it for general sale. Such a domain name may be a perfect fit for a start-up that is in a different area of commerce than the existing mark holder and that is just as entitled to utilize the domain name as the existing mark holder. I discuss this at greater length in an article in Westlaw (read here):

“Is it in the public interest for the new entrant to be able to purchase the exact match dot-com domain name if it is available for sale and if the new entrant so chooses? Or is it in the public interest for older trademark registrants to be able to hoard all the most desirable domain names and deny them to new entrants?”

This question of the standards of conduct comes into sharp focus as the Panelist in the <gpi .com> dispute imposes such a duty described above on prospective domain name registrants to search global trademark databases, to avoid any marks found therein, even if the mark was selected out of the dictionary, and to infer bad faith on the part of a respondent who registered such a dictionary word domain name. Such was the position of the Panelist back in 2014, in a dissent to the majority’s denial of the complaint in bespoke.com. Andrew Allemann discussed the decision here.

The key reasoning in the dissent:

“The Dissenting Panelist disagrees with the majority of the Panel. Given the international registration of the Complainant’s trademark, a simple search on the WIPO Global Brand Database would have sufficed to reveal it.”

is then followed by the inference that there could be no legitimate way to offer bespoke.com for sale, on the assumption that the only possible value in such a dictionary-word domain name came from the use made by the little-known Complainant –

… The Dissenting Panelist finds that the Respondent’s only interest in buying the disputed domain name was to sell it for valuable consideration in excess of its out-of-pocket expenses, either to the trademark’s competitors, or to the trademark owner.

Such was the position of the Panelist in the SiteAnalytics.com decision, issued in March of last year, in which the Panelist acknowledged that the domain name might have been registered by the Respondent without any knowledge of the Complainant, but nevertheless imposed an affirmative duty on the Respondent to search for and to avoid any domain names that may be confusingly similar to marks which might be used in a trademark sense, even if such a mark is unregistered and descriptive, as was the case in the SiteAnalytics.com dispute:

“Complainant is not well-know, so it’s entirely possible that the Respondent doesn’t know the SITE ANALYTICS trademark. However, Respondent might have discovered said trademark if it had conducted a trademark or other search before registering the Disputed Domain Name. The Panel is of the opinion that it was Respondent duty to search proactively in order to avoid infringing third party rights.”

Zak Muscovitch, in his comment on the decision, suggests that there was insufficient evidence to support that the Complainant had any enforceable rights at all in the unregistered mark for the evidence presented fell far short of the standard required to demonstrate secondary meaning in such a descriptive term. Indeed, as Muscovitch states:

“had the Respondent conducted a US trademark search it would have found that SITE ANALYTICS was refused registration when it was applied for by a third party due to being considered merely descriptive in relation to the applicant’s services.”

Further, conducting an online search of “site analytics” would have brought up numerous third-party uses of the phrase in its descriptive sense. As Muscovitch concluded:

“So, it seems that it was the Panelist that should have undertaken a search rather than requiring one of the Respondent.”

This Panelist imposes on a Respondent, a “duty to search proactively in order to avoid infringing third party rights.” The Panelist considered the violation of this self-imposed standard of conduct to be bad faith justifying the transfer of the bespoke.com domain name, which the Respondent had acquired for over $18,000 at a public auction, and the transfer of a domain name based on the descriptive term “site analytics”, which was not even a registered trademark.

This raises the question as to what are the standards of conduct on a Complainant before filing a Complaint, especially one that is legally represented? If those standards of conduct are violated, is it appropriate to draw the inference that the Complainant is abusing the UDRP?

Should a legally represented Complainant be held to a standard that it understands the UDRP and is aware of well settled jurisprudence?

Should a legally represented Complainant be held to a standard that it conducts minimal due diligence to verify its allegations?

Should a legally represented Complainant, when presented with compelling evidence that demonstrates the falsity of its allegations, withdraw its complaint? Or if it does not take the affirmative step of withdrawing, should it at least not persist with burdening and harassing the Respondent by continuing to assert its spurious allegations?

If these are indeed the standards of conduct expected of a legally represented Complainant, in the <GPI .com> dispute the Complainant breached them all.

The Complainant relied on the long-discredited theory of Retroactive Bad Faith:

“the transfer of a domain name to a third-party amounts to a new registration and that successive renewals of a domain name constitute re-registrations.”

The Complainant presented no evidence of bad faith registration or use, the cornerstone of the UDRP. As the Respondent accurately stated:

“Non-use or passive holding of a domain name alone does not constitute bad faith.”

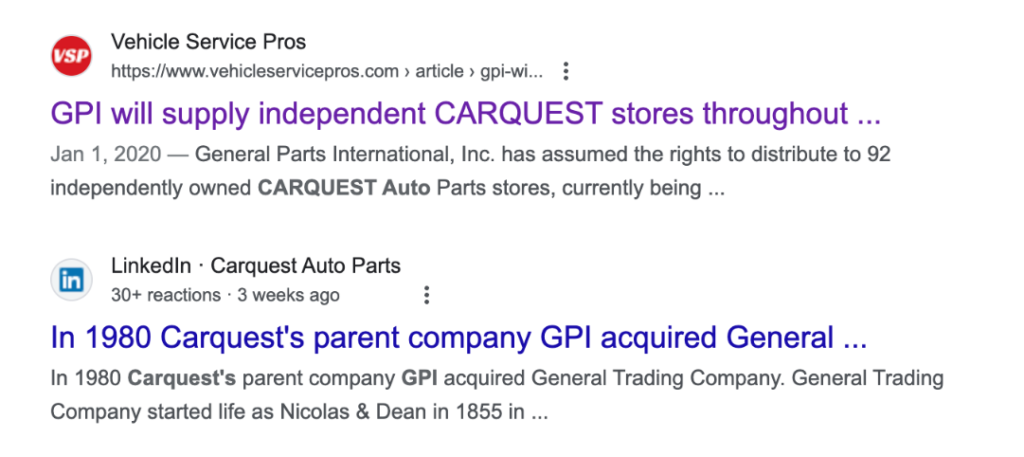

Although the Complainant states: “However, an Internet search of the GPI acronym does not yield any search results related to Respondent or its affiliates”, the Complainant apparently failed to conduct a Google search on “GPI” and “Carquest” (the name of the Respondent). If it had done so it would have immediately found compelling evidence of the Respondent’s legitimate interest in “GPI”:

The Complainant, after the Respondent submitted its Response providing evidence of its long history in connection with the commercial use of GPI and its continued legitimate uses of the <GPI .com> domain name, persisted with its baseless accusation by making an Additional Submission. In its Additional Submission it demonstrated a failure to understand a core element of the Policy – for it acknowledged that the Respondent had made a legitimate use of the domain name prior to the filing of the Complaint, which is a sufficient defense under the Policy, but merely argued that the domain name was no longer actively being used.

RDNH is a finding made at the sole discretion of the Panel. There is little clear guidance provided under the Policy as to the circumstances where an RDNH finding is warranted. Yet as there have now been over 500 RDNH findings, there is a growing consensus and an increasingly robust jurisprudence as to which circumstances justify a finding of RDNH. The RDNH.com website publishes a table listing decisions where a finding of RDNH was made along with the reasons offered by the respective panels for making the RDNH finding. There are many different rationales offered, the most frequent of which include:

- Disregarded Precedent

- Legitimate Interest – Complainant Knew

- Bad Faith – No Evidence

- Unsupported Allegations

- Harassment

Especially in conjunction with being Represented by Counsel.

Sometimes a Panel will list one or two such reasons as sufficient justification for a finding of RDNH. Here in the <GPI .com> dispute all six of the above circumstances are present. Yet no RDNH finding was made.

In <GPI .com> the main reason given for failing to make of finding of RDNH is:

“However, Panel finds that it was not possible for the Complainant to ascertain if and how the Respondent was in fact using the disputed domain name in the absence of a public facing use such as publicly accessible website.”

The same Panelist who imposes a duty on respondents to search for commercial uses of dictionary words and three-letter acronyms and who considers it bad faith to speculatively register domain names based on dictionary words or three-letter acronyms or other non-distinctive terms if any such commercial use exists, does not impose a duty on a Complainant to conduct an obvious Google search on the Respondent’s name and the asserted mark before launching a baseless Complainant.

The Panelist seems to hold that an absence of a clear, present legitimate interest is sufficient justification for launching the Complaint. Yet the Complainant launched a Complaint that disregarded the requirements set forth under the Policy that must be met in a successful complaint, that asserted long-discredited interpretations of the Policy while failing to conduct the most basic investigation of the facts it alleges, and that asserted speculative allegations unsupported by evidence, all in a willful attempt to seize a highly valuable three-letter dot-com domain name without compensating the owner.

What are the standards of conduct on Respondents under the UDRP? What are the standards of conduct on Complainants under the UDRP? The standards of conduct expected of Respondents and of Complainants in the disputes discussed here appear to be disproportionate.

Respondent fails “Oki Data” test but prevails on bad faith

Thor Tech Inc. v. Eric Kline, WIPO Case No. D2023-4275

<airstreammarketplace .com>

Panelist: Mr. Bradley A. Slutsky (replaced Mr. Richard G. Lyon), Mr. W. Scott Blackmer, and Lawrence K. Nodine (Presiding)

Brief Facts: The Complainant (with its affiliated operating companies) is the world’s largest manufacturer of recreational vehicles, including AIRSTREAM vehicles. The Complainant uses its AIRSTREAM trademark on RV travel trailers (first used in 1932) and a wide variety of related goods and services, including clothing, camping equipment, and accessories. The Complainant owns many registrations for the Mark, including U.S. trademark registrations (earliest registered on June 14, 1955). The Respondent describes himself as an AIRSTREAM enthusiast whose family travelled in an AIRSTREAM RV trailer when the Respondent was a child. As an adult, the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name on October 21, 2019, to help people buy and sell used AIRSTREAM vehicles. In February 2022, before the Respondent received any communications from the Complainant, the Respondent added the statement “[b]uilt by enthusiasts, for enthusiasts” to the first page of the Website. The Respondent’s sworn statement declares that the Website associated with the disputed Domain Name facilitates the sale of AIRSTREAM vehicles only. The Website has had 2.5 million unique visitors…; has more than 18,000 user accounts…; and it has facilitated the sale of about 4,480 AIRSTREAM.

The Complainant anticipated, correctly, that the Respondent would rely on the nominative fair use defense. For several reasons, the Complainant contends that the Respondent has not satisfied the illustrative fair use criteria as generally articulated in Oki Data Americas, Inc. v. ASD, Inc., WIPO Case No. D2001-0903 and cannot claim rights and legitimate interests in the Domain Name. The Respondent contends that he has rights and legitimate interest in the disputed Domain Name under nominative fair use principles and that he has satisfied the Oki Data criteria. He argues that the links to third parties do not lead to Complainant’s competitors, but rather to vendors that offer AIRSTREAM accessories or services, or generic services to the RV community and that the copying of content derived from the Complainant was not significant, and, in any event, was deleted in response to the Complainant’s protests. Moreover, he added a sufficient disclaimer after receiving the Complainant’s letter in November 2022 and that he improved the positioning of the disclaimer by moving it from the bottom to the top of the landing page, albeit after the Complaint was filed in this proceeding.

Held: The Complainant contends that the Respondent’s use infringes its trademark and therefore cannot be considered bona fide, stating: “It is well settled under the Policy that a knowingly infringing use of a trademark to offer goods and services is not a bona fide offering of goods and services under the Policy.” (U-Haul International, Inc. v. PrivacyProtect.org / Ken Gossett, WIPO Case No. D2011-0347). The Panel rejects this contention on the facts presented in this proceeding because the outcome of this dispute in a United States court is right now based on speculation. Consequently, The Panel cannot conclude that the Respondent knowingly “infringed” Complainant’s trademark. This case illustrates why panels interpreting the Policy consistently decline to rule on claims of “infringement.” UDRP disputes are abbreviated proceedings that are not meant to resolve disputes that turn on facts that are in dispute or on legal principles that vary by jurisdiction. The Panel finds that it is appropriate to apply the Oki Data principles to evaluate whether, under UDRP jurisprudence, the Respondent has rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

It is apparent to the Panel that the Respondent intended to offer a bona fide service in good faith, but that he failed to implement safeguards sufficient to prevent the potential for Internet users mistakenly to perceive affiliation with the Complainant. For these reasons, the Panel finds that while it has come close and made apparent corrective efforts, the Respondent has not fully satisfied Oki Data. The Panel emphasizes that this is a close call. Although the term “marketplace” does not, in the Panel’s view, explicitly suggest affiliation, neither does it negate affiliation, and the landing page disclaimer is not prominent enough. This is not sufficient to satisfy Oki Data’s requirement that the Respondent “accurately disclose Respondent’s relationship with the Mark owner.” Even though the Respondent failed to clarify its relationship with the Complainant as required by Oki Data, the Panel is not persuaded that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith. Panelists frequently observe that the UDRP is meant to address intentional bad-faith conduct and not “ordinary” trademark infringement. This case illustrates the distinction. Although the Complainant may have a credible claim of trademark infringement, it has not proved that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith within the meaning of the Policy.

The Panel finds it more likely that Respondent began in good faith but without a thorough understanding of his obligations to stay on the right side of a fair use assessment. Although the Panel has found that Respondent’s inclusion of the phrase “[b]uilt by enthusiasts for enthusiasts” was not by itself sufficient to negate implied affiliation, it is evidence of good faith. The Panel also notes with approval that the Respondent responded to the Complainant’s complaint letters by making adjustments intended to address the Complainant’s concerns. The Panel also finds insufficient Complainant’s reliance on the Respondent’s use of material copied or derived from the Complainant’s copyright works. These infractions, most of which the Respondent corrected in response to the Complainant’s protests, are not quantitatively enough to support a finding that Respondent “intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users by creating a likelihood of confusion with the complainant’s mark.” It is equally likely that Respondent only sought to offer Internet visitors the information in the articles without any intention to exploit any suggestion of affiliation.

This is a case where more information, as well as the interpretation of the Lanham Act in the particular jurisdiction where any dispute would be resolved, could be determinative. On the abbreviated record available in a UDRP proceeding and with no discovery, the Panel can only determine that the information available at this point neither rises to the level necessary under the Policy to show rights or legitimate interests nor rises to the level necessary under the Policy to show bad faith.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Dinsmore & Shohl LLP, United States

Respondents’ Counsel: Lewis & Lin, LLC, United States

Editor: We are saddened to learn about the passing of the honourable Panelist, Richard G. Lyon, referenced in this case. See this DNW.com article for more.

Case Commentary By Igor Motsnyi:

Igor is an IP consultant and partner at Motsnyi Legal, www.motsnyi.com , “Linkedin”. His practice is focused on international trademark matters and domain names, including ccTLDs disputes and the UDRP. Igor is a UDRP panelist with the Czech Arbitration Court (CAC) and the ADNDRC, and is a URS examiner at MFSD, Milan, Italy.

The views expressed herein are Igor’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the ICA or its Editors. Igor is not affiliated with the ICA.

In <airstreammarketplace. com> the Panel admitted that Respondent was close to demonstrating his legitimate interest under “Oki Data” but failed to do. However, this was not the end of the story as the Panel concluded that Respondent did not act in bad faith. This decision, in my view, deals with two interesting aspects of UDRP jurisprudence:

1. Failure to establish legitimate interest does not always indicate respondent’s bad faith.

WIPO Overview 3.0 notes on the relation between the 2d and the 3d UDRP elements: “In some cases therefore, panels assess the second and third UDRP elements together, for example where clear indicia of bad faith suggest there cannot be any respondent rights or legitimate interests” (see sec. 2.15). This applies to obvious cases of cybersquatting. However, some cases are not so simple, in particular “Oki Data” cases and cases that involve free speech and criticism. The Panel in <airstreammarketplace. com> concluded that Respondent acted in good faith but “without a thorough understanding of his obligations”. This was, in Panel’s view, insufficient to find bad faith.

This 3-member Panel decision demonstrates that failure to pass a test under the second element does not always mean Respondent’s bad faith.

I would recall “Dover Downs Gaming & Entertainment, Inc. v. Domains By Proxy, LLC / Harold Carter Jr, Purlin Pal LLC”, Case No. D2019-0633 (“Dover Downs”), one of the leading WIPO decisions on the “impersonation test” in free speech and criticism UDRP cases. While supporting the application of the impersonation test, the Dover Downs Panelist noted the following on the 3d UDRP element: “The Panel’s finding under the impersonation test does not itself prove bad faith; all that the impersonation test shows is that Respondent had no rights or legitimate interests in the Disputed Domain Name. Complainant must still come forward with evidence to show that Respondent registered and used the Disputed Domain Name in bad faith”.

Following the same logic, the Panel in <airstreammarketplace. com> separated the “impersonation” issue (“Respondent arguably did not take sufficient care to negate implied affiliation”) from the bad faith issue.

Therefore, while in some situations, absence of rights or legitimate interest may indicate bad faith, in the other more nuanced cases, the third UDRP element requires separate analysis and consideration. Looking at the totality of circumstances can be helpful.

2. Limitations of the Policy and its “minimalist” character

The Panel in <airstreammarketplace. com> emphasized limitations of the UDRP citing ICANN “Second Staff Report on Implementation Documents for the Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy”, par. 4.1.c., in the footnote of the decision.

The Panel recognized that while Complainant “may have a credible claim of trademark infringement, it has not proved that Respondent registered the Disputed Domain Name in bad faith within the meaning of the Policy”.

This is a worthy reminder to both parties and panelists.

Indeed, the UDRP is a great tool to resolve some domain name disputes and its popularity is understandable.

However, the Policy was not designed to deal with all domain name disputes.

This limitation was reflected in the legislative history of the Policy and remains a feature of the UDRP.

Uninterrupted Chain of Ownership Precedes Complainant’s Trademark

Ziip Inc v. Hagop Doumanian, WIPO Case No. D2023-5217

<ziip .com>

Panelist: Ms. Ingrīda Kariņa-Bērziņa

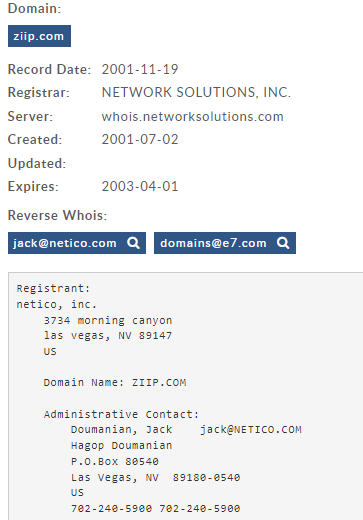

Brief Facts: The US-based Complainant markets app-connected electrical devices for esthetic facial treatments under the ZIIP mark. The Complainant is the proprietor of the US trademark for ZIIP (word mark), registered on August 11, 2015 (claiming first use, April 29, 2015). The Complainant claims that it has invested USD $3,500,000 in the development and marketing of its ZIIP brand which has acquired widespread recognition. The disputed Domain Name was registered on April 1, 2000. The Respondent is in the business of registering generic, descriptive, misspelling of common words, and acronym domain names. The evidence in the record indicates that, as of 2003, the registrant was identified as “Jack Doumain” or “J.D”. The Respondent in these proceedings is a party named “Hagop Doumanian”. The record reflects that an update to the Whois information was recorded on March 1, 2023, which the Complainant claims as the date of registration of the Domain Name.

At the time of the Complaint, the disputed Domain Name resolved to a website featuring pay-per-click (“PPC”) links for “app software”, “open zip application”, and “roller banner”. On the same web page, the disputed Domain Name was offered for sale for USD $68,000. The record shows that the Respondent is a professional domainer in the business of acquiring and selling short domain names. The Complainant alleges that the website features PPC links tangentially related to the Complainant’s business, thereby generating revenue for the Respondent based on the Complainant’s investment in its e-commerce brand and that the disputed Domain Name redirects to a website on which it is offered for sale for USD $68,000, an amount that significantly exceeds the costs of registering it.

The Respondent challenges the Complainant’s ownership of the ZIIP trademark registration, stating that the registration identifies the owner as Ziip, LLC, with an address in Wyoming, whereas the Complainant is identified as Ziip, Inc., with an address in California. The Respondent further contends that historical records from November 2015 indicate that an organization called Netico, Inc., using the same email as the Respondent, was the registrant of the disputed Domain Name as of the year 2003. Netico, Inc. was a company established in 2000, dissolved in 2021 and re-established in 2022. The Respondent was the President of this company from its formation. The disputed Domain Name has been used to redirect to third-party marketplace websites since 2012 when it was first listed for sale.

Held: In this case, the Complainant’s trademark rights have been established as of August 11, 2015, the date of registration of the trademark. The disputed Domain Name was registered on April 1, 2000. The Complainant has not provided evidence of its use of the ZIIP mark as of that date. Rather, the Complainant asserts that the actual registration of the disputed Domain Name took place on March 1, 2023, when the Whois record for the disputed Domain Name was updated. The Panel notes that the evidence in the record on this point is unsatisfactory. The Panel notes the Complainant, which bears the burden of proof in a UDRP proceeding, has failed to provide any evidence, such as any entries from historic WhoIs records for the disputed Domain Name that might have pointed to a registrant transfer in 2023, or any evidence that the Respondent at any point targeted the Complainant.

The Respondent argues it registered the disputed Domain Name in 2000 as part of its longstanding business of registering short domain names. The Panel finds that the evidence provided by the Respondent itself indicates that, on the balance of probabilities, the disputed Domain Name has at all times been controlled by it, albeit under different corporate identities. The Respondent also provides evidence that the disputed Domain Name was made available for sale in 2012 and 2013, predating the Complainant’s establishment of trademark rights. Moreover, there is no evidence that the Respondent at any time attempted to sell the disputed Domain Name to the Complainant. The use of the disputed Domain Name for PPC links, under the circumstances, does not support a finding that the Respondent is attempting to capitalize on the value of the Complainant’s mark.

Generally speaking, panels have found that the practice as such of registering a domain name for subsequent resale (including for a profit) would not by itself support a claim that the respondent registered the domain name in bad faith with the primary purpose of selling it to a trademark owner (or its competitor). The evidence in the case file, as presented, does not indicate that the Respondent’s aim in registering the disputed Domain Name was to profit from or exploit the Complainant’s trademark. Rather, on balance, the evidence indicates that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name for its value as a short domain name related to a common English word. While overall the evidence presented by both Parties is incomplete, it is on the Complainant to make out its case and the Panel does not find sufficient evidence that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith targeting the Complainant or its trademark rights.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Justec Legal Advisory Services LLC, United States

Respondents’ Counsel: Cylaw Solutions, India

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

Congratulations to the Digest’s Editor-in-Chief, Ankur Raheja of Cylaw Solutions for successfully representing the Respondent in this case.

This case is noteworthy because the Panelist correctly found that notwithstanding nominal changes in the historical registration records, “the disputed domain name has at all time been controlled by [the Respondent”]. It is important to recall, as the Panelist apparently did in this case, that it is well settled that where an unbroken chain of underlying ownership is established, a change in the recorded Whois details will not be considered a new registration for the purposes of the UDRP (See for example, Angelica Fuentes Téllez v. Domains by Proxy, LLC / Angela Brink, WIPO Case No. D2014-1860, and also see; Google Inc. v. Blue Arctic, NAF Claim Number: FA1206001447355), and also see WIPO Consensus View 3.0 at Paragraph 3.9: “Where Respondent provides satisfactory evidence of an unbroken chain of possession, panels typically would not treat merely “formal” changes or updates to registrant contact information as a new registration.”).

This case is also interesting as it relates to the issue of when RDNH should be considered. RDNH was not expressly considered in this case. In last week’s Digest, I discussed the <Innnoviti .com .co> matter, wherein RDNH was found despite there being no response. That case demonstrated that a Panelist is obliged under Rule 15(e) to consider RDNH where warranted, even if it is not requested by a party. In this particular case, should RDNH have been expressly considered by the Panel whether or not it was requested in this case? (and I understand that it was).

The Complainant did not apparently review historical Whois records when preparing the Complaint. Had the Complainant reviewed them, it may have realized before filing the Complaint that there appears to be a possible connection between the current Respondent and the historical registrants. A quick DomainTools search shows that in the first archived historical Whois record, the Admin contact is “Jack Doumanian”. Doumanian is of course, the surname of the current respondent. Obviously that is not a coincidence, and from this easily discernible fact alone, the Complainant could have determined that the Respondent’s rights appear to have predated its own more recent trademark.

The question then is (as discussed above by Nat Cohen in the GPI case), what obligations of due diligence and investigation does a Complainant have before launching a UDRP proceeding? Are Complainants required to conduct historical Whois searches or other investigations before certifying a Complaint as complete and accurate? In this case, if there were such an obligation then it would possibly be an abusive complaint as a result of failing to conduct such searches.

What about how the Complainant’s assertion that “the actual registration of the disputed domain name took place on March 1, 2023, when the Whois record for the disputed domain name was updated, [implying] that the update indicates that a change of ownership has occurred and a new registration, post-dating its establishment of trademark rights, has been effected”? As the Panel noted, the Complainant failed to provide any evidence of a 2023 transfer, so ostensibly made a blind allegation against the Respondent when it was within the Complainant’s control to investigate and review historical Whois records. Indeed, the Panelist noted that it is “Complainant who bears the burden of proof in a UDRP proceeding [and] has failed to provide any evidence such as any entries from historical Whois records…that might have pointed to a registrant transfer in 2023”. As noted by the three-member Panel in Watchdog USA, LLC v. Newfold Digital, Inc., FA2307002052775 (Forum Aug. 18, 2023), an RDNH finding “is justified where a complainant proceeds despite the fact that it knew or should have known that it did not have a colourable claim under the Policy” [emphasis added]. Should the Complainant to have known?

In my view, it was properly within the scope of the Panelist’s reasonable discretion to not find RDNH in this case because the question of a Complainant’s obligations under the Policy and pursuant to its certification, are arguably not yet unequivocally answered by the case law. Nevertheless, perhaps the Panelist should have at least acknowledged that an RDNH request was made and set out the Panelist’s rationale for not declaring it.

Panelist Dismisses, But Leaves Door Open for Refiled Complaint

Silver Point Capital, L.P. v. Elisha Finman, NAF Claim Number: FA2401002079392

<silverpointequity .com> and <silverpointequities .com>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a prominent SEC-registered investment adviser founded in 2002. The Complainant asserts rights in the SILVER POINT mark based upon registration with the USPTO (registered on January 19, 2010). The Respondent is an individual who runs a small, family-run real estate investment company that trades under the name Silver Point Equity. The Respondent’s business is located in Atlantic Beach, New York and the local beach is known as Silver Point, which is where the Respondent’s business takes its name from. The Respondent uses the Silver Point Equity business name for its business, online marketing, LinkedIn, social media and as part of its e-mail. The Respondent has an active website at the <silverpointequity .com> domain name that promotes its real investment services.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is passing off as the Complainant in order to conduct a phishing scheme as it is publishing a website under a virtually identical name and purporting to offer real estate investing services (which the Complainant also offers). The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent is confusing customers as to the source of its investment services for commercial gain. The Respondent denies that it is engaged in any form of scam and notes that there are numerous other businesses in the real estate and finance industries that use the Silver Point name, indicating that the Complainant does not have an exclusive right to or reputation in the SILVER POINT name.

The Complainant via additional submissions, alleges that after the Complaint was filed, the Respondent offered to sell the Domain Names to the Complainant for a significant sum. The Respondent responds that on February 6, 2024, the Complainant’s representative called the Respondent, and asked for the Respondent to name an asking price. The Respondent named an asking price, by reference to the value of a deal he was working on which could be impacted by the loss of the Domain Names. The Complainant’s representative said that this was a larger number than they were expecting and he would present it to his client.

Held: The Panel holds that the Complainant has not made out a prima facie case. Rather, there are factual and legal issues that are unresolved by the evidence presented and the Panel believes that this case is not well suited for resolution under the Policy. The Complainant, in its Complaint, submits that the Domain Names are used as part of a phishing scheme to mislead members of the public. This submission is not supported by the evidence before the Panel. Furthermore, the evidence of the settlement conversation held between the Complainant’s representative and the Respondent’s representative is not determinative of whether the Respondent has rights or legitimate interests; the Complainant’s representative sought a settlement offer and the Respondent provided one which was not accepted by the Complainant; by itself, this does not establish the Respondent’s use of the Domain Names as not being bona fide.

The Domain Names resolve to a website, operated by the Respondent which, on its face, indicates that the Respondent operates a real estate investment firm known as “Silver Point Equity”. The Respondent’s website does not either explicitly or implicitly make any reference to the Complainant or otherwise suggest an affiliation. Moreover, the Respondent has provided a clear reason for the use of the Silver Point term (namely that it refers to a geographical feature where the Respondent is located) and exhibits limited collateral demonstrating the use of the Silver Point name and Domain Names for his business (Linkedin page, Respondent’s Website, and e-mail address). The Panel also notes that there is no other evidence of any conduct engaged in by the Respondent that suggests the use of the Domain Names is anything other than for a bona fide offering of services, such as phishing e-mails, misleading statements, a pattern of conduct of abusive registrations or the like.

The Panel acknowledges that the Respondent’s conduct may infringe Complainant’s SILVER POINT mark or amount to passing off. However, the question of trademark infringement is beyond the scope of the present proceeding, which is summary in nature and hence the limited evidence that the Respondent operates a real estate investment business known as Silver Point Equity is a sufficient basis to find that the Complainant has failed to demonstrate that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name. The Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy is designed to deal with clear cases of cybersquatting. If the Complainant wishes to bring proceedings against the Respondent for trademark infringement or passing off such a proceeding is more appropriately brought in a court of competent jurisdiction. The Panel notes that if further information arises that suggests that the motives of the Respondent in registering the Domain Names were anything other than the intention to use in respect of his Silver Point Equity firm, there may be grounds to consider a refiled complaint, subject to the applicable criteria.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Scott Kareff of Schulte Roth & Zabel LLP, New York, USA.

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: The Panel in this case reached the correct conclusion about the suitability of this case for the UDRP. While expressly acknowledging that “the Respondent’s conduct may infringe Complainant’s SILVER POINT mark or amount to passing off” the Panelist adroitly noted that “the question of trademark infringement is beyond the scope of the present proceeding, which is summary in nature” and therefore despite the limited evidence of Respondent’s business, it was nonetheless enough to push this case out of the UDRP since it was not a “clear case of cybersquatting”.

Last week I mentioned the “yard stick” by which Panelists should judge whether a Respondent’s possibly infringing business is “bona fide”, i.e. ‘whether the respondent’s use is real or pretextual’. In the present case, there was little evidence of use by the Respondent for his business, but as the Panel noted, it was nonetheless sufficient given the limited nature of the UDRP procedure. Perhaps in a more robust forum such as a court, the Complainant will be able to demonstrate that the Respondent’s use is pretextual, but the Complainant could not prove that with its Complaint. That is why the Panelist prudently left the door open for a refiled Complaint if additional evidence were to be discovered.

Respondent Attempts to Pass Off as Complainant

Stormtech Performance Apparel Ltd. v. 超罗, CIIDRC Case No. 22088- UDRP

<stormtechshop .com>

Panelist: Mr. James Plotkin, Q.Arb

Brief Facts: The Complainant, incorporated on February 8, 1968, designs and manufactures sporting and outdoor apparel. The Complainant has its operations span Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union. It also distributes products to other countries, including Australia, New Zealand and Mexico. The Complainant operates its business, in part, through various domain names, for example: <stormtech .ca> (December 5, 2000); and <stormtechusa .com> (February 12, 2003). Each of these websites hosted at these Domain Names contains copyrighted texts, images, and graphics and also contains depictions of the Complainant’s trademarks. The Complainant provided evidence showing these marks are registered in various jurisdictions, including Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Mexico, Australia, China and Japan. The earliest of these registrations is a Canadian registration for word mark STORM TECH registered on March 18, 1994.

The disputed Domain Name was registered on August 8, 2022. The Complainant provides screen captures that appear to depict content and apparel it sells on its websites. According to the Complainant, the content hosted at the disputed Domain Name changed on or about November 19 or 20, 2023. In that regard, the Complainant submitted timestamped screenshots showing what appear to be pages offering for sale various sporting glasses, goggles, helmets and related apparel from a company other than the Complainant. The Complainant alleges that using a disputed Domain Name for illegal activity, such as passing off and counterfeiting has consistently been held to demonstrate a lack of legitimate interest in a disputed Domain Name and bad faith. Until recently, the disputed Domain Name hosted an apparent fraudulent storefront impersonating the Complainant’s legitimate websites without authorization. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: Given the Respondent’s website’s content, and the failure to file a response explaining it, the Panel is satisfied the Complainant has shown that the Respondent lacks a legitimate interest in the Domain Name on a prima facie standard. In that regard, based on the additional evidence the Complainant submitted (the witness statement), the Panel is satisfied that the screenshots the Complainant provided are in fact of the website content hosted at the disputed Domain Name. It bears mentioning that, in the Panel’s view, the bare screenshots with no timestamp or URL information initially submitted would not have been sufficient evidence. This is because they offered no means of determining the provenance of those screenshots. However, the Complainant has bettered its evidence, which the Panel now considers sufficient given the nature of these proceedings.

With respect to UDRP paragraph 4(b)(iii), it appears the Respondent was using the Domain Name to compete with the Complainant. In any event, it is clear from the Respondent’s website’s content that, at a minimum, that the Respondent intended to disrupt the Complainant’s business and divert traffic away from the Complainant’s websites. This demonstrates bad faith use and registration. With respect to UDRP paragraph 4(b)(iv), the Panel agrees the Respondent’s conduct demonstrates an intention to attract Internet users to the website hosted at the disputed Domain Name for commercial gain. The website’s content lays bare the Respondent’s attempt to create a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or endorsement of the Respondent’s website. In light of the foregoing, the Complainant has established that the disputed Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Mr. Rachel E. Schechter (Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP)

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

The Brandable Idea

The Brandable Idea